Here but Not Here: The Forgotten Legacy of Newspaper Row

WASHINGTON — In early December 1927, the last vestiges of an old Washington, D.C., neighborhood collapsed into rubble.

Newspaper Row, as it was called by those who worked there, came into being before the Civil War, and in its glory it encompassed 11 structures, the vast majority of them small, two-story “shacks” as their inhabitants called them, running along the east side of 14th Street, and stretching up the hill from Pennsylvania Avenue to F Street.

But just six months after Charles Lindbergh’s successful solo flight across the Atlantic, during the week after Thanksgiving, the six remaining buildings, opposite the “new” Willard Hotel, were hastily cleared.

Appropriately, the last of the ramshackle buildings razed to make way for a modern office building was the one-time Western Union telegraph office, the reason newspapers crowded the neighborhood in the first place.

Back then, you see, the White House, which was just a stone’s throw away, wasn’t considered much of a beat. It was home to a single leader and an administration hopefully speaking in one voice. It was managed. It was controlled.

By comparison, Capitol Hill was contested territory. A battleground. Open. Chaotic. It was the place to be if you wanted excitement and not a little bit of controversy.

For the first 150 years of the Republic, as Donald A. Ritchie wrote in the “Press Gallery,” his history of the Washington correspondents, the Capitol, rather than the presidency, was the epicenter of Washington journalism.

But you had to get your news out and get it out quickly, and that necessitated proximity to the old telegraph office.

To walk the row in the 21st century, nearly 100 years after it gasped its last breath, it’s hard to imagine the huge crowds that once gathered by gaslight late at night when big breaking stories from other parts of the land came in over the telegraph or the rabble-rousing corps of Washington correspondents in whose ghostly footsteps one strides.

Aside from the National Press Club, a 13-story edifice largely indistinguishable from any other D.C. office building, there is truly not a hint of what came before.

Walking north from Pennsylvania Avenue, one passes the JW Marriott Washington Hotel, a liquor store and a sandwich-board sign advertising Hugo’s barber shop as “the best barber shop in DC” before coming to the northernmost limit of the old row, now dominated by a corner sandwich shop.

No historic marker recalls what once transpired here, and such is the city’s neglect, that an email from The Well News asking the district planning department why, did not even receive a response.

A Neighborhood of Scribes Coalesces

Correspondents had been a fixture in Washington from almost the moment it became the capital of the Republic.

However, there was no “central nexus” for the work until a fledgling, if ambitious, new company, Western Union, decided to open a telegraph station near the corner of 14th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue NW.

Up to this point, the emerging technology of the electronic telegraph had been the province of regional monopolies, which Western Union had steadily snapped up over the previous decade.

In all likelihood, Western Union’s choice of location in Washington had less to do with being near the seat of federal power than with its initial proximity to the headquarters of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, which was just up the street.

Though point-to-point communication of telegram and other messages would be Western Union’s core business, the nation’s emerging railway companies were also steady customers, as they relied on the telegraph as part of their primitive train control systems, using quickly hammered out texts to reduce the chances of train collisions.

The first newspaper to maintain an office on what would soon become Newspaper Row was the New York Herald, a paper founded just 15 years earlier by James Gordon Bennett, a Scottish immigrant.

From the start of his paper, which for a time years later would be the highest-circulation newspaper in America, Bennett was an innovator.

In 1836, he joined other publishers in printing the lurid details of the murder of a prostitute, Helen Jewett, and the trial of her accused murderer, on the front page of his newspaper.

It was one of the first sex scandals to receive a thorough going-over by the press, and when the accused, a 19-year-old man named Richard Robinson, was acquitted of the murder, it became a bona fide stunner.

Throughout the trial, Bennett distinguished the Herald by featuring the most detailed coverage of the case, and he came away from it reputed to have published the first ever “journalistic” interview, getting an exclusive with Rosina Townsend, the brothel keeper who discovered the slain woman’s body.

Though some would later claim the interview was a hoax, Bennett continued to be an innovator. He initiated the cash-in-advance policy for advertisers, which later became the industry standard, and he was among the first publishers to run illustrations with his stories, beginning with a series of woodcuts.

When he first dipped a toe into the Washington, D.C., market, he did so in equally splashy fashion, conducting the first exclusive interview with a sitting president, Martin Van Buren.

It was shortly thereafter that the Herald took up residence on Newspaper Row, with a young reporter named W.B. Shaw being named the paper’s chief — in reality, its only — Washington correspondent.

One day while Bennett was making a personal visit to the district, he and Shaw got into a lengthy conversation on ways to distinguish the Herald’s Washington coverage from that of its competitors.

Shaw seized the opportunity to unburden himself. Like other reporters in town, Shaw filed his daily budget of Washington stories by mail, which was slow and unreliable. Even under the best of conditions sending dispatches to New York required him to catch the early morning mail and then hope his stories arrived at the paper by nightfall.

“Why not bulletin the major events of the day by telegraph?” Shaw asked at one point.

Bennett was taken aback.

“Why, it costs 10 cents a word to send a message by wire,” the publisher replied, adding that it was the prohibitive cost that had kept other newspapers from doing it in the past.

Shaw was undeterred, believing the early arrival of breaking news from Washington would give the Herald a decided edge in New York, an edge that would pay off in growing numbers of readers.

