Rural South Carolina Town Pays Tribute to Hometown Hero, Motown’s James Jamerson

EDISTO ISLAND, S.C. — The flier at first appeared a bit incongruous on the small bulletin board near the faded wooden steps leading up to McConkey’s Jungle Shack.

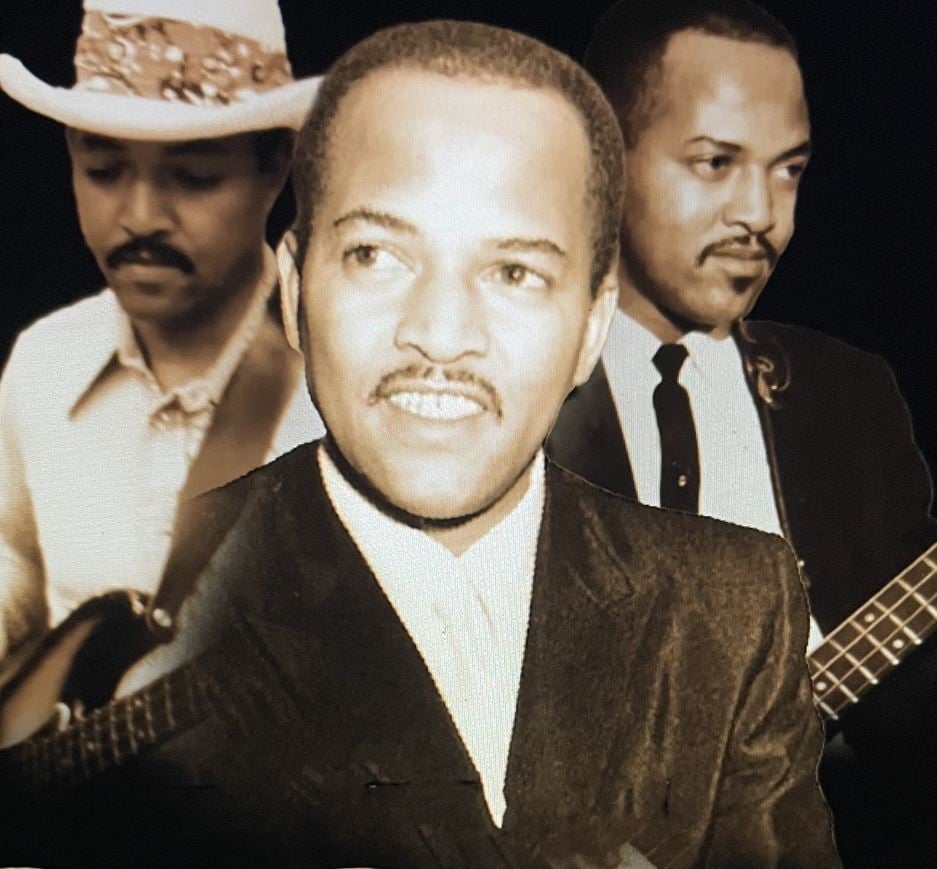

There, next to a list of specials of shrimp and chips, clam strips and hot hush puppies at this casual beachside establishment, was the smiling face of James Jamerson, the legendary bass guitarist who made his mark by playing on almost all of Motown’s greatest hits in the 1960s and early ‘70s.

To those in the know, Jamerson, together with a succession of drummers, including William “Benny” Benjamin, Richard “Pistol” Allen, and Uriel Jones, was the purveyor of the unmistakable groove that propelled groups like Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, The Supremes, The Four Tops, The Temptations and legions of others to the top of the charts.

The “Da-Dum-Dum, Da-Dum-Dum” you hear at the beginning of the Temp’s “My Girl,” that’s Jamerson, and it’s Jamerson again providing the raging bass riffs thumbing into the chorus of “Reach Out I’ll Be There” by the Four Tops.

You name the Motown classic: “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough,” “Baby Love,” “Uptight (Everything is Alright),” or “Sugar Pie Honey Bunch,” and what you’re hearing is Jamerson weaving a succession of bass notes into gold.

In fact, early on in Motown Records’ history, it’s said label founder Berry Gordy, Jr., would not start a session until he knew Benjamin and Jamerson, the core of the band later known as the Funk Brothers, were in the studio and ready to begin.

But why call attention to Jamerson, who died in Los Angeles 40 years ago, here, on this sea island some 40 miles south of Charleston, deep in South Carolina’s lowcountry?

Eyeing the flier at McConkey’s more closely, the answer is quickly evident. Jamerson, it turned out, was born in Edisto in January 1936, and evidently lived there long enough to be considered a member of its New 1st Missionary Baptist Church.

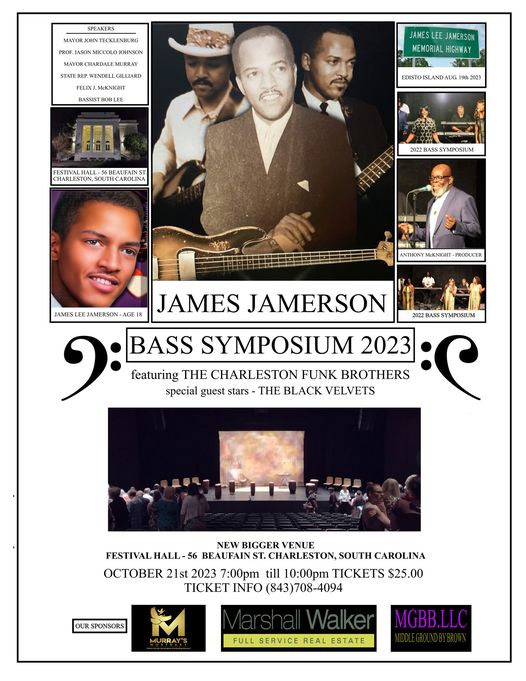

The simple poster was an announcement of a Jamerson tribute concert at the Edisto Beach Civic Center, which it promised would be a dynamic stage show consisting of a live band — the “Charleston Funk Brothers” — and local singers and dancers filling in for the Motown greats.

The concert, held at the modest Edisto Beach Civic Center, was a sell-out.

But further investigation revealed that wasn’t all that was happening on Edisto Island regarding the musician who can now rightfully be called a favorite son.

A few days earlier, the state designated the intersection of S.C. Highway 174 and Steamboat Landing Road, a significant crossroad in the small community “James Lee Jamerson Memorial Highway.” As a child the future bass player lived just 2,500 feet or so north of the new street sign’s location.

For Anthony McKnight, a Charleston resident and Jamerson’s first cousin, the two events, with which he was intimately involved, were a highpoint in his often frustrating 23-year quest to get South Carolina to recognize his family member as an important, history-making native of the state.

“All of a sudden, everybody seems to love James Jamerson,” McKnight observed the other day during a conversation with The Well News.

“Except the people who run the South Carolina Hall of Fame,” he said.

Though anyone meeting McKnight would find it hard to ever imagine a man with his broad smile and easy-going manner getting angry, the hall has long been a sore-spot for him.

Designated the state’s “official” Hall of Fame by former Gov. Jim Hodges in September 2001, the nonprofit, which operates under a state charter, is supposed to “recognize and honor both contemporary and past citizens who have made outstanding contributions to South Carolina’s heritage and progress.”

According to its website, “one contemporary and one deceased citizen may be inducted into the Hall of Fame annually” and it goes on to say “persons born in South Carolina who obtained recognition elsewhere and persons born elsewhere but who made their home in and obtained esteem and recognition in the state of South Carolina are eligible for induction.”

Musicians are certainly represented among its honorees, the most recent inductee being Darius Rucker — Hootie of Hootie and the Blowfish — who was elected to the hall of fame in 2020.

Another is John Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie, who was born in Cheraw, South Carolina, and who gained worldwide fame as one of the pioneers of bebop in jazz music.

But time and again, McKnight said, Jamerson has been passed up either by the Confederation of South Carolina Local Historical Societies, which selects the nominees, or the hall’s board of trustees, which approves those it deems worthy.

“What they tell me is he doesn’t have the votes,” he said, before clamping down on what one suspects are the few choice words he’d like to add.

James Jamerson was the son of James Jamerson, Sr., who worked in Charleston’s shipyards, and Elizabeth Bacon, a domestic worker. He was the second of their two boys, the older son being named Richard.

Life for the young family was hard and tumultuous and they divorced before their youngest son had started school.

It wasn’t long after that Elizabeth Bacon decided to move to Detroit and start a new life. While she was getting herself established in the city, she left her boys in the care of her sister, McKnight’s mother, Everlina McKnight.

By the time Anthony McKnight was born, Jamerson had grown into a teenager and would soon leave to join his mother in the Motor City.

In the intervening years, however, Jamerson had developed a passion for music, finding encouragement both from his aunt, who sang in the church choir, and his grandmother, Martha Brown, who played piano.

By the time he reached the upper grades in elementary school, Jamerson himself was performing in public on the piano and briefly played the trombone.

In the meantime, he filled out his musical education by listening to the blues, gospel and jazz played by the local radio stations.

Jamerson joined his mother in Detroit in 1954. Now a high school student, most who met him then commented on how reserved the young man could be; However, it’s likely that what appeared to be standoffishness, was really just absorption in a new musical passion — the stand-up bass.

It wasn’t long before he was recognized in and out of school as an excellent bass player, appearing in clubs and getting work as a sideman in the city’s recording studios.

His real future didn’t fall into place until five years after his arrival. It was then that Berry Gordy plunked down what amounted to his life savings and purchased 2648 West Grand Boulevard in Detroit, the residential property he’d soon convert into “Hitsville USA” as the large blue letters on its white facade declared.

Jamerson would work for the company for the next 14 years, a period when Motown defined an era and boldly and rightly laid claim to the title “the sound of young America.”

“It was a situation that was pretty typical in the old days,” McKnight said. “If you couldn’t find good, stable work in the South, you migrated north, in many cases, like my aunt, you migrated to Detroit.

“And of course, because she left looking for work, there was no way she could take Richard and James initially. So she left them with my mom until she got steady [work], and once she got steady, she sent for Richard and James and history was made,” he said.

McKnight doesn’t have a lot of distinct memories of Jamerson from his childhood due to marked differences in their ages, but he did recall an early indication of how serious his cousin was about music.

According to the story, probably repeated to McKnight by his mother, Jamerson was asked to write a paper in the third grade describing what he wanted to be when he grew up.

Jamerson responded with a paper in which he stated for the first time to anyone that he wanted to be a musician like the ones he heard on the radio.

“The teacher only gave him a B on the paper and said something about the life of a musician being impractical or something like that, and I think from that point forward he was determined to prove that teacher and anyone that doubted him wrong,” McKnight said.

If memories of their shared time in the Lowcountry are scant, McKnight has a wealth of them from his junior high and high school years when he would spend his summers in Detroit with his cousin and his family.

“Broadly speaking, the thing I remember most about James was how fun-loving he was,” McKnight said. “I remember being 13 or 14, and James coming home from the studio, and as soon as we saw him get out of the car, me and my friends would jump on him … roughhousing for a laugh, you know?

“And he’d just toss us around like little rag dolls because by that time he’d become something of a karate expert, which we didn’t know,” he continued. “Looking back now, I guess you could say he lived his life that same way he approached his music: He was short in stature, but boy, he played big.”

“And he was a prankster with his fellow musicians as well. For instance, there was a time when they were playing in London in the 1960s, and one of the services their hotel offered was a shoe shine.

“The idea was that you’d leave your shoes outside your hotel room door, someone would collect them, get them shined and then they’d be returned to your door and you’d be ready for showtime,” McKnight said. “Well, James delighted in sneaking out and mixing up everybody’s shoes, just for a laugh.”

“If you ever see that documentary ‘Standing in the Shadows of Motown,’ it shows some of the pranks he used to do.”

At the same time, McKnight said, his cousin “was always laid back,” especially when it came to touting his own contributions to the Motown sound.

“I think he would be flabbergasted by the recognition Edisto Island has bestowed on him,” McKnight said. “See, James was never one to brag or anything like that, He just knew his stuff. He always knew his material.

“One of the things I hated about Berry Gordy was he really didn’t give the Funk Brothers their proper recognition, because those guys were the ones that actually arranged most of those songs,” he said.

“Now, I’m not saying Motown’s actual arrangers weren’t good at what they did, but they couldn’t do all of the stuff that the musicians actually did as they got into the song and hashed parts out to see what was going to fit and what wasn’t,” McKnight continued.

“They, meaning the Funk Brothers, were a super sophisticated band. They were jazz guys. They were blues guys. And they were experts in everything they played,” he said.

McKnight went on to recall a conversation he had with Jamerson sometime in the mid-1960s.

“My all time favorite Motown group was always the Temptations, from the first time I heard them, and one evening I remember asking James, ‘Of all the groups you play with, which are your favorites?’” And wouldn’t you know it, he named pretty much everybody but the Temptations.

“I was like, ‘Wait a minute, what about the Temps?’ And he said, ‘Man, that’s all bubblegum sh** I play on that.’ And when he said that, I’m not going to lie, it was like one of my brothers died. [laughs]

“He said, ‘Listen, go back and listen to what I play with the Temptations, and then go back and listen to what I play with the Four Tops. You’ll see a difference.’ So I went back and listened and thought, ‘Oh man, he’s right,’” McKnight said.

Jamerson was among the Motown stalwarts who ventured to Los Angeles, California. in the early 1970s when Gordy moved the label’s headquarters to the west coast, but the spirit that repeatedly propelled its artists to the top of the charts was gone.

After his relationship with Motown ended in 1973, Jamerson found only occasional studio work, though he continued to appear on hits like “Boogie Fever” by the Sylvers and “You Don’t Have to Be a Star (To Be in My Show)” by Marilyn McCoo and Billy Davis, Jr.

Like many studio musicians who played on the hits of the 1960s, including the members of the west coast’s famous Wrecking Crew, Jamerson found himself a victim of his times. Album- oriented rock was now at its peak, and self-contained acts (with only occasional need for side help) were the order of the day.

Even the world of Funk, its roots heavily entwined with Motown, was moving on as bassists began to rely on more repetitive bass lines and a “slapping” technique that relied heavily on a rhythm created with the right hand.

Jamerson just didn’t play that way, and producers half his age began to marginalize him. By 1980, it was all he could do to book a decent gig, and as his career wound down against his will, his consumption of alcohol increased.

He died of complications from cirrhosis of the liver, heart failure and pneumonia on Aug. 2, 1983.

For a time, McKnight left tending Jamerson’s legacy to his cousin’s widow and their children. And for years, interest in the Motown bassist occasionally flickered anew, mostly due to the interest of outsiders — the author of a book, or a magazine writer on assignment — who wanted to learn more about a musician who effectively became a mystery man after his passing.

When the South Carolina Hall of Fame came into being, McKnight decided it was time to leap into action, but trying to get his cousin the recognition he thought he deserved in his home state was only part of his effort.

Not long after deciding to take matters into his own hands, he discovered that Jamerson’s widow had never put a monument or even a tombstone on Jamerson’s grave in Detroit’s historic Woodlawn Cemetery.

“What happened was a friend of mine stopped by his grave and took a picture, and when I got it, all I could see, basically, was a faceplate. So I called up his wife, Annie, and I said, ‘I’m going to give James a headstone,’ but she tried to slow walk it,” McKnight said.

“Whenever something with James comes up, she always says she needs to check with her attorney,” he said. “I’d been through this before, when I wanted to set up a scholarship fund in his name; she said she wanted to do it but had to call her attorney and, long story short, the scholarship fund never got done.”

“Another time — this was back in the day when MySpace was the top social media site — I grew concerned because there were a number of people on there claiming to be James and saying all kinds of hateful things. So I called and asked her if I could start a legitimate MySpace page for James, and again the answer was, ‘Well, I need to talk to my attorney.’

“I said, look, there’s no money involved in this. MySpace is free. There’s nothing complicated about setting up a site, but she insisted she needed to talk to her attorney.

“So this time, I remember, after we spoke, I was standing on my porch with a glass of wine in my hand, and a little devil came and sat on my shoulder and said, ‘The heck with her. You’ve got to do what you’ve got to do?’ And that’s what I did.”

With that, McKnight laughed.

“I always tell people, sometimes when you want to get something done, you not only have to fight the powers that be, you’ve got to fight with your family,” he said.

Not long after, McKnight was on the phone to the cemetery, finding out what could and could not be done on a grave there.

“I was talking to a young woman named Claire Monroe there and she said, you know, your cousin has the most frequent visitors of anybody that’s interred here. And I thought to myself, ‘That’s saying a lot when you think about who’s there: Rosa Parks, the Rev. C.L. Franklin and his daughter, Aretha Franklin, David Ruffin of the Temptations, Levi Stubbs of the Four Tops, a bunch of senators, the Dodge brothers, and so on.’”

Soon, McKnight assembled a dedicated band of supporters, including one he called a critical member of the effort, Prof. Jason Miccolo Johnson of Savannah State University. Over time, his MySpace effort morphed into a GoFundMe campaign.

Next, he called a friend, Nijel Binns, the sculptor who created the Mother of Humanity sculpture in Los Angeles, and asked him if he’d be interested in creating a replica of a Fender Precision Bass, the bass Jamerson used on most of his sessions, to top off the new monument.

In short order, the nameplate on Jamerson’s grave was replaced by a black marble tombstone bearing his photograph and topped with a statue depicting the Fender Precision Bass.

“Basically, the whole thing came together fairly easily, and now that it’s done, when people walk through the graves to try to find James Jamerson, they’ll see that doggone base coming out of the top of the headstone and know they’re in the right place. You literally can’t miss it,” McKnight said.

Most people responded favorably to the Jamerson monument, but McKnight said his cousin’s widow was still reluctant to embrace it.

“She said, ‘Okay, you’ve done the headstone, but everything else you plan to do has got to go through me, and the family’s attorney, and you’ve got to get permission first,’” he said.

“I looked at her like the RCA dog,” McKnight said, referring to Nipper, the dog in Bristol, England, who served as the model for the painting ‘His Master’s Voice’ by painter Francis Barraud.

The image of the dog tilting its head to one side listening to a windup gramophone, or record player, later became one of the world’s most famous trademarks, appearing for years at the center of every RCA Record.

“I said, ‘Look, I’m just doing this to keep my cousin’s name alive, and to keep him at the forefront … you’ve got to realize who your husband is — history tells us he was the most influential bassists of all time. And if you don’t want to promote that, somebody has got to pick up the mantle and do it,’” he said.

With that, McKnight turned his attention back to South Carolina, and resumed his fight against what he dubbed “the good old boys network” that runs the S.C. Hall of Fame.

“I mean, it just seems stupid not to recognize him in his own state,” McKnight said. “When he went into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2002, I thought he’d be a shoo-in for the state hall of fame, but then nothing happened.

“I mean, this is a man who received two lifetime achievement Grammys, who has been inducted into the Musicians Hall of Fame, and who, along with the rest of the Funk Brothers, has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame,” he said.

“What the hell is wrong with South Carolina? That’s always been my favorite question,” he said.

The Well News reached out to the South Carolina Hall of Fame for comment, but thus far has received none.

A review of its website, however, suggests it’s been slow to honor musicians.

James Brown, the “Godfather of Soul,” who was born in Barnwell, South Carolina, and lived in poverty in Elko, South Carolina, until his family moved to Augusta, Georgia, while he was a child, isn’t in the state hall of fame; neither is the great Brook Benton, the popular singer-songwriter and native of Lugoff, South Carolina, best remembered today for his ballad “Rainy Night in Georgia,” a hit that is still heavy featured on SiriusXM radio and covered countless times, most recently by Boz Scaggs.

And lest one be tempted to suggest race is involved, the South Carolina Hall of Fame has also ignored Hank Garland, a native of Cowpens, South Carolina, who gained renown as a session player for Elvis Presley.

Garland joined Presley’s studio band after a dispute over pay led to the departure of Scotty Moore and Bill Black, who had, up to that time, been the core of Elvis’s band,

Garland’s first session with Presley was intended to keep the singer in the public eye while he was serving in the Army and produced a string of hits that included “(Now and Then There’s) A Fool Such As I,” “I Need Your Love Tonight” and “A Big Hunk O’ Love.”

Garland was still in the Elvis-fold when Presley returned from the Army in 1960, lending his unique guitar sound to “(Marie’s the Name of ) His Latest Flame,” “Little Sister” and “Can’t Help Falling in Love,” among others until a tragic car accident cut short his guitar playing career.

Another musician from South Carolina with Elvis ties, who is also not in the state hall of fame, is Bill Trader, of Darlington, South Carolina, who actually wrote “A Fool Such as I” and had his songs recorded by dozens of other artists, including Hank Snow and Jo Stafford.

“Nothing against Darius Rucker,” McKnight said. “But Jamerson was making good music before Darius was even born.”

Frustrated after 20 years of trying to get the South Carolina Hall of Fame to recognize his cousin, about three years ago, McKnight decided to try another tactic — If the state as a whole wouldn’t honor Jamerson, maybe his hometown would.

The only problem was determining how to honor Jamerson’s memory. McKnight said like many rural communities, Edisto had changed considerably since the bassist’s childhood in the 1930s and 1940s.

“There’s really nothing left that I know of in terms of places he might have been or spent time in,” McKnight said. “The closest thing we have to a James Jamerson site is the green house that sits behind the Jane Edwards Elementary School.

“The school is new, but the house — which was the elementary school in Jamerson’s day, and which he went to — still stands, but other than that, it’s pretty sparse in terms of landmarks,” he said.

Eventually McKnight and Jamerson’s supporters hit upon the idea of recognizing the bassist on a road he was known to travel, as they hadn’t changed as much, and the location on Steamboat Landing Road quickly rose to the top of the list.

“It was the road that led to my grandmother’s house,” he said. “And it was the road he would have taken to get to the piano that formed his musical roots.”

McKnight petitioned the state House and Senate to change the name of the road, and lobbied for it until this past session, when the bill finally cleared both chambers.

Though McKnight had hoped the road would be named James Jamerson Way, the legislature went for the more formal James Lee Jamerson Memorial Highway.

“I didn’t mind,” McKnight said. “The main thing was it was a reality. It took me three years, but I got it done.”

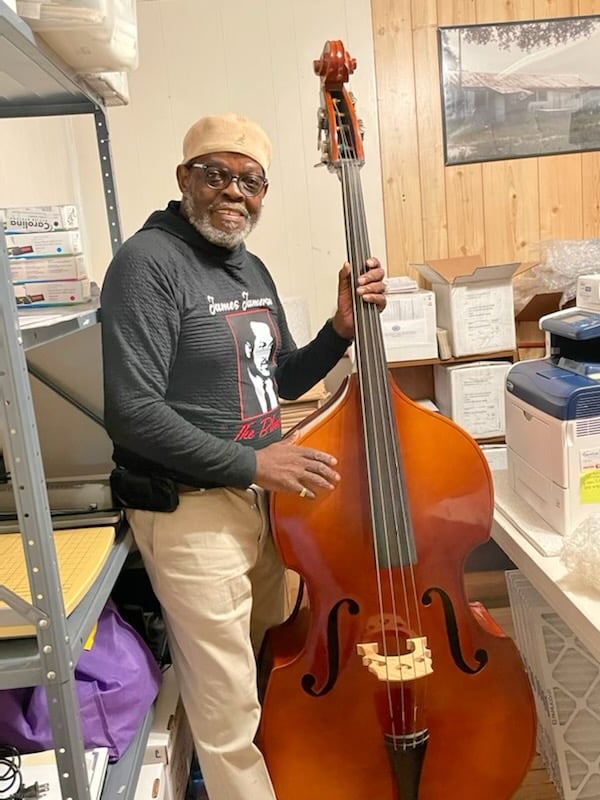

And while he waited, he found yet another way to honor his cousin, hosting the annual James Jamerson Bass Symposium each October in historic downtown Charleston.

This year’s evening of music and celebration is being held at Festival Hall on Beaufain Street, a somewhat larger venue than in year’s past. It will feature performances by the Charleston Funk Brothers and the Black Velvets.

“The main thing I’m trying to do with these events is open people’s eyes to what someone … like them was able to accomplish in his life, especially the young people,” McKnight said. “I mean, as we’ve been discussing, my primary goal in starting all this was to keep my cousin’s name alive, but I do think learning about James and hearing his music can be an inspiration for the young people in our community.

“In fact, while we were in Edisto for the street-renaming and concert there, I stopped by the elementary school and left a Jamerson display, consisting of a framed poster and a little plaque, in the cafeteria, just so the kids can continue to make a connection with him,” McKnight said.

Jamerson’s next moment in the sun will come next spring, when he’s inducted into the South Carolina Entertainment & Music Hall of Fame in Greenville.

“I just found out Monday,” McKnight said. “It’s a very, very nice development.”

But will it salve the wound caused by the indifference of the state hall of fame?

“You know, somebody just asked me that the other day,” McKnight said. “They said, ‘If the South Carolina Hall of Fame came knocking, would you tell them to take a hike?’ And I said, ‘No, of course not. I fought for Jamerson to get in for 23 years. So my response would be thank you. Thank you very much.’”

Another question McKnight often fields is whether he’s ever been surprised by how much time he devotes to the cousin’s legacy.

“Let me tell you a story about that,” he said. “Many years ago, after trying and failing to get James in the state hall, I sat here in my home, where I’m surrounded by a bunch of his pictures.

“Now, this obviously wasn’t an unusual occurrence, but this one day as I sat down and I looked up at the pictures and said out loud, ‘Why are you haunting me?’ And just like he was in the room, and as clear as I’m talking to you now, I heard him say, ‘You’ve got to tell my story.’”

McKnight laughed.

“It’s true. I heard him plain as day. And after initially responding, ‘Get out,’” he continues with more laughter, “I’ve pretty much been working at it every day since.”

Dan can be reached at [email protected] and at https://twitter.com/DanMcCue