Scientists Set Record for Fusion-Generated Energy

OXFORDSHIRE, U.K. — Researchers at a joint European testing facility set a record for the amount of energy generated from the process of nuclear fusion, but experts say machines capable of safely supplying that energy to the grid are still decades away.

The breakthrough, announced on Thursday, occurred in December at the Joint European Torus facility located at the Culham Centre for Fusion Energy in Oxfordshire, which is located about 56 miles northwest of London.

The facility is set to be decommissioned later this year, and the experiment was to be the researchers’ last on the current equipment.

On their final try, the team of scientists generated 69 megajoules from a sustained fusion reaction lasting five seconds, easily surpassing their previous record of 59 megajoules set in 2021.

“JET’s final fusion experiment is a fitting swan song after all the groundbreaking work that has gone into the project since the early 1980s,” said Andrew Bowie, U.K. Minister for Nuclear and Networks.

“The work doesn’t stop here. Our Fusion Futures program has committed £650 million to invest in research and facilities, cementing the U.K.’s position as a global fusion hub,” Bowie said.

The downside of December’s experiment was that it consumed far more power than the fusion reaction produced. To make fusion a viable low-carbon energy option, they’ll next have to determine how to keep the fusion reactions going longer.

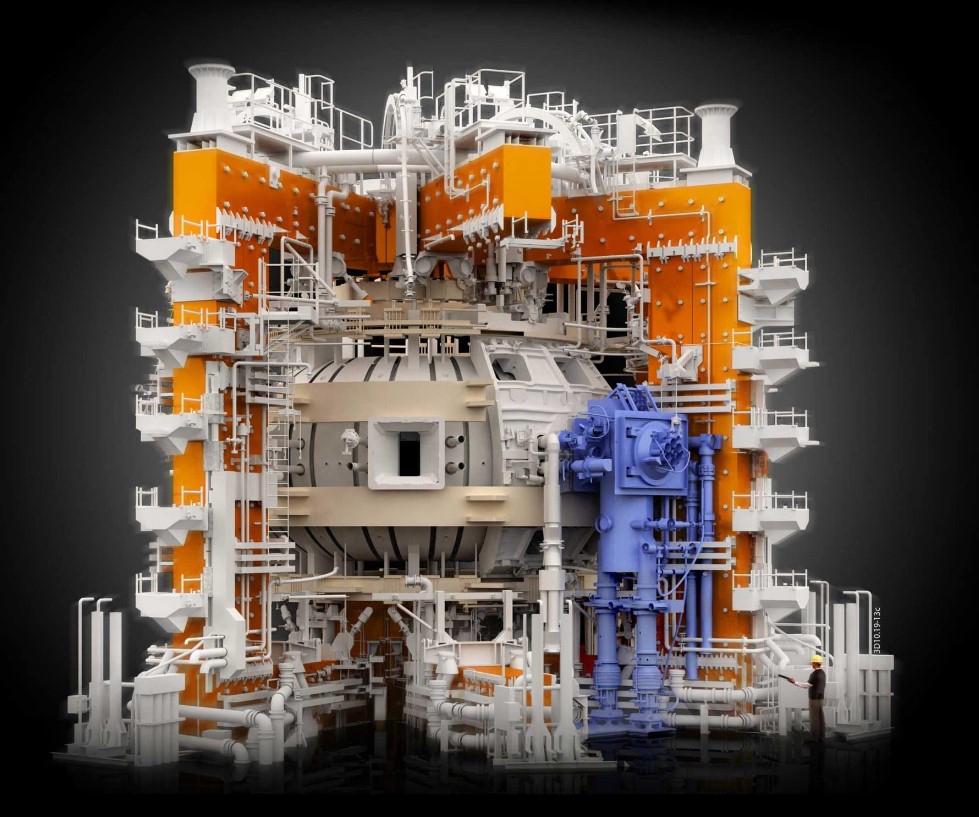

And that will have to wait until the Joint European Torus facility is replaced by a new facility, to be known as the Spherical Tokamak for Energy Production project.

The project, being built under the auspices of the British government, is currently being built on the site of a decommissioned coal-fired power plant in Nottinghamshire, U.K.

If all goes according to plan, officials believe the Spherical Tokamak facility will become one of the first fusion machines anywhere to supply power to the grid, likely sometime in the early 2040s.

“Tokamak” is the name of a design developed by soviet scientists in the 1950s. It relies on powerful magnets to hold a plasma of hydrogen isotopes in place as it is heated to temperatures surpassing those of the sun.

As the temperatures peak, the atomic nuclei in the plasma fuse, releasing energy.

The Joint European Torus facility was a collaboration between the United Kingdom and its former European Union member partner, Switzerland, and Ukraine.

“JET has operated as close to powerplant conditions as is possible with today’s facilities, and its legacy will be pervasive in all future power plants. It has a critical role in bringing us closer to a safe and sustainable future,” said professor Ian Chapman, CEO of the U.K. Atomic Energy Authority.

“JET’s research findings have critical implications not only for ITER — a fusion research mega-project being built in the south of France — but also for the U.K.’s STEP prototype power plant, Europe’s demonstration power plant, DEMO, and other global fusion projects, pursuing a future of safe, low-carbon and sustainable energy,” he said.

Since becoming operational in 1983, the facility has been the most powerful Tokamak-style machine on the planet, and it has been setting successive records for energy output since 1997.

Advocates for fusion insist the reaction could become an inexhaustible source of clean energy, with the added benefit of producing no long-lasting radioactive waste (a problem with the fission relied on by nuclear power plants, which harness the energy produced by splitting atoms).

Fusion backers also argue that the process would largely resolve energy supply chain issues because the necessary isotopes can be readily sourced in large quantities and that only small amounts of material are needed to produce enormous amounts of power.

Over 300 scientists and engineers from EUROfusion — a consortium of researchers across Europe — contributed to the experiments carried out in Oxfordshire.

“Beyond setting a new record, we achieved things we’ve never done before and deepened our understanding of fusion physics,” said professor Ambrogio Fasoli, EUROfusion’s CEO, adding the work showcased “the unparalleled dedication and effectiveness of the international team at [the facility].”

The team is expected to assemble for a final time later this month, to honor the founding vision behind the decommissioned facility and celebrate its legacy of successes.

Dan can be reached at [email protected] and @DanMcCue