“I think it would pay,” he said in the face of his boss’s intransigence.

Then Shaw had a brainstorm.

As he explained to Bennett, “I could cut out the “a’s, and the “the’s” and all superfluous words, defraying the cost considerably.”

“Well, you may try it,” Bennett said. With that, the “telegraphic” correspondent was born, and quickly, other papers began to follow suit, setting up shop as near as possible to the Western Union office.

Day or Night, Denizens of the ‘Row’ Were Hungry for News

At this point, the “row” was a haphazard assembly of two-story frame and brick buildings on a street that one longtime denizen described as “nothing but mudholes.”

“Street cars were drawn by horses. We knew no such thing as paving,” he said.

How much room an individual newspaper occupied was entirely dictated by its level of success and the ambitions of its publisher.

Bennett’s rival, Horace Greeley, for instance, filled an entire small building on 14th Street with the New York Tribune’s operation. Henry Raymond of The New York Times, meanwhile, had his modest D.C. staff housed in the back of an alley, about where the back of the Marriott hotel lobby is today.

The Boston Advertiser soon had an office next door to the Times, and so it went, with papers so cramming the row by the Civil War that newcomers were forced to lease desk space from their more lucrative competitors.

A typical newspaper bureau consisted of a small anteroom, a larger reading room, a reporter’s room and a private office for the chief correspondent. But “private” can only be loosely applied here.

In reality, late night visitors — including senators and congressmen, prominent officials and business people — all routinely beat a path to these rooms to share secrets and tips, and to get the latest news.

To minimize the crush and interference of these visitors, the telegraph office and nearly all the papers hung boards outside their establishments on which they posted the latest headlines.

While this worked in terms of routine crowd control, election nights were another matter.

According to one account, published in The Boston Globe in 1872, “these self-elected ‘friends’ of the correspondents,” turned out en masse to await the returns, “conceiving it to be their inalienable right to break furniture, defile the floors, talk loud and ask innumerable questions.”

Providing the fuel for such antics — both on the part of visitors and reporters — was the proximity of “Rum Street,” a row of speakeasies located just a block away on E Street.

Despite the inevitable rivalries between papers and competitive nature of the work, the reporters and correspondents soon began to think of themselves as a fraternity or brotherhood — working side by side by day and drinking side by side by night.

In an anonymous critique piece, attributed to one “Max,” the Chicago News reported on June 14, 1885, that “generally, Washington reporters are plants of Washington growth.”

“Originally department or committee clerks or literary blacksmiths of one sort or another, they pick up a little newspaper work here and there and make useful acquaintances, and by-and-by they drop into a soft job as a correspondent for a paper of consequence, and from that time on they have an easy life,” the paper said.

“If they get fired from one paper, they have two, three or more smaller papers to fall back upon until they succeed in making other good connections.

“To lighten their labors, the old-timers form themselves into sets or combinations. These combinations are curious institutions,” Max wrote. “Original copy is traded back and forth. The budgets made up and forwarded form dreary reading. Pirated matter is infinitely preferable.

“These wonderful bureaus make a point to send no news whatsoever,” the critique continued. “They circulate essays and matter calculated to educate the nation in statesmanship. These combinations blight and discourage enterprise. They are formed and held together, not for the purpose of getting news, but to keep from getting scooped.

“So long as no rival papers are getting news they are perfectly content to get nothing themselves, and as a consequence enterprise in the news field here has long since been killed. It died of inanition.”

But Max went on to offer an interesting assessment of the individual papers populating the row, and how they went about their business.

“The only competition is among New York correspondents. They dig out the only news sent out from Washington,” he said.

“The Sun has the best service, and besides its regular correspondent pays five or six special writers handsomely for news furnished. In this way the field is well covered,” Max continued. “The Herald pays liberally for news and occasionally gets in a good piece of work.

“The Tribune and Times run to statesmanship largely. The World is not paying much attention to routine Washington news. The Boston Evening Traveller, Cincinnati Enquirer, Baltimore Sun and Philadelphia Press have excellent talent on the ground here.

“The Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, Boston Herald, Chicago Tribune and St. Louis Globe-Democrat are paralyzed by bureau work,” he said.

“The ways of the Washington correspondent are unlike the ways of newspaper writers anywhere else in America,” added Max. “The veterans in the Washington newspaper field detest newcomers.

“They do not like the brief season of enforced activity that always follows the advent of a new arrival,” he said. “A ‘fresh’ man brings with him the uncomfortable consciousness that he owes a duty to his employers, and that he is expected to render value received for the money that is paid him.

“If he is made of common stuff he soon gets over such foolish notions, and when he does, the veterans take him into full fellowship,” he added.

While this sense of fellowship and camaraderie would eventually lead, among other things, to the founding of a formal press club, it also had a few less noble attributes. Among these was the “blacksheet,” as when reporters traded carbon copies of their stories to help cover for drunk, missing or otherwise indisposed colleagues.

Many reporters on the row found it hard to leave the neighborhood, even on days when they got their copy in early, believing that if they waited long enough, something else would turn up.

The better paid correspondents felt the same way, often choosing to join politicians and lobbyists in nearby restaurants or other settings to engage in the trade of gossip that seemed to grease the skids of the town, even then.

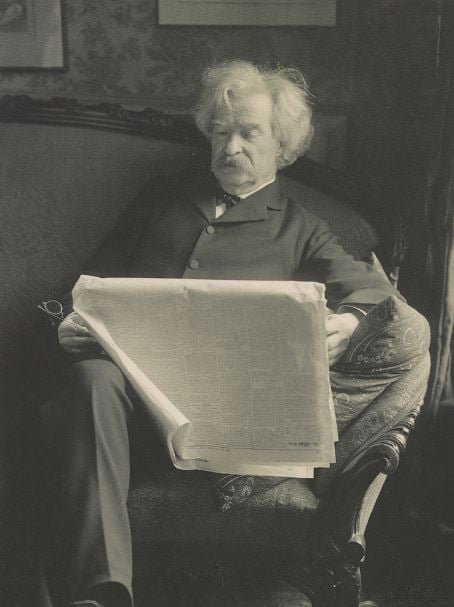

Among those who made their way to the row for work, was a young Mark Twain.

Still known simply as Samuel Clemens, the future author lived in a boarding house just off the row and is said to have even spent a few nights crashing in one of the rooms at the Tribune office.

His brief stay in the city, lasting just six months, beginning in November 1867, illustrates the entangled relationship many in the press had with “official” Washington at the time.

Clemens was not only a newspaper correspondent covering the 40th Congress, he was also personal secretary to Nevada Sens. William Stewart and Joseph Nye.

At the time, many other journalists took advantage of the largely unregulated environment they worked in to lobby causes, sell their hot tips and collect patronage.

In an 1883 article in the Philadelphia Press, columnist Hiram Ramsdell observed that Twain was a surly visitor and not always welcome on Newspaper Row.

“He was never good-natured, and was sometimes absolutely offensive, so much so that the correspondents did not always like to see him about,” Ramsdell wrote.

For his part, though he is said to have attended a lavish party here and there, partaking of the alcoholic refreshments, Clemens saw Washington itself as dull, and fitted out with bad weather and worse restaurants.

“Am hobnobbing with these old generals and senators and other humbugs for no good purpose,” he wrote in a letter home.

Among those generals was Ulysses S. Grant, though it’s likely Clemens met him as a result of his senatorial staff job and not as a newspaperman.

In his spare time, and sometimes, even while covering hearings in the Senate chamber of the Capitol, Clemens worked steadily on his first book, “The Innocents Abroad.”

“I am most infernally tired of Washington and its ‘attractions,’” Clemens wrote his brother as he packed to leave in the spring of 1868.

But where Twain wilted, others thrived.

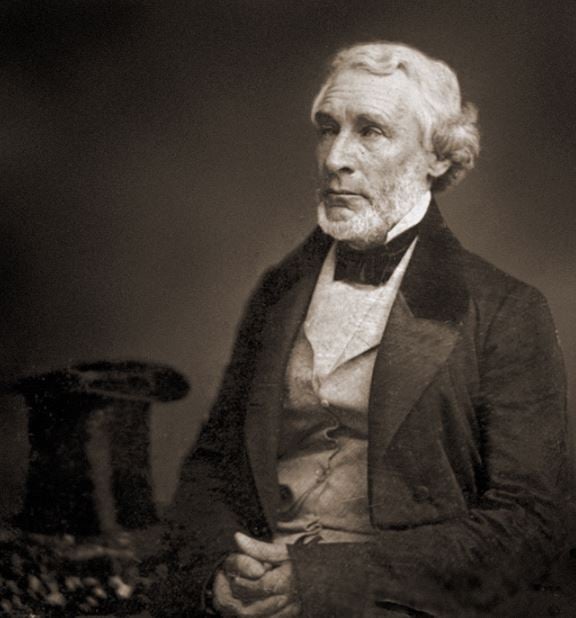

Among these was a correspondent from Massachusetts named Benjamin Perley Poore, who used the somewhat strange byline Ben: Perley Poore.

Like Twain, Poore would acknowledge that Washington could seem an “overcrowded and inelegant city,” full of “contractors, office seekers, confidence men and courtesans.”

But where Twain couldn’t wait to get out, Poore saw opportunity and seized it.

He is said to have loved nothing more than spending his evenings on Newspaper Row, writing his dispatches until about midnight while meeting with a steady stream of lawmakers who would supply him with recaps of the day and the latest gossip.

His ability to take inside information his contacts gave him and mold it to match the interest of readers, made him one of the most popular and prolific journalists of his era.

Such was his reputation that when he died in May 1887, The New York Times recalled that he “had a wide acquaintance, having known everybody of consequence in the capital for 30 years or more, was a living storehouse of anecdotes, a popular diner-out and enjoyed the confidence of many leading public men.”

High Times and Low

By 1860, nearly every newspaper east of the Mississippi had some kind of presence on Newspaper Row and telegraphic messages to its inhabitants came in and went like the tide.

One such message, sent by a correspondent for the New York Daily Tribune, proved especially prescient.

Entitled “The Southern Excitement,” the unsigned piece published on Nov. 15, 1860, announces unreservedly that the “conviction grows stronger here every day that some satisfactory solution of the present excitement in the South will yet be found.”

“Precautions have been taken to prevent any collision between federal and state authorities in South Carolina or to excite jealousies which might provoke difficulty.

“There is a very strong disposition there among the more discreet leaders to postpone any demonstration which might test the issue practically until the close of Mr. Buchanan’s term.”

While the unsigned piece makes note of southern delegates’ plan to gather in Charleston following the election of Abraham Lincoln, it also mentions that there are at least some in Congress who were willing to amend the Constitution to create a “new compromise” over slavery.

“All such palliatives, however, do not reach the seat of the disease. South Carolina desires to secede, and now is committed to make the trial in some form. The question had better be settled decisively, rather than suffer to fester,” it said.

With the actual outbreak of the war, journalists began pouring into Washington, eventually pushing the number of reporters working on the row to just under 300.

Among them was Uriah Hunt Painter of the Philadelphia Inquirer.

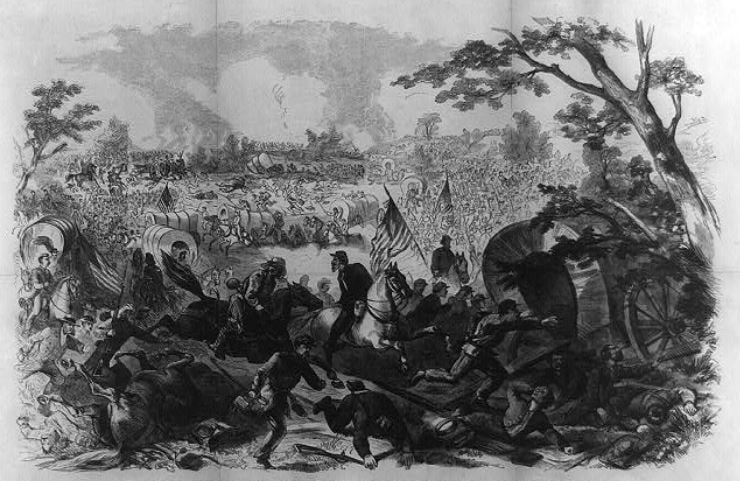

Painter, along with Shaw and Henry Village, another reporter from the New York Herald, were among the eyewitnesses of the first Battle of Bull Run, which took place about 30 miles west-southwest of Washington.

Surprised but undaunted by the fact censorship had been declared in their absence, a move that shut down the telegraph lines out of the city, Painter jumped on a train to Philadelphia, sleeping on the floor of a baggage car.

Working in between bouts of sleep, Painter finished his piece on the Confederacy’s rout of union soldiers just before he arrived at the Inquirer’s offices. As a result, he beat other northern papers by about 24 hours.

Even better, his story was the only one that was right, as the other papers had relied on experts who predicted a northern victory.

There being no Associated Press at the time, everything depended upon a reporter’s individual achievement. Painter’s exploits brought the Inquirer instant credibility as an authority for reliable war news, and the circulation of the paper soon doubled.

The State of the Union

Though wars and elections and other breaking news events often dominated Newspaper Row dispatches, occasionally correspondents were given the luxury of explaining the Washington scene to their fellow Americans.

One such case involved George Grantham Bain, of the Atlanta Constitution. In early December 1893, it fell to Bain to write on President Benjamin Harrison’s delivery of the annual State of the Union message to Congress.

“Each year when Congress comes together, the Senate and House go through the form of appointing a committee to notify the president that Congress is in session and ready to transact business.

“The president knows this quite as well as they — personally; but officially he does not know it until the two senators and three members of the House appear in his office and smilingly advise him of the fact,” Bain continued.

Before this would happen, two carriages would be summoned by the Capitol sergeant-at-arms, and he would accompany the committee to the White House.

When the committee returned, the chairmen of the respective chambers notified them the president would communicate with Congress in writing, in a short time.

“Congress knows this quite as well as the president knows about Congress,” Bain wrote. “It is a constitutional duty of the president ‘from time to time to give to the Congress information of the state of the union and recommend to their consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.’”

The next day, Maj. Octavius Pruden, assistant private secretary of the White House, was expected to board a White House carriage to make his way to the Capitol and deliver the president’s State of the Union address, which he carried in “a big official envelope” to the Senate chamber.

Bain notes that Pruden made the journey up Pennsylvania Avenue “not in the president’s fancy horse and carriage, with its team of horses and jingling English harness, but in a little one-horse affair which is used for executive business.”

“Everyone in Washington knows Mr. Pruden and knows when the little carriage is seen … on its way to the Capitol just after Congress has met, that the assistant private secretary is the bearer of the president’s annual message.”

As for the handling of the State of the Union on Newspaper Row, Bain observed that Harrison followed the example of his immediate predecessors and took steps to ensure that his full message would be published by newspapers across the country the next day.

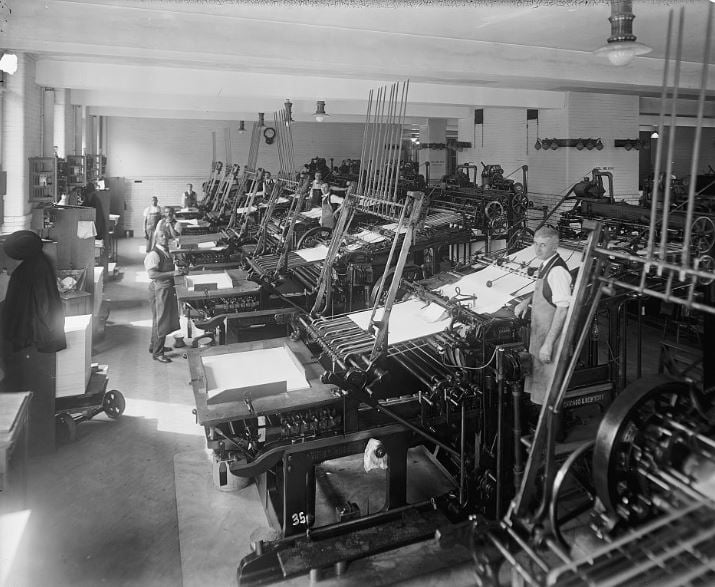

First, Harrison had his State of the Union put into type at the Government Printing Office and had copies taken to New York by White House messenger 24 hours before the message was to be delivered to Congress.

In New York the messenger met with representatives of the various press associations and the manager of Western Union.

By prior arrangement, Western Union would carry the State of the Union free over its wires to every city where there was a newspaper receiving telegraphic dispatches.

Because of its size, the message would be sent out between the hours when the press associations had sent a “good night” notification to their member papers and dawn the following morning.

Meanwhile the papers on the receiving end of the lengthy message were made to promise that they would not print the State of the Union until it was delivered to Congress later that afternoon.

“The signal for the release of the message is given usually from the galley of the Senate,” Bain wrote.

“As soon as the secretary of the Senate reads the first word of the message, the signal is given to the telegraph operators in the corridors, and they send dispatches over the country telling the newspaper publishers that they may ‘release the president’s message.’ Usually, these papers have the message in type and the presses ready, and two minutes after the release is received, they are grinding out extra.

“The reason for all this, of course, is that the State of the Union was too long not to get started in advance. And if there was a storm or the wires were working badly, the message might not get to the country all day,” he added.

Shenanigans and Scoops

Despite these efforts, there were also enterprising reporters on Newspaper Row who tried to get a scoop for their papers and get all or part of the State of the Union to them early.

Because the message had to be set into type and printed at the GPO, there was always a possibility that someone might steal it.

“That danger has been reduced to a minimum, but some danger still exists,” Bain wrote.

In fact, many on Newspaper Row believed the SOTU delivered to Congress by President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1881 had been stolen by an employee of the branch printing office in the Treasury Department.

The whole point of using the Branch Printing Office had been its greater security, yet somehow a copy of the State of the Union had gotten into the hands of a Newspaper Row correspondent who offered it for sale to three newspapers a day before it was delivered.

The papers, located in New York, Cincinnati and Chicago each agreed to pay $500 for it, but the reporter never got his money from the latter.

Bain said what happened was another Chicago paper “got an inkling” of what was going on and told its New York correspondent to look out for an early edition of the New York paper to which the State of the Union had been sold.

“The city edition of the Chicago paper was held back. The difference of an hour’s time between New York and Chicago favored the plan,” Bain wrote.

Once the New York correspondent had the preview in hand, he hastily cut the most important features of the speech out and telegraphed them over a dozen wires to Chicago.

As a result, the Chicago paper printed the chief features of the message at the same time that its rival — who had promised to cough up $500 for the information — printed the message in full.

Bain wrote that the Chicago paper that had been part of the illicit deal then refused to pay up, arguing the simultaneous publication in one of its competitors released it from its obligation.

Amazingly, the reporter who had gotten hold of the speech in the first place then sued the Chicago paper for breach of contract, only to lose when his attorneys allowed the case to go into default.

There is, however, a coda to the story: A correspondent for yet another Chicago paper found out what was happening and, in despair, walked the block over to White House and pleaded his case to Hayes himself.

“He told the president that the other Chicago papers would have it and he did not want to be scooped,” Bain wrote. “The president, very obligingly, went over the chief features of his message and saved the correspondent’s reputation with his paper.”

This was far from the only time an attempt was made to steal the State of Union for the sake of publication in the newspapers.

One year the White House hit upon a plan of cutting the speech up into several “takes” of a few lines each and having them set by different printers so no one could be quite sure what they were setting.

The finished product would then be assembled by one man, who would put the type bearing forms in a vault and lock it. This one man was the only person with a combination to the vault.

“As it happened, there was a young man who had graduated from the Government Printing Office into newspaper work who had some rather crude ideas about enterprise in journalism,” Bain wrote. “He is credited some years ago of attempting to get the bearer of the combination drunk and steal a copy of the message.”

Still another story had it that a Newspaper Row correspondent wore white pants during a visit to the printing office ahead of the SOTU and when the foreman was not looking, sat down on a form of type “of which he was very anxious to obtain a proof.”

“This is one of the stock stories of Newspaper Row,” Bain said.

He then went on to note there are other, less devious ways to obtain information about a president’s annual message to Congress.

He recalled that about a year before the previous presidential election, there was a great deal of curiosity about Harrison’s attitude toward a particular piece of pending legislation.

As a result, Bain said, “his message to Congress was anxiously awaited.”

Two days before, Bain called on a member of the cabinet on some unrelated business and during their conversation, learned the president had read his message to a cabinet meeting and had made some modifications at the suggestion of its members.

“In the most casual way I asked him what the president would say on the subject of [the bill everyone was wondering about], and, to my surprise, he gave me what proved to be a very good outline of that feature of the president’s message,” Bain said.

News Flash From a Railroad Station

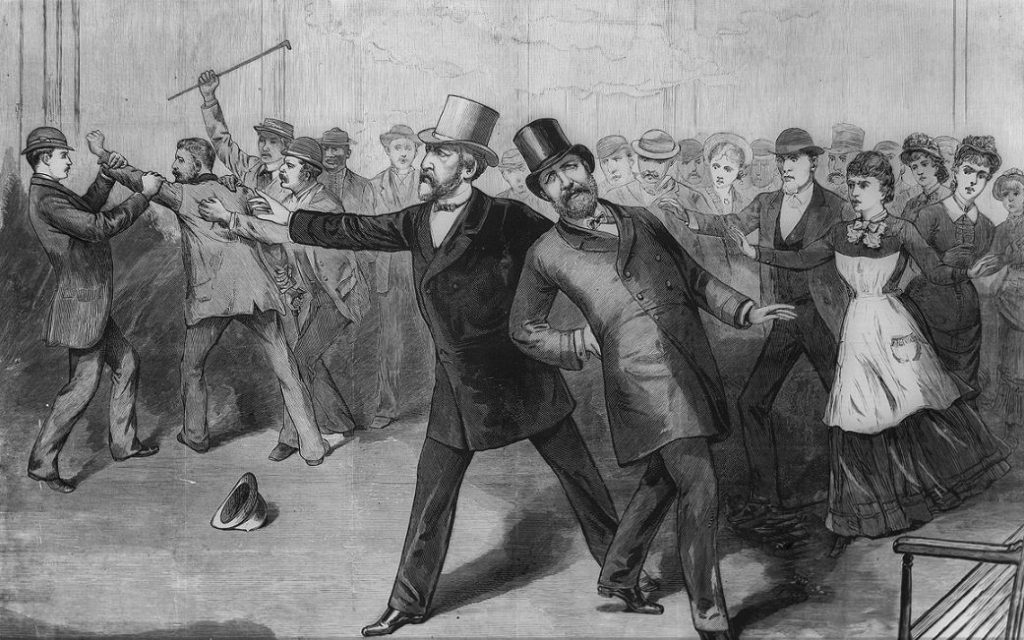

Perhaps no single Washington event galvanized Newspaper Row more than the assassination of President James Garfield at the Sixth Street Station of the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad.

The date was July 2, 1881, and Garfield was headed to his summer home on the Jersey Shore to escape the broiling heat of the district when he was shot by an embittered attorney named Charles Guiteau, who had been rejected for a consular post.

At the time, Garfield and many others in Washington, made little of the threat of assassination. Though Abraham Lincoln’s assassination was still a fresh memory, most saw Lincoln’s murder as an aberration tied directly to the Civil War.

As a result, Garfield had next to no security with him as he walked through the public train station.

He lay mortally wounded in the White House for weeks, undergoing a series of quack medical treatments, before being taken to the New Jersey shore in early September. Garfield died there, from an infection and internal hemorrhage, on Sept. 19, 1881.

Robert Bender, then a 38-year-old wire operator for Western Union, would later tell The Washington Post that the day Garfield was shot was “the busiest day we ever had.”

“Our office sent 590,000 words, mostly press copy, to the newspapers all over the country,” Bender remembered in 1914, still on the job at age 72.

“I was later sent over to do special work at the Washington Jail, where Guiteau was confined. For many days, it was my job to tell the world news of the aftermath of Garfield’s assassination.”

The Detroit Free Press reported on what it was like to be on the receiving end of these terrible dispatches from Newspaper Row.

The early dispatches, it said, had been just a bare statement of fact, without particulars.

“Yet they had a remarkable effect on the people. By 11 o’clock, the bulletin boards of the Free Press and other newspaper offices and that of the Western Union Telegraph Company’s offices were scenes of extraordinary excitement,” the newspaper said.

“Hundreds of men gathered around them, all trying to get near enough to read the awful intelligence and each eagerly asking his neighbor what he had heard or learned,” it continued.

The unidentified writer of the piece noted that the sidewalk around City Hall, not far from the Free Press building, “was crowded with excited knots of men” and the roadway filled “with an almost unbroken line of carriages” from which “occupants hailed every acquaintance they met with inquiries as to the all-absorbing event.”

“Grief and indignation took full possession of them and for the time being noticeably checked all kinds of business both public and private,” the newspaper said. “The air seemed laden with the gloom of the great tragedy that touched the nation’s heart in its tenderest spot.”

Gas Lights and Election Returns

It was perhaps inevitable that election news would be both a centerpiece of Newspaper Row reporting and one of its greatest draws.

For much of the street’s early life as the epicenter of the Washington news media, the outcome of state elections, and whether Republicans or Democrats prevailed, were interpreted as a sign of whether America was closer to coming to blows over slavery.

Later, the same results were looked at as portents of the future of reconstruction and the nation as a whole.

This was especially true on an October night in 1876, as what would come to be remembered as one of the United States’ most controversial presidential elections, appeared to draw to a conclusion.

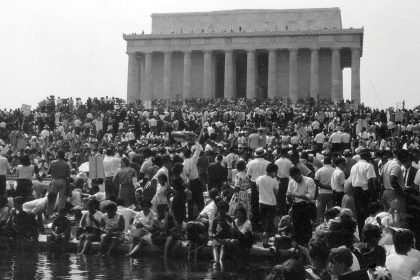

As the fall’s early darkness blanketed Washington, large, excited crowds began gathering in front of the telegraph and newspaper offices on Pennsylvania Avenue and Newspaper Row anxiously inquiring about the latest news, the Boston Daily Globe reported.

By midnight or early morning, they expected to know whether Republican Rutherford B. Hayes or Democrat Samuel Tilden had been elected president.

The greatest crowd was gathered in front of the Atlantic and Pacific telegraph office, which had opened around the corner from Newspaper Row in the late 1860s, just a few steps from the Willard Hotel.

A second large crowd assembled outside the Western Union office, and both companies were publishing dispatches, posting each new piece of news as it came in on their large outdoor bulletin board.

“Each new dispatch would be read by those nearest the board, then told to those in the outer circles and then all hands would fall to commenting, speculating and prophesying until the next dispatch appeared,” the Boston Globe’s correspondent reported.

Each report of a Republican majority or Republican win was heralded with a buzz of approval and occasional cheers. Reports of Democratic gain were met with silence at first, “then, occasionally, a Democrat will break in with a sneering remark and a heated discussion will ensue.”

In the meantime, a number of correspondents on the row were receiving private dispatches from their home offices, causing their offices to fill to overflowing with partisans for one side or the other.

In the end, even as large crowds stayed into the wee, small hours, no clear winner emerged because the outcomes in three states: Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina were far from clear.

Both Hayes and Tilden claimed victory in all three states, but Republican-controlled “returning” boards, bodies designated by law to canvass election returns, would determine the official electoral votes.

Days after the huge gatherings on Newspaper Row, the returning boards in all three states argued that fraud, intimidation and violence in certain districts invalidated votes, and they threw out enough Democratic votes for Hayes to win.

While all this was going on, a kerfuffle arose in Oregon. Hayes won the state, but one of the Republican electors, John Watts, was also postmaster, and the U.S. Constitution forbids federal officeholders from being electors.

Watts planned to resign from his position to be a Republican elector, but the governor of Oregon, who was a Democrat, disqualified Watts and instead certified a Tilden elector.

The Constitution stipulates that the electoral votes be directed to the president of the Senate, who was Republican Thomas W. Ferry. Although Republicans argued that he had the right to decide which votes to count, Democrats disagreed and argued that the Democratic majority in Congress should decide.

A compromise was reached, and on Jan. 29, 1877, the Electoral Commission Act established a commission of five senators (three Republicans, two Democrats), five representatives (three Democrats, two Republicans), and five Supreme Court justices (two Republicans, two Democrats and one independent) to decide which votes to count and resolve the dispute.

Though Hayes did not initially support the commission, it eventually voted eight to seven to award him the electoral votes from South Carolina, Florida and Louisiana, and one from Oregon.

Democrats in the House balked and threatened to delay the resolution of the election with frequent adjournments and filibusters.

Finally, an informal backroom deal was struck, the so-called Compromise of 1877.

In return for conceding the 20 contested electoral votes to Hayes, the Democrats got Republicans to agree to withdraw federal troops from the South, marking the end of Reconstruction.

The Closing of the Willard

By the summer of 1871, Newspaper Row had weathered a Civil War, a presidential assassination and an impeachment, but it was a dispute between hotelier brothers Henry and Joseph Willard that really threw reporters and editors for a loop.

From the very start of the row’s existence, the Willard Hotel has been a glittering neighbor that brought a kind of jostling, heady fizz to the neighborhood, especially during congressional sessions.

Now, abruptly, the gaslights had been extinguished, and, as one Newspaper Row reporter put it, “the footfall of the occasional passer-by” was left to reverberate like “the echo of a mourner’s sob in a damp sepulcher.”

The closure, which lasted for years, had a depressing effect on the entire row. Reporters who spent days and mostly nights on the street, talked endlessly about how they missed the brilliant light that once streamed well into the morning from the hundreds of hotel windows.

Even worse, many said, was the absence of the womanly forms that had routinely flitted across hotel room curtains or “tripped in and out of the Willard’s ladies’ entrance.”

“And it was a rich place for news too,” one newspaper correspondent said. “All of it is no more. And all we’re left with are lofty somber walls.”

“We shall rejoice heartily if the brothers Willard, to whom the property belongs, settle their little difference and allow this great hotel to once more be thrown open to the public,” another correspondent said.

The sad truth was the closure of the Willard was symbolic of other changes that were occurring on the row.

A Scandal Divides Lawmakers and the Press

From its earliest days Newspaper Row was marked — some would say defined — by the cozy relationship that existed between Republican lawmakers and the newspapers and correspondents setting up shop in Washington, D.C.

In the end, what ended that relationship and set the stage for today’s far more adversarial press, was the same impulse that led James Gordon Bennett to lean so heavily into his coverage of Helen Jewett’s murder — the desire to feed the public’s love of a good scandal.

The story began as the Civil War was winding down and the Union Pacific Railroad began laying the groundwork for construction of the eastern portion of the first transcontinental railroad.

The project, and the business model that would support it, were the brainchild of Union Pacific executive Thomas Durant, the basic idea being to reap huge profits from railroad construction while guaranteeing that he and other investors were exposed to little if any risk.

The first step in the plan entailed purchasing an idle fiscal agency, Crédit Mobilier of America, and effectively turning it into the intermediary for the construction project. Durant then paid a friend, Herbert Hoxie, to submit a construction bid for the project. As it happened, it was the only bid on the work, and when it was unanimously approved by the railroad, Hoxie’s contract was signed over to Crédit Mobilier.

While all of this was opaque, up to this point no laws were broken.

Meanwhile, Durant was paying Crédit Mobilier with money given to the Union Pacific by government bonds and risk-taking investors, and he began subcontracting the actual railroad work to real construction crews while using inflated estimates to ensure significant profit.

Estimates handed down over the decades suggest the true cost of the line was about $50 million, while Crédit Mobilier billed about $94 million.

Union Pacific executives pocketed most of the $44 million difference, though they did use some of it — and roughly $9 million in discounted stock — to bribe several Washington lawmakers for funding, laws and regulatory decisions favorable to the investors.

Everything, it seemed, was going Durant’s way. But a conflict in the Crédit Mobilier boardroom brought construction to a standstill.

Concerned that only 12 miles of track had been laid, President Abraham Lincoln asked Republican Rep. Oakes Ames, of Massachusetts, a member of the House Committee on Railroads, to intervene.

As it happened, the Ames family was in the construction business, and the representative’s brother, Oliver, was actually a Crédit Mobilier investor.

But Oakes Ames effectively achieved everything Lincoln wanted. The boardroom battle was resolved and construction resumed. The problem, he would later claim, was that he was soon overwhelmed by legislators demanding a piece of the action.

By 1867, he had distributed stock at a substantial discount to two senators and nine representatives.

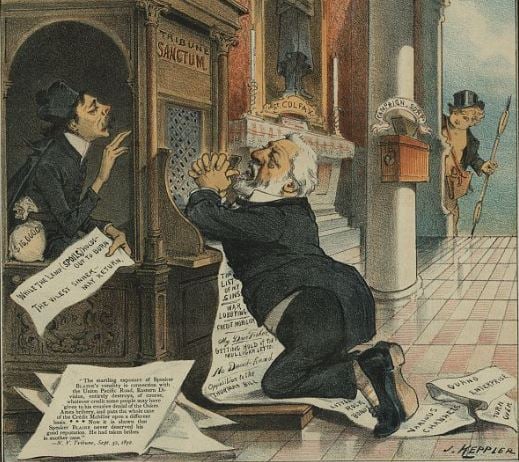

The secret dealings erupted into a full-blown scandal on Sept. 4, 1872, when a correspondent from the New York Sun broke the story of the overbilling.

At the time, President Ulysses S. Grant was running for his second term, and the anti-Grant faction in the press had a field day with the soon mounting revelations, calling the scheme “the most damaging exhibition of official and private villainy and corruption ever laid bare to the gaze of the world.”

Though the scandal appeared to have no effect on the election, House Speaker James Blaine, who was initially — and wrongly — identified as a stock recipient, moved that Congress investigate the charges.

Dragged before an investigative committee, Ames insisted that nothing illegal had transpired, and agreed to talk, at length, about what had happened. Several of his colleagues pushed back at his subsequent revelations, and Ames responded by producing a ledger book detailing every transaction.

The ledger definitively cleared the House speaker, but incriminated Vice President Schuyler Colfax and 13 members of Congress.

On Newspaper Row, many members of the correspondent fraternity were almost giddy, and their publishers were over the moon due to the response of the public, which couldn’t seem to get enough of the case.

As often happens in such cases, the end of the committee investigation was an anticlimax. Rather than take action against everyone involved, it chose only to punish Ames himself and James Brooks — the sole Democrat implicated — with congressional censure.

“Whitewash!” a number of Newspaper Row correspondents declared.

Ironically, Brooks had been among the very first Washington correspondents, having arrived in Washington in 1832 as a writer for the Portland Advertiser. Now a scandal exposed by the press had ruined his career.

But the repercussions for the press and Congress went far further. The extensive coverage Newspaper Row had devoted to the Crédit Mobilier scandal chilled the correspondents’ close relations with congressional leaders.

“Up to that time Newspaper Row was daily and nightly visited by the ablest and most prominent men in public affairs,” wrote Henry Boynton in the Cincinnati Gazette.

“Suddenly, with the Crédit Mobilier outbreak, and others of its kind that followed it, these pleasant relations began to dissolve under the sharp and deserved criticism of the correspondents.”

Years of estrangement followed, as newspapers continued to use the Crédit Mobilier incident as a vehicle for sowing widespread public distrust of Republicans, Congress and the federal government in general.

According to Boynton, “each assumed relations bordering upon a warlike attitude towards the other.”

And the animus consumed both political parties, sometimes to the row’s profound exasperation.

“Newspaper Row is in an unusual quandary tonight over the proceedings of the Democratic conferences today,” wrote the correspondent for the Detroit Free Press on May 3, 1879.

“The Democratic senators and representatives having been so shamefully misrepresented by the Republican newspapers, are disposed to keep remarkably mum when questioned regarding what is said and done during their consultations,” he continued.

“The result is that tonight there is a large number of newspaper men who are left in the dark and have to report a representation of the baseless rumors and speculations to serve as padding in their dispatches,” the aggrieved reporter said.

A Freed Slave