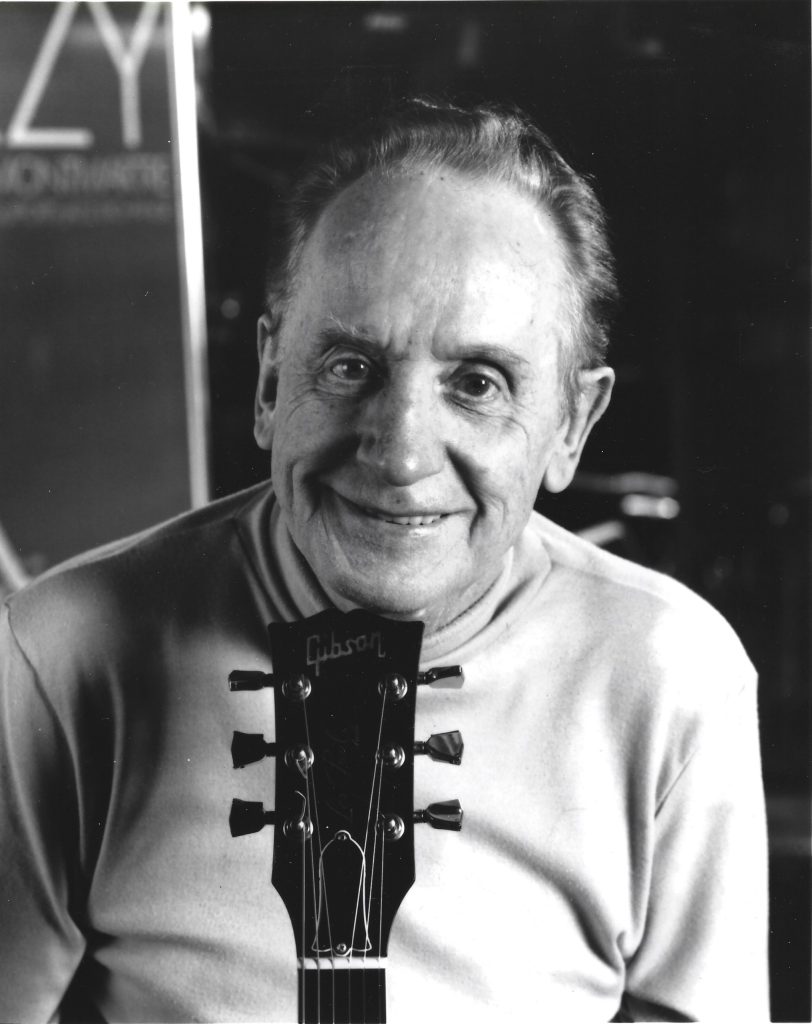

American Genius: Recalling the Inventor/Guitarist Les Paul

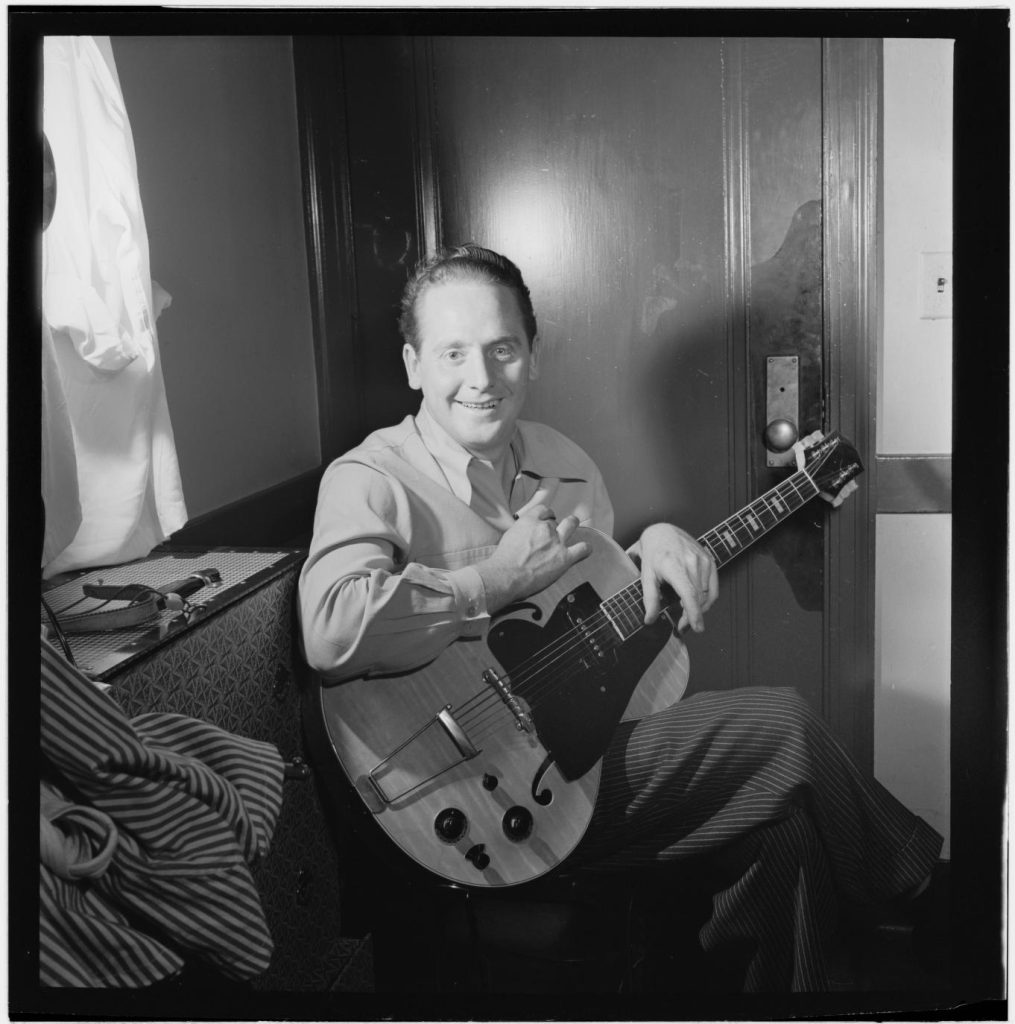

NEW YORK — The very first face-to-face conversation I ever had with Les Paul, the legendary jazz guitarist and inventor, took place oddly enough in the men’s room of Fat Tuesday’s, a then-popular nightclub located at 190 Third Avenue at 17th Street in New York City.

It was the early spring of 1988 and while it would be a stretch to say I was an “aspiring journalist” at the time, I was certainly leaning that way.

Increasingly that year, I found myself spending my spare time in college writing about musicians and comics for a succession of small, mostly forgettable “freebie” publications, the kind that college kids turned to to see who had the best drink specials for the upcoming weekend.

Up to this point, most of my “gets” were interviews I scored for myself, mostly with older artists, and mostly, in this pre-internet, pre-email age, with the help of local musicians’ unions.

It was, as one might imagine, a drawn-out process. I’d go to the library to look up a union local’s address, then type out a letter — my freehand writing being almost illegible — hoping they could direct me to someone I hoped to talk to, usually a musician whose glory days were long past, but who continued to hold some fascination for me.

In time my list of successes included interviews with Johnny Johnson, the piano player Chuck Berry immortalized as “Johnny B. Goode”, J.I. Allison, the drummer for Buddy Holly who’d married the real life “Peggy Sue,” and the surviving members of Elvis Presley’s original backing band.

Catching up with Les Paul was a little more straightforward. In his case, a tiny ad in The New York Times alerted me to the fact he’d started a Monday-night residency at Fat Tuesday’s and I dropped him a letter.

A short time later the letter was returned, with a note written in the margin. “Call me,” Les said, and he provided his home phone number.

When I finally worked up the nerve to dial it, the legend turned out to be a marathon talker, and over the course of an hour or more he effectively told me his entire life story.

“Phew,” I thought as it sounded like he was wrapping up. “I’m so glad I had a 90-minute tape to record all this.”

Then Les invited me down to the club so we could talk further. Little did I suspect it was the beginning of a series of conversations that would transpire over the next four years.

It was the April of the fractious Democratic presidential primary in New York. The Democratic contest among Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis, Rev. Jesse Jackson and Sen. Al Gore of Tennessee had been polarizing.

Four years earlier, Jackson had referred to Jewish people as “Hymies” and to New York City as “Hymietown” during a conversation with a Black Washington Post reporter, Milton Coleman.

Jackson had assumed the references would not be printed, but several weeks later Coleman permitted the slurs to be included far down in an article by another Post reporter on Jackson’s rocky relations with American Jews.

The Nation of Islam’s radical leader Louis Farrakhan threw gasoline on the fire by coming to Jackson’s defense, warning the Jewish community, in Jackson’s presence, that “if you harm this brother, it will be the last one you harm.”

Jackson finally largely put the matter to rest with an emotional speech before national Jewish leaders in a Manchester, New Hampshire, synagogue.

But Jackson refused to denounce Farrakhan, a decision that would haunt him during a primary season in which he was generally outperforming the predictions of the experts.

In 1988, driven in part by the city’s tabloids, the N.Y. Daily News and N.Y. Post, New Yorkers had not forgotten, though New York Mayor Edward I. Koch also played a decisive role, suggesting that Jews would have to be “crazy” to vote for Jackson.

In the end, Dukakis scored a decisive victory, with Jackson coming in a strong second. Exit poll data showed that a majority of New Yorkers went to the polls either to vote for him or against him.

“Boy, did you ever hear such a racket?” Paul said of the election when I saw him at the club a week ahead of the primary.

To get into Fat Tuesday’s one had to walk a flight of stairs down to a vestibule, where a woman at the standing maître d’s desk collected the modest price of admission. To the left was a small coat room and the restrooms.

To the right was the club proper, a dark, rectangular space, with the stage against one of the longer walls, and the tables set perpendicular to it. It was a tight space, and after I ordered a beer, which looked to be at least a quart, I feared I’d effectively be trapped during the show with a swelling bladder. With that, I excused myself and headed off to the men’s room.

Pushing open the door, I was stopped dead in my tracks. I may have even stepped back a little, for there was Les Paul himself, combing his hair in a mirror above a small sink.

“Howdy,” he said as he turned to face the door. Wide-eyed and smiling, he added, “Les Paul.”

I introduced myself, and with that, Les was off on another monologue.

Paul didn’t dwell on current electoral affairs, however; after a few brief remarks about how loud and nasty the primary had been, he was off on another tangent.

“You know, it kind of reminds me of when I played the White House for FDR in 1939,” he said.

Another long anecdote ensued. And that’s kind of how our relationship was. I would never presume to say we were friends, but we were definitely regular acquaintances, and as his residency continued, there were plenty of reasons to catch up and resume our conversation.

There was, for instance, the release of a career-spanning box set. Six months or so later, there was the celebration of the 100th broadcast of On Stage with Les Paul, which was taped live each week at the club and later rebroadcast.

Ultimately, in search of a fresh angle, I traveled to the guitarist and inventor’s home in Mahwah, New Jersey, to see his technical handiwork in its natural setting. I got more than I bargained for, however, when it turned out several of his most noteworthy inventions had been moved from his “lab,” which was actually his garage, to his living room for shipment to the Smithsonian.

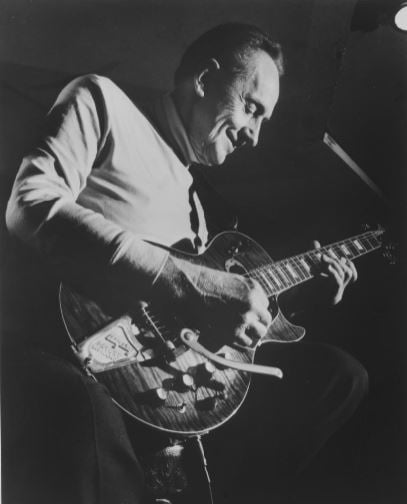

Anyone who ever heard Les Paul play couldn’t help but recall the shimmering, Space Age, far-out sounds he coaxed from the solid-body electric guitar he invented.

And his “other” inventions, including sound-on-sound and multitrack recording, would revolutionize the recording industry. Until the day he died in August 2009, he was an American original and certainly, an American genius.

For those who don’t know who he was, here’s a brief biographical sketch.

He was born Lester William Polsfuss on June 9, 1915, in Waukesha, Wisconsin, and began inventing things, including the harmonica rack for guitar players, before he reached his teens.

Though others, including Leo Fender, lay claim to having birthed the solid-body electric guitar, Les Paul was certainly among the earliest to independently experiment with its design and construction.

His own prototype, nicknamed “The Log,” eventually inspired the design, sale and marketing of the Gibson Les Paul, an instrument that has, since its introduction in the late 1940s, sold in the millions.

Paul taught himself how to play guitar, and while he is mainly known for jazz and popular music, he had an early career in country music. In the 1950s, he and his wife, singer and guitarist Mary Ford, recorded numerous records, selling millions of copies and became household names by hosting their own television show.

Among Paul’s many recording innovations are sound-on-sound — known more commonly as “overdubbing” — numerous delay effects, including electronic echo and phasing, and, of course, the invention of multitrack recording, the technique that made Les Paul and Mary Ford’s recordings so unique and unforgettable in their day.

Though honored many times during his long life, Paul is one of a handful of artists with a permanent exhibit in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. He is also the only inductee in both the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

The interview that follows is a composite of our multiple conversations. As he did with sound, Paul tended to add more detail and nuance and made several passes at an interview. Where necessary, additional notes have been added to lend context to the subject at hand.

It starts after Paul asked how I’d gotten into the writing game.

DM: This all started as a fluke, really. I started writing about comedians, but music was what I really wanted to write about. …

LP: Well, you hit the mark with me, because I do both.

DM: You know, I’ve heard that you’re kind of risqué in the clubs …

LP: [Laughing] Well, it all depends upon what the subject is, right? Sometimes, they get to the nitty gritty. … Someone throws something out and why, you go with it. … But, generally, I’d say the show is not too risqué.

To me, it’s a great thing to have the people there … and to bring them in so that they feel like they’re in our kitchen and this is part of a rehearsal in my living room, you know?

So by the time they’re down there and I’m on the stage for two minutes, they feel like they’re part of it.

[At the time, Paul was playing a regular, Monday night residency at Fat Tuesday’s, a basement jazz club located on 3rd Ave. at E. 17th Street. It closed in the mid-90s.]

In other words, no one thinks anything of getting in on the act, which is very nice because I love to have a rapport with the audience.

DM: Has that been true throughout your career?

LP: Yes. Yeah. And I’ve been criticized for it by people who say you should be above your audience. …

I mean, I remember playing for the king and queen of England … I was criticized terribly by the publicity department, management and so forth when we got off the plane in London. I mean, people actually said to me, “You’re too earthy. You should rise above it and not stop to sign autographs and that kind of thing.”

And my response was, “But that’s the way we do it.” All my life. I’ve never been out to impress anybody. I’m always out there with the people. And that’s a part of the great privilege, to be able to talk to people who like you.

A Japanese man came up to me once … and he only knew a very little bit of English, so he’s … trying to communicate, and the other fellow who was with him, also Japanese, was trying desperately to bite his lip and not embarrass the other guy.

So finally, they make their way to the bar and I got up on stage and the first song I played was “Japanese Sandman,” or something like that … and suddenly I hear the man shout, “I love you.” [Laughs] I mean, the connection you can have with people if you’re just open to it. It’s amazing.

And in this case it’s because I acknowledged him with my playing … while he and his friend were at the bar … and he had tears in his eyes.

DM: How many songs do you think you know?

LP: You wouldn’t think I knew any if you heard me. [Laughs loudly]. God knows, I have no idea. I have no idea how many records I’ve made or how many were sold or anything else. I never paid much attention to that.

DM: Do you remember your early learning experiences, when you first picked up a guitar and said, “This is for me?”

LP: Of course.

DM: Did you learn from books? Have a teacher?

LP: I got a book called the E-Z Method. It had a big “E” and a big “Z” on it, and I think it was something like 10 cents. It came with this little Troubadour guitar from Sears and it showed you where to put your fingers and everything and I learned a little bit from the charts in that. It was just a 10-page book, but I learned “Mary Had A Little Lamb” from that.

The main way I learned about playing the guitar, though, was by going to the local theater when Gene Autry would appear in person with the WLS Barn Dance show and I would sit in the front row with a friend of mine.

I’d sit there with a pencil and a piece of paper and when he’d finger a chord, my friend would put on this little flashlight and I would put a dot where his fingers were on the fretboard.

DM: You’re kidding.

LP: No, it’s absolutely true. And this one time, after we’d been doing this for about two days of performances, Autry stopped mid-song and said to the audience, “I’m sorry, but I’ve just got to stop the show for a moment. There’s something that’s been bothering me. It seems like every time I play an F chord, a light goes on in the audience.”

Now, the thing is, at this point, I’m so caught up in what I’m doing that I’m not even listening to what he’s saying. I’m just making my notes. Trying to make sure they’re accurate. And Autry says, “Can somebody explain to me why, when I play this chord …” And of course, my friend, who is as caught up in what I’m doing as I am, lights the flashlight.

So now, it’s me and my friend who are the center of attention. And I say, “Mr. Autry, I am truly sorry, but I’ve been trying to figure out what you’re doing up there.” And he says, “Can you come up here?” and he brought me up on the stage and I sang a song [begins to laugh] and it started a big thing in my hometown of Waukesha, Wisconsin, let me tell you.

DM: Now, that sounds like you were almost trying to do live transcriptions of chord shapes. You can read music, can’t you?

LP: Oh, of course.

DM: How would you rate yourself as a sight reader?

LP: Not very good. … I’m pretty bad at sight reading, actually. But I sure know my instrument.

DM: Were there other techniques that you developed to learn songs early on?

LP: Well, you know, it’s a very wrong statement to say that I was self-taught. Nobody is self- taught. You learn from somebody else. I listen to everybody. I watch everybody. To this day.

If there’s something on MTV and there’s a kid on there playing the guitar, I stop and watch. I want to see anything coming down the road. I want to know what he’s doing and how he’s doing it.

So you have to stay with it at all times. I’m constantly learning. Here I am going on 73 and the thing I do most is improve. You know guys say, “For his age, he’s playing pretty good.”

I’m playing better … and the way you play better is to keep learning. You get out there and you’ve got to keep up with what’s happening. You don’t have to necessarily agree with it. I don’t particularly dig a million decibels of sound from an empty head. But awareness of what’s happening is important.

Personally, and I once said something to this effect, I believe that if you can’t hum it, if it’s not romantic, if it doesn’t have a melody, then it’s not music. It was something like that, and Paul Harvey picked up on that and repeated it on his radio program and a bunch of articles came out in newspapers and magazines, based on that statement.

DM: A lot of people would shy away from confrontational statements like that.

LP: That’s true. … particularly when you’re in my position, trying to sell my guitars to players who are primarily rock and roll players. But I’ve always felt that if something sounded lousy, I should say it. And if something sounds good, it’s good. It’s like anything else.

DM: I know early on in your career you played country music as Rhubarb Red and jazz as Les Paul, but that caused me to wonder about your exposure or lack thereof to the blues or rhythm and blues while you were coming up?

LP: As a matter of fact I got a letter from a guy just today who asked whether I remembered him. He said, “Do you remember the bass player you worked with in 1931? We made a bunch of R&B records with Georgia White: “I Got The Toothache Blues,” “Little Red Wagon,” “Whatcha’ Got Your Trombone For” … he named them all.

I used to make what they then called “race” records in Chicago. That was one of my things … to play dirty down rhythm and blues and blues harmonica, and then as Rhubarb Red, I was actually a bluegrass picker. I was not a cowboy singer, I was picking bluegrass and singing bluegrass.

DM: Now, aside from being acknowledged as a stellar musician, you’ve been credited with inventing the solid body electric guitar. It’s one of the first things people tend to say about you. But acoustic guitars were already around, obviously. What was wrong with them?

LP: [Starts to answer. Pauses to consider his response.] It’s very simple. You have to have a pickup underneath the strings. The strings actually break the flux … the magnetic field … you with me?

DM: So far.

LP: Okay. So if you hold something stationary and the string vibrates, you now have the sound of the string.

Now, if you put it in a hollow-body guitar and you pluck the string, the top of the guitar is where the majority of the sound is created. … So the top is vibrating one way and the string is vibrating another way and consequently, you have a disagreement between the vibrating sources.

You have two sources instead of one source. And as soon as you have two sources, one of them is liable to be 20 degrees out of phase. Or 45 degrees, or 50 or 60 … and ultimately, because of that, it is liable to stop vibrating — it may continue to oscillate to a degree — it might continue to vibrate at a certain note that happens to be the very same pitch as your instrument, but it’s not the natural sound of the string.

DM: Okay, I think I’m following you.

LP: Okay, well, say you’re playing an acoustic guitar and there’s a bass player playing next to you, or a piano player or a drummer. If you take that guitar and just hold it up, not playing it, when the bass player starts playing, you can feel with your hand that your guitar is starting to vibrate. This is a normal thing. This is how Caruso could break glass, by singing the resonant frequency of the glass. That’s what you call the free resonance.

DM: Right.

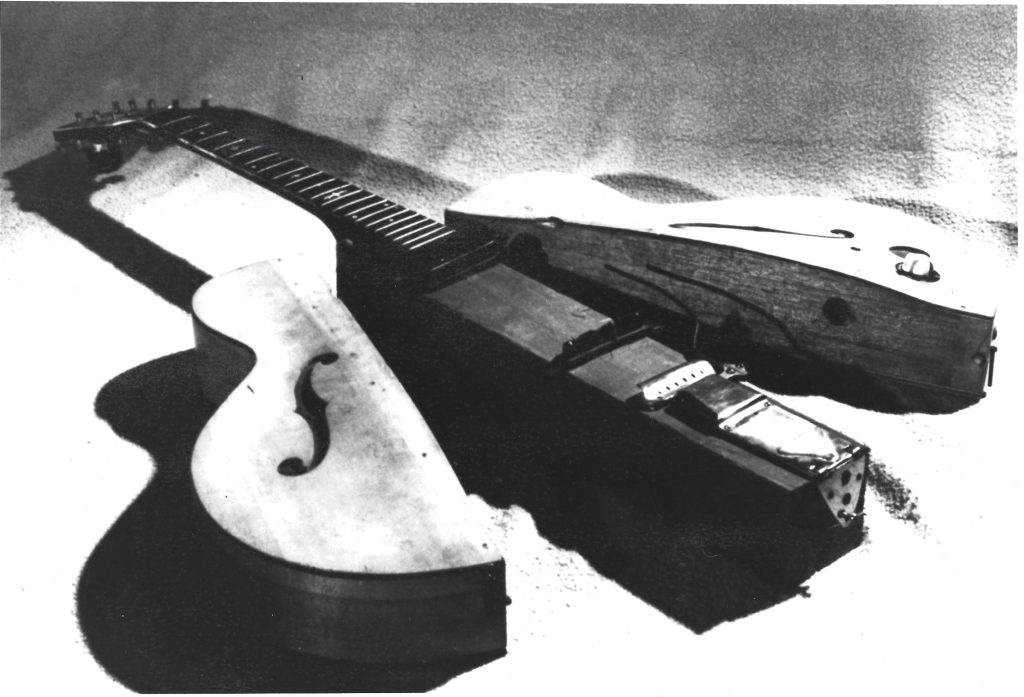

LP: Well, I learned as a little kid, way back in the 1920s, that only one thing should move and everything else should stand still. So I just put the acoustic guitar aside and said, “I’m going to take a string and stretch it across a piece of railroad track.” That’s solid steel. And immediately, I put a pickup under it — which, incidentally, was the earpiece of a telephone — and when I put it underneath there, I immediately heard what I wanted to hear: The guitar string uninterrupted, or unenhanced, or altered in any way by the top of the acoustic guitar doing its thing and the string doing its thing.

Once I’d proven that point to myself, I went a step further … taking a piece of balsa wood and stretching a string across that. And that created the worst sound I ever heard. So now I was sure that the rigidity of steel was far better than a much softer, more flexible material.

DM: Rock beats paper?

LP: Something like that. I now knew what I wanted was solid mass. And so I went with the solid body theory and of course, for a period of time, I was kind of a laughingstock. It took me, maybe, 10 years to convince the Gibson people that it was a practical idea.

They all looked at me, the people at Gibson, Epiphone and so on, as the character with the broomstick with the pickup on it.

DM: How did you keep from getting discouraged?

LP: Well, I can’t say I didn’t get discouraged. I knew I was on the right track, but I kind of let the project fade to the background for a time. I put it in the corner, didn’t do anything about it. And it just sat there until about 1937, when I started tinkering with it again.

In any event, by 1941, I knew where I was going with the electric guitar, and to prove that point one more time, I made “The Log,” which was a 4×4 piece of wood with wings and a pickup on it, attached to a standard Epiphone neck.

I built it over the course of three Sundays at the Epiphone factory in New York City, and still Gibson took little interest in it.

Years later, this is maybe 10 or 12 years ago, I was up at the Mayo Clinic, just for a checkup, and who do I run into but M. H. Berlin, the former president of Gibson guitars, who was probably up there for the same reason.

So we arranged to go to lunch. He had his girlfriend with him and I had mine and we were sitting there, eating and he said, “You know, we laughed at you for years. Did you ever dream that we’d one day be making one of your guitars every three minutes? And that it would be the most valuable instrument in the whole world? Did you ever think the guitar was going to get this big?”

And I said, “Of course. There wasn’t a doubt in my mind.”

It’s almost like when someone asked me, “Did you ever think you were going to get with Bing Crosby?” I said, “Sure … and I knew exactly when.” My life has been planned. I plan everything I’m going to do.

For instance, people ask all the time why I save all the things that I’ve saved over the years. And I say, “So that it can go to the Smithsonian Institution.” And occasionally someone will say, “Well, how did you know that it was going to go there?” And again, I’d say, “Because I planned for it to go there.” And you do. I do, anyway.

I saved my first harmonica rack. I saved my first guitar. I saved these things because I knew someday these things would be part of the history of what we were building.

But, yeah, I plan everything. I practiced for two years with my trio and then said, “Now we’re ready to go to New York.”

And I told the other members of my trio, Ernie Newton and Jimmie Atkins, that we were going to play with the bandleader Paul Whitman. Well we couldn’t get to Paul Whitman, but we got to Fred Waring, and he was just as good. [Laughs]

Sometimes there’s a detour, or a bridge has washed out, which means I may have to make a few changes, but I get right back on the highway.

DM: Did you plan to call your invention the “Les Paul” guitar?

LP: No, I didn’t. I hadn’t really thought about it. But when it came time for it to go into production, the folks at Gibson said we needed a name. I think they were afraid it would bomb. Someone said, “You know, we might not want to use the name Gibson on it, do you have any suggestions for a name?”

And I just said, off the top of my head, “Why don’t you call it a ‘Les Paul’ guitar?” And they said, “Would you put that in writing?” And I said, “Sure, I’ll put it in writing.” And that was their first mistake. [laughs]

You know, recently a guy walked into Fat Tuesday’s with one of the early prototypes — one of the real early, early models of the Les Paul — and I was floored. I said, “Do you realize what you’ve got here?”

He was a young guy and he said, “No, what have I got?”

And I started saying, “Well, I don’t know where you got it, but …”

He says, “Well, my dad recently died, and it was laying under the bed.”

I said, “Well, that guitar you’ve got there is worth $20,000 or $30,000. Go ask anybody around here. Heck, I bet you can sell it right now at the bar for at least $10,000 to $15,000.”

DM: Now, let me step back a little here, because your inventing gadgets of all sorts really predates your involvement with the guitar.

LP: You could say that … I built my first crystal radio set when I was about 8 years old, and began studying audio and electronics with a local radio engineer shortly after that …

DM: And then the guitar comes along … and if I’m not wrong, shortly after that, you start performing, which leads to your first experiments with amplification.

LP: That sounds about right.

DM: So where does a kid — I’m guessing you were about 13 at the time — get a piece of railroad track?

LP: Well, what happened was I kept tinkering with amplification and eventually I ran into the problem of the guitar howling. This was another factor leading me to conclude an electric guitar should have a solid body, rather than the hollow body like an acoustic guitar.

And so a couple of friends of mine and myself went over to the railroad yard and … stole a wagon. We didn’t take the horse, but we took the wagon and a piece of railroad track. … It was about a yard long and it was … heavy for us kids to lift.

But that was the railroad tie that I stretched a string across, alongside a set-up in which I stretched a string across a soft piece of wood. I wanted to compare the extremes and see which one was better. And the railroad track won.

Of course, I immediately came to the conclusion that my idol, Gene Autry, would never sing from the back of a horse while playing a piece of railroad track. … So further experiments were needed.

Eventually I made one solid-body guitar with a one-inch top and painted f-holes on it. And that was in about 1929, I think.

DM: So you’re still only about 14 at this point.

LP: Right. And it was right about this time that I started performing around Waukesha as “Red Hot Red,” and eventually I wound up playing at a place called Beekman’s Bar-B-Q Stand. It was about halfway between Waukesha and Milwaukee.

I started out with my harmonica and a guitar, and I’d taken the mouthpiece of a telephone and I was using that as a microphone, to sing into … amplifying the sounds through my mother’s radio.

Well, the tips were pretty good and the carhops kept coming back to tell me I was getting good feedback from the people sitting in their cars, eating their barbeque sandwiches and washing them down with beer.

The problem was, you could hear my voice, but you couldn’t hear my guitar. So I decided to do something about that and the first idea was to take a phonograph needle and jab it into the top of the guitar, to catch the vibrations. That wasn’t very successful.

The next thing I tried was putting the telephone mouthpiece over the strings and that worked much better. That’s how I found I had the sound of the electric guitar.

Now this goes back to your question about what was wrong with the acoustic guitar. Well, I had this idea or concept of a sound in my head and I heard it “for real,” you might say, when I was doing this experiment.

I came to the conclusion — and it was clearly understood between me and myself — that this was what I was trying to accomplish. It wasn’t to make an electric guitar sound like a standard acoustic guitar, only louder. It was to be able to play with a truly electrified sound.

It’s kind of like buying a suit in a way. You can buy a suit and then take it to a tailor and have it altered any way you want to match your identity and what makes you comfortable. This is what I did with my guitar. I custom made it so it gave me exactly what I wanted.

I don’t invent anything unless I’ve got a problem and there’s nothing out there I can buy to solve it. I know there are people out there who probably have lists of things they’d like to invent, but I was never that way.

[In a later conversation, we revisited the subject of inventing.]

LP: Wherever I was, it [inventing] followed me. If I was on tour, you’d find me in the dressing room fooling with it, and if I was home, I’d be in my lab doing it. It was part of me. You’re constantly thinking about it, or periodically thinking about it. It’s like, something turns you on and you’ve got a little time to do nothing, and rather than go off and play golf, you say, “Well, I’ll do that.”

DM: Did you ever have something that just did not work, that went haywire on you?

LP: Sure, all kinds of inventions. I’ll find one that absolutely works on paper and absolutely doesn’t work at all otherwise. And I’ll find others that work, but you can’t make 10 in a row that work.

Another situation is when you have something that works perfectly when you hold it in your hand, but fails as soon as you mount it.

Now, one thing I’ve learned through this process is that many successful inventions are arrived at by accident. So it’s incredibly important, if you set out down this road, that you keep track of what you’re doing each step of the way.

It’s great to come up with something good, but you better know how you got there because you run into a lot more failure than success, I’ll tell you that.

That’s one of the reasons I told Gibson I want to see nine out of 10 right before we go into production. Of course, nobody listened to me at first and the first couple of hundred that came off the assembly line were flawed in some way.

DM: I know you faced some resistance as you tried to get your innovations out into the world. Do you feel a special sense of gratification related to the popularity of the Gibson Les Paul or to the role you played in inventing multitrack recording?

LP: Well, I feel great. And you’re right, it was always a process of overcoming resistance. I mean, at the time I invented echo, sound-on-sound, eight-track or multitrack, all those techniques that are now considered standard techniques, all those things were looked down upon as trickery or some gimmick or something like that by the first people that heard them.

The way I looked at it at the time was, “Geez, I’d like to do that or do this, but there’s nothing out there to do it with.” So I’d invent it. The only reason I made it was because it wasn’t out there.

Edison made the light bulb, I guess, because he got tired of the candle flickering and he felt as though he needed a light bulb, so he made one.

My reason, and maybe I shouldn’t even make an analogy, was just in plain fact, I needed them. I just finished designing new strings that are … just leaps and bounds ahead of the strings that are out there now, and it was just a question of my getting sick and tired of playing with bad strings. So I put everything aside and took a couple of months to make a string that was right.

The electric bass, I brought that about — it wasn’t in existence until I brought it about — because my bass player quit. I didn’t have a bass player and Mary said, “What are we going to do?” And I said, “I don’t know yet, but I’ll know when it’s time.”

DM: I wasn’t aware of your connection to the electric bass.

LP: Oh sure. This whole world today just seems to surround what happened in my life. It just seemed like the right thing to do, so I did it. I’m surely not bragging about it. I very rarely think about it. I’m not impressed with it. I’m shocked mostly, with all that has grown out of it.

You know, very few people know this, but Mary and I only made one song on the multitrack machine I came up with; almost everything else was made on acetate disc — using two-disc machines, which I made using Cadillac flywheels. They were the turntable.

They were recently sent off to the Smithsonian, but I had a photographer over, taking pictures, and if you ever get to see them, you’ll crack up. But it worked out great because nothing is more dynamically balanced than a Cadillac flywheel.

DM: Really?

LP: [Looking sheepish] Well, it could have been any flywheel. It could have been a Ford flywheel, but I used one from a Cadillac because it sounded better — not audio-wise, but when you were speaking to someone about it. [laughs]

DM: Let’s talk a little more about your early years in music. You mentioned earlier you knew you would someday play with Bing Crosby. How did it happen?

LP: Well, like everything else, you plan and you have your dreams. It all grows from the childhood fantasy where you could say, “Boy, someday I’m going to be as good as Gene Autry.” Then you set your next goal.

DM: Bing Crosby.

LP: Right. So I get this trio together and I tell the members, this is what I think we’ve got to do to make the big time, this is what we have to have: you’ve got to have a vocal because a vocal is terribly important. And I said, we’re going to do pop music, which is what Crosby was doing at this point.

What happened was, I took two years to get this trio together and after two years of practicing, two or three times a week, I had a guitar player who sang, a bass player who did comedy, and me, fronting the trio. And finally I said, “Well, we’re ready to go.”

So we packed up the car, tied the bass to the roof and flipped a coin. Heads, we go to New York. Tails, we go to Los Angeles. And it came up heads. The two other guys say, “What the heck are we going to do in New York?” And I said, “Oh, I know Paul Whitman; don’t worry about it.”

DM: I have a sense by the way you’re talking that …

LP: I know where you’re heading, and you’re right. I didn’t know Paul Whitman at all, but I told them I knew him. Just to get us on the road.

We get to New York and go to Whitman’s office and I can see him in the back office as we approach the reception desk. I also see him motion to his secretary to shut the door, in our faces, you know?

And so we’re standing in the hallway and my bandmates say, “We thought you knew this guy.” So I try to talk my way out of an embarrassing situation by saying, “Well, you know, the light wasn’t very good.” I’m just making all kinds of excuses … when all of a sudden, Fred Waring comes by and sees us and says, “If you guys are looking for a job, I’ve got 62 Pennsylvanians that I can’t afford to feed — the Pennsylvanians was the name of his orchestra — so I’m sorry, but …”

I say, “Mr. Waring, the elevator is all the way down on the 1st floor. Can we at least play for you until it gets here?” He says, “I don’t think I can stop you.”

So we played two songs — just two songs, but we knew them and we knew them good. And he took us down to where his band was rehearsing and we did our two numbers again, and right then and there, we were asked to join his band.

We stayed with him for five years after that, and all that time, I had my sights set on Bing Crosby. I idolized the guy and said, “That’s where I’m going next.”

After five years I turned in my notice and Waring said, “Where are you going?” I said, “With Crosby.”

Waring looked surprised and said, “Crosby’s hired you?” And I said, “No, he’s never heard of me, but he will.”

DM: What did the other members of the trio say when you announced you were leaving?

LP: Oh, they were coming with me.

DM: So you resigned for everybody, without knowing Crosby?

LP: Right. Now, Crosby at this point, of course, is doing movies in Los Angeles. So we traveled out there and I set about finding the door he used to come in and out of the studio and what his daily routine was, and when I figured that out, I told my guys, “We’re going in that door.”

What happened next was, one afternoon, as the musicians filed out of the studio for their lunch break, we tried to sneak in. We sort of walked backwards and turned to go in, like we had forgotten something, and we got caught by the guard.

I said, “We forgot our music.” And since I had my guitar with me, he believed me. Once inside, we picked out a studio that didn’t have anything happening in it, set up, and began playing.

“What for?” the guys asked. I said, “Somebody’ll come along.” And sure enough, eventually somebody did. He poked his head in, turned, left, came back and it turned out the guy was the musical director at NBC. And he hired us to be members of the studio band.

DM: Okay, so how does this connect you with Crosby?

LP: Well, now we’re in the building every day and I’m continuing to find out what Bing did when he was there. What I noticed was that he’d walk down to this little room down the hall marked “E,” this was in 1941, and the “E” stood for “essential.” It was filled with air-raid stuff and emergency supplies. And sure enough, he goes in there and rehearses every Thursday at 4:30.

What I did was I got permission to rehearse there the next Thursday at 4:15. The afternoon I set the guys up in this little room and say, “No matter who opens the door, keep playing. I got permission to rehearse here.”

So we’re playing and at the appointed time the door opens and it’s Bing. He stands there a minute, apologizes and then leaves. A moment later, the door opens again and Bing asks, “What do you guys call yourselves?” I say, “The Les Paul Trio.” Bing says, “Working?” I say, “NBC.” He says, “Not anymore. You’re working for me starting next week.”

DM: And you continued to play with Crosby, off and on, throughout the rest of his career, didn’t you? Something like 35 years?

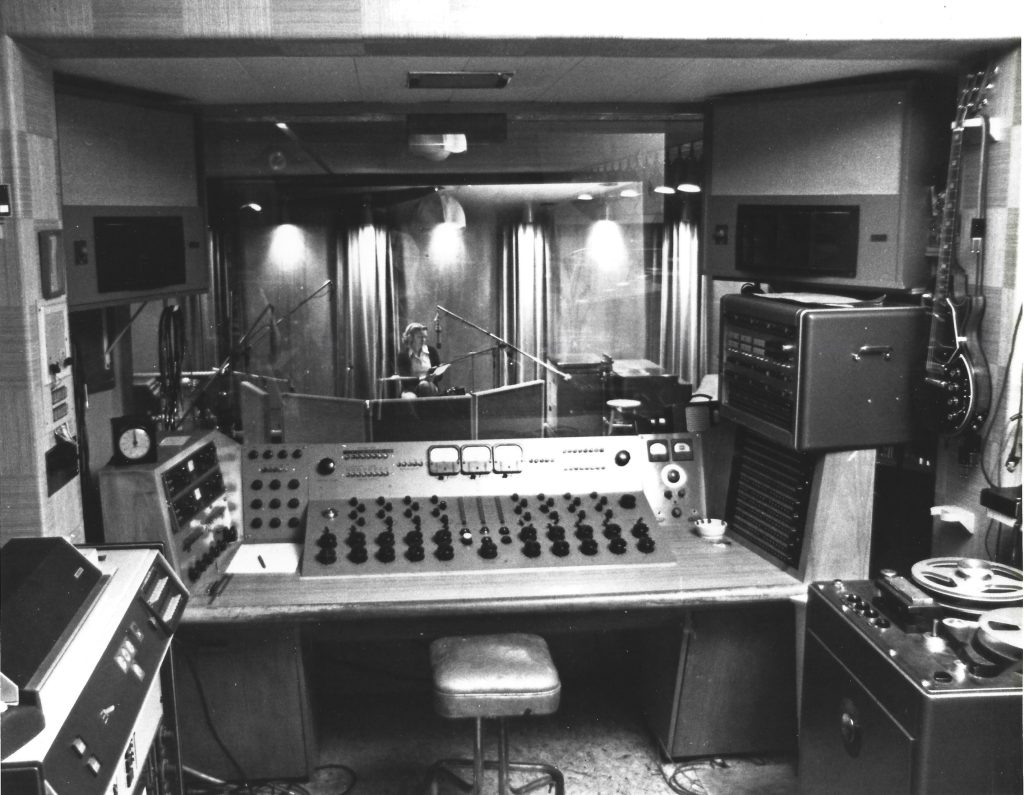

LP: Right up to his last record, I think. He was a dear friend, and you know, he was responsible for me building my recording studio. …

DM: How so?

LP: Well, he drove me all over town looking for a building to build a recording studio in, but I told him I wasn’t interested. Later, I met my buddies and they said, “We could do it right here,” and wouldn’t you know it, within three days we were building a studio in my garage in Hollywood.

And it wasn’t long after that that we started recording the Andrews Sisters, Art Tatum, Jo Stafford, Kay Starr, all kinds of people. Even W.C. Fields.

DM: Okay, so now, I’m assuming this is where multitrack recording came about. Can you tell me how that happened?

LP: It was born out of something my mother had said. We had gotten together one afternoon and she said to me, “I heard you last night on the radio.” I said, “That wasn’t me. I was onstage with the Andrews Sisters last night. … It was probably somebody else trying to sound like me.”

And she says, “If your own mother can’t tell if it’s you or not on the radio, you had better stop sounding like yourself.”

I said, “Ma, I can’t stop people from copying what I’m doing.” And then she let me have it. She said, “Well, if I can’t tell you from the next guy, then you just don’t mean anything.”

DM: Wow.

LP: Wow is right. So I gave my notice to the Andrews Sisters, who I was playing with when I wasn’t busy with Crosby or some other thing, and I locked myself away in the studio. All sorts of people came by and tried to get me back out on the road, but I told them I was looking for something new and different and finally I came up with this sound.

In fact, that’s it right there …

[By this time, the series of interviews with Les Paul had moved to his Mahwah, New Jersey, home. The house itself was unusual. From the outside, it looked like an architect’s idea of a Space Age accommodation from a very grounded, 1950s perspective.

Inside the house was furnished in a mid-20th century modern style, with clocks and appliances embossed with pastel colors and metalized plastic trim simulating chrome. What made the environment truly Les Paul’s however, were the multitude of guitars strewn just about everywhere.

As we struggled to find a space to sit, eventually pulling tall chairs up to the counter separating the kitchen and living room, Paul estimated he had as many as 400 of his signature guitars in the house. In little bowls on the countertop were little pieces of electronics. Stuck to the front of his turquoise refrigerator was one of those “Hi my name is” stickers signed by Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page.

But what Les Paul was referring to was a tall, rectangular metallic structure standing in center of his living room, covered with knobs, close inspection revealed the very robotic-looking piece of “artwork” was actually a series of Ampex reel-to-reel tape recorders, one stacked on top of the other.]

DM: [Reaching out, touching the stack] This is …

LP: The first multitrack machine, and the console that marries to it, the first sound-on-sound recorder; the first of all the things I was involved in. …

DM: It’s amazing to be standing so close to history.

LP: There is a lot of history there and it’s all headed to the Smithsonian Institution.

The problem is, it can’t stay here and be in Washington at the same time, so it has to come out and you’ve got to put it someplace while it awaits shipment. … So we put it here in the living room.

DM: Sounds like a big endeavor to get everything out and ready to move.

LP: At this point, only a hand grenade could straighten it all out.

There is one touchy little issue, however, and it’s that, while these things might be on display in a museum for two or three years, there’s a possibility that they’ll be removed for another exhibit and wind up in storage for the next five years or more.

So what I said was, I’ll get a lease on it. And when it leaves the public display, it’ll come back here. I don’t want it going to some warehouse in Baltimore. I don’t want the thing to go to sleep in somebody’s warehouse or basement.

The other difficult part about putting all these things in a museum is that they’re all custom or homemade, so nobody knows what the hell it is unless I identify it. They’d say, “Is this that machine or this machine?” And only I know. [Laughs]

DM: So was it hard for you, in an emotional sense, to disassemble everything so that it could be carted off for the public to see?

LP: Well, I’ve lived in this house since 1951 and I’ve had my workshop set up this entire time and for years and years, everything was immaculate … everything was in order … and it didn’t get out of order until 1980, ‘81, when I had my heart surgery. It was after that I couldn’t possibly take care of it the way I used to. ….

DM: So where did you get these tape machines?

LP: Well, again, this goes back to Bing Crosby. He had commissioned the Ampex Corporation to produce the first tape recorder, based on a prototype the Germans had created during the war. Crosby gave me the first model that Ampex came up with, and I ordered a second recording head, parting them to come up with the sound-on-sound tape machine.

Ultimately, I recorded 22 sides with multiple overdubbed guitars and carried them under my arm over to Capitol Records.

I played a few of them and started packing up and the guy said, “Hold it right there, Les, we’ve got a deal to work out.” And we came to an agreement for a string of Capitol releases right then and there. In fact, I think we wrote it out on the back of one of the envelopes I’d brought the records in.

The first one they released was “Lover,” backed by Brazil, and it was a big hit. It was also the first time I was able to combine all my inventions and recording techniques into one bag of tricks.

Nobody knew what I was up to in the studio all that time, and when I came out, I hit them with everything at once: delay, echo, reverb, flanging, you name it.

DM: Speaking of other people you’ve played with, how was it that you came to play with Louis Armstrong?

LP: Well, I had begun moving about. I’d gone from Waukesha to Springfield, Missouri, to St. Louis, to Chicago. Just playing different venues, different gigs with different people. In fact, it was the end of a tour, and there was a fellow in Chicago called Eddie South, and he was known as the Dark Angel of the Violin. He was classically trained, but had been heavily influenced by jazz during a stay in Europe.

So when he got back to Chicago, which was kind of his home base, he started auditioning guitar players, looking for a guy that could play jazz. Now, Eddie was a great, great violin player, so this was quite the opportunity, and when he heard me play, he said, “That’s it. You’re the guy.”

So we ended up playing at the Regal Theater on the South Side of Chicago. It was one of those situations where we would do our act and then, after we got off, another band would come on.

This one night, as we’re walking off, I hear this guy playing [imitates an ascending trumpet line], but just as he gets to the last note, he misses it. He says to the audience, “Well, I guess my chops aren’t together, I’m going to go after that one again.” He must have done this five times and he missed it every single time.

By this point, the crowd was hysterical and rooting for him to get it and he was determined to reach a note even higher. I remember turning to Eddie South and asking, “Eddie, who is this guy?” And he said, “I don’t know.” I asked people backstage and nobody knew who he was, so I went out front, to the marquee, and there, in relatively small type, was the name “Louis Armstrong.”

So I went back in and when he came off stage, I walked over and introduced myself and after that, we became friends. He was a wonderful man. It was a great privilege to be a friend of Louis Armstrong.

DM: Now, we met for the first time, just the other night at Fat Tuesday’s, and you seemed really intent on convincing the audience that you’ve retired. But you play every week, so aren’t you stretching the definition of retirement a little bit?

LP: Oh no, I really am retired. I retired in 1965. I gave it up, hung it up on the wall.

DM: Can I ask you about Mary Ford?

LP: Absolutely.

DM: She was such an integral part of the sound, as well as the act when it really got rolling in the 1950s. …

LP: The planet is very large and on this planet there was only one Mary Ford and I found her … or she found me. She was kind of a guitar hippie, though they didn’t use that term then. She followed me from club to club. I’d be backstage and ask if she was out front and they’d say, “Yep.”

And this went on for something like five years, at a time when I’m auditioning all kinds of female singers, people like Doris Day and Rosemary Clooney, and the whole time, the voice I needed and the partner I needed was Mary, and I didn’t know it.

Anyway, I picked Doris Day as the girl who was going to be my singer.

At the last minute I backed out and said, “No, I don’t think so.” And Mary said, “What are you going to do, sit up there, sing and play tambourine?”

I figured I needed to think of somebody, somewhere. But, it never got to me until later, when one night I was playing at my brother’s and father’s tavern and my brother forgot to hire a bass player. Mary had been following me around for five years.

I told her that she should know what I play so she could play. I’m not playing up there alone! It was then and there that I decided I’d have Mary sing something. She sang church songs and a couple of hillbilly songs. So, I got her doing that and that’s when the light lit!

I turned to my dad and he was shaking his head, “No!” and I was shaking my head, “Yes!”

My dad felt that I was a roughneck and she was delicate by comparison, and he said, you two will never make it together! We did. We met in 1945 and we married the day before New Year’s, the last day of 1949.

And when you think about it, it really is remarkable that on a planet this large I could find somebody who was not only immensely talented, but could hear what I heard and happened to have the same talent I had, it’s a miracle.

Of course today, I know a majority of people out there don’t realize what a genuine talent she was, but she was really, really great.

DM: Did you go home to Waukesha to debut the act?

LP: We did, it was right before the accident.

DM: Now that’s a remarkable story.

LP: Well, it was an unusual set of circumstances in the first place. Ordinarily I would have been driving, it being January [1949] and ice and snow being a possibility, but I had been sick with a fever for several days and Mary drove to let me rest up.

So we’re driving on Route 66, and get just west of Davenport, Oklahoma, where we run smack into the worst winter storm you’ve ever seen. My eyes were closed and suddenly I hear Mary scream and felt the car swerve and the next thing I know, we’re going over the side of a railroad overpass and dropping into a ravine.

The last thing I remember is turning toward Mary and saying, “This is it,” while reaching to cover her face.

[Because Paul and Ford were driving in a Buick convertible, they, and all their equipment and any luggage that wasn’t in the trunk, tore through the car’s canvas roof as it plunged 20 feet into the ravine.

Mary Ford was not seriously hurt. Les Paul, however, was a mess when the car finally came to rest, upside-down, in an icy river. All told he came out of the accident with six broken ribs, a fractured pelvis, broken vertebrae, a punctured spleen, a broken nose, and a deeply bruised collarbone and shoulder.

The worst of his injuries, however, occurred to his right arm, the one he shielded Ford with, which had shattered like a piece of China, and his elbow, which was completely crushed.

Trapped in their car, because of the storm, the couple was forced to wait nearly eight hours before help arrived. When it did, it came in the form of a telephone work crew that had been sent out to repair damage to a downed line.]

So I’m lying there in the hospital [Wesley Presbyterian Hospital] really a mess, and there was a question of whether I was even going to make it. And finally, when they thought I was stable and coherent enough to understand, they come in and say, there’s nothing we can do for your elbow, it’s as shattered as can be and can’t be rebuilt.

“Okay so what does that mean?” I ask. And they say, “The only other option is amputation.”

So basically, I’m being told I’m never going to play the guitar again, which was not an option for me. I put everything on hold until I was well enough to get to Los Angeles, where my doctor says he’ll do everything he can to save my arm.

He comes up with the plan to replace my right elbow with a piece of bone from my leg. The catch is because I wouldn’t have an elbow joint, my arm would stay set in whatever position he set it in.

I said to the doctor, listen, when you set it, put my forefinger in my belly button. That’s how I hold the guitar, and I’ll still be able to play.

[Paul’s doctor was unconvinced. The damage was so severe, no one but Les believed he would ever pay again. Even Les had his moments of doubt. During those moments, working in his hospital bed, he began to draw up plans for yet another investigation, a guitar synthesizer that could be played with one hand.]

So they set my arm at about a 90-degree angle, which was great because I could cradle the guitar and pick the strings, but I still had a long time to think about it. I was in the hospital for almost a year, and then it was another several months before I was considered sufficiently recovered enough to try to play.

During this time, I changed the whole concept of what Mary and I were doing, created a whole new kind of music, actually. So being disabled like that gave me time to reassess what we were doing and forced me to stop doing things the way I’d done them before the accident.

DM: That’s an absolutely harrowing story.

LP: Oh, it was something to go through, let me tell you. It was one of those situations, initially, where if you moved anything, you were dead.

DM: On an entirely different note, and maybe to lighten the mood, I once heard somewhere that Mary wasn’t originally too taken with the Les Paul guitar.

LP: That’s actually true. You see it took Gibson a while to get it right. Which you expect when you’re preparing to put out a dramatically new product.

They made a series of prototypes, maybe three or four, and once they got it right, I really liked it, but Mary didn’t.

She said, “I’m just not going to play this thing.” She thought it was weird, “too tiny” in her words.

And that’s because she was used to these great big, massive hollow-body guitars and I was used to these narrower instruments.

But in any event, she was really concerned about the difference in the overall size of the guitar, and also about its weight … because it was heavier than your typical acoustic.

I didn’t care about any of that. All I was concerned about was the end result. I didn’t care if it weighed 200 pounds, I could always just sit down and hold it on my lap.

DM: So this is just a hobby now?

LP: It’s a hobby, but what a hell of a hobby. Holy mackerel. [laughs] I’m working harder now than when Mary [Ford] and I were rolling. It seems like it anyway.

What happened was, I was in the hospital, this is in 1981, having quintuple-bypass heart bypass surgery. It was one of those times in life when you seriously ask yourself, what would I like to do with the time I have left.

On top of this, I was suffering from what the doctors called an acute arthritic condition, which basically crippled two fingers on the hand I used on the fretboard, and four fingers on my strumming hand.

In fact, it was the onset of arthritis that caused me to hang it up in the first place.

So here I am in the hospital, laid up, and I’m thinking, I don’t know how long I’m going to live with these bypasses. And then, thinking my time could be short, I ask myself, “When did I have the best times of my life, the most fun?”

And what showed up was playing in a nightclub, dealing with an audience on a one-to-one basis. From there, I determined that should I try it, the club would have to be small and I didn’t want whatever I did to be perceived as a comeback. I just wanted to be with people.

Then I went to the people at Fat Tuesday’s and I said, “I’d like to play here Monday nights.” They said, “But we’re not open Monday nights.” So we talked and I finally convinced them to give me a two-week tryout. And as we speak, it’s been four years since this all got started again.

Knowing you have something like heart disease makes you think about how lucky you are. It makes you appreciate being able to get out there and perform, to feel good doing it and make other people happy.

DM: One thing I noticed the other night was this kind of, I don’t know …. cat and mouse game … that was going on between you and the other members of the trio.

LP: That’s right! And that’s part of the fun. I mean, we’ll start out with something like “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and then as we get to the bridge, I’ll switch to “You Took Advantage of Me” or “The Best Things In Life Are Free.” And then for the next four bars it’ll be another song and so on. …

The band doesn’t know what bridge is coming and the audience is cracking up and we’ll just go along like that like a bat out of hell. And right in the middle of it, as we’re going around this hairpin turn, I’ll say to Lou, “Hey, why don’t you sing a little something?” And he’ll go, “Now? Are you crazy?” It’s all part of the fun.

DM: These days a lot of young players come down to Fat Tuesday’s to play with you. What do you think they come away with from that experience?

LP: Well, you’d have to ask them, but what they tell me … well, I’ll give you an example. Mark Knopfler [of Dire Straits] was down here recently and he called me up afterwards and said, “Les, I don’t want to see you for another six years because it will take me that long to learn to do the things I saw you do the other night.”

DM: A nice compliment. What do you get out of playing with them?

LP: Oh, I love it. I get all kinds of enjoyment out of playing with them. Jimmy Page will fly over, he’s a dear friend, Jeff Beck, another dear friend, will fly over — just to hang out and play and they play better than I do!

Rick Derringer, George Benson, Eddie Van Halen — I love him. He worships me and I worship him. It’s a real privilege to have guys like that come and play with me. There’s a lot of great musicians out there.

Hey, did I ever tell you my story about Jimi Hendrix?

DM: No, I don’t think you have. …

LP: Well, this was in about 1962. I was driving up Route 46 in New Jersey, taking a master to Columbia Records in New York. So I stopped in this little restaurant and they’re auditioning this kid for a job and he’s pretty darned good. I said to the bartender, “I’d like to talk to that kid, but I can’t now. I’ll be back in a little over an hour or so.” But by the time I came back, the kid was gone.

The bartender tells me, “We threw him out. After a while he just played too loud and at one point he started banging on the piano.” I said, “Oh, I think you made a mistake, I thought he was great.”

So, I went around to every small club I could think of in New Jersey and New York City, and I can’t find him. I leave word, “If this kid with longish hair and a left-handed guitar comes in, give him my number.” Well, none of this effort comes to anything. I never found him.

So then, shortly after I retired, I got a call from London Records, and they asked me to just make one more album before I quit. Finally, I say, “Okay, but only on the condition that you send me a bunch of records by the young guitar players who are popular now, so I can see what the scene is and so forth.”

Well, they lay a bunch of albums on me and one of them is “Are You Experienced?” by the Jimi Hendrix Experience, and I looked at the photo on the cover and I said, “God damn, there’s the kid I’ve been looking for. He’s been over there!”

DM: Did you ever actually meet?

LP: Oh sure, and when I told him that story, he just cracked up. Of course, by then, he was a big deal, so the missed opportunity, for want of a better term, didn’t bother him. And I think we last spoke when he came out with the “Electric Ladyland” album. He called me up to tell me all about it.

But it’s like I said earlier, I try to stay aware of what’s going on. And that’s how my friendship with Jimmy Page started. I saw him very early on, when Led Zeppelin played their first concerts over here.

DM: So if a kid came up to you today and asked what attributes he would need to join the ranks of these great guitarists, what would you tell them?

LP: I would tell them before you beat your head up against the wall, make sure that God gave you all the necessary things.

Now these are — and you might want them, but you can’t buy them at the Sam Ash music store — a good ear, by which I mean perfect pitch or damn near close to it. Second, you can’t buy rhythm. It’s a God-given talent, if you believe in God. Otherwise, it’s just a gift.

The next thing you better have is the ability to create some things. You should have a great ability to do that. You must also have the want. And by that I mean, you’ve got to want it so badly that you’ll be willing to put the time in when another guy is having a ball with some chick or something.

There are a lot of temptations to steer you away from it, so you’ve got to be very energetic and dedicated.

There are several more that I can name, but one more that’s very important is mixing. After you have all the techniques down, you have to take all these notes and put them in the right places.

[The drummer and bandleader] Buddy Rich and I used to talk about this all the time, and I think we both agreed the most important thing of all is what you do with what you’ve got.

DM: It’s a daunting list.

LP: Well, let me give you one more. Another gift is the ability to recognize what the public wants. Most people get carried away with trying to impress other musicians, which I don’t try to do at all. I’m not here to do that. I’m there to play what the majority of people come to hear.

That’s terribly important because if anybody says, “Look, I am a musician, not an entertainer,” he’s a fool. You are entertaining, so it’s terribly important that you get that message across with your hands, through your instrument.

You tell them just exactly what you want them to know when you play. A lot of people just run off a lot of notes, but what’s really impressive is when you can communicate, without words, to someone in the audience.

I mean, the simple example would be if you get a girl in the front row and you play a song and it makes her say, “Yes, I would like to get together later.” You know, that kind of communication.

Or it can simply be saying to someone or a party at a table, congratulations, I’m happy for you. That, I think, is what a young kid sees when he comes down to Fat Tuesday’s and I think that’s what impresses him, far more than technique. You see that you can relax onstage and tie a message to what you’re playing.

DM: Right.

LP: And one more thing …

DM: [Laughs]

LP: You’ve got to remember, you only learn if you’re looking and listening; otherwise you can be with someone for 10 years and you just get dumber.

DM: This might sound like one of those trite, “reporterly” questions, but I really am curious about your response. What does the guitar represent to Les Paul?

LP: Well … it’s a housewife, it’s a psychiatrist, it does a lot of the things … for instance, if I was under some kind of strain or was totally confused, whatever it was, the first thing I would do is go over and pick up a guitar and start to pick on it, and through that, solve my problem.

I think it works great in that regard. It’s a great bartender in that way. It’s different from a dog, but it’s a friend. It’s a way of transmitting your feelings to the public. You can say a lot with it.

Dan can be reached at [email protected] and @DanMcCue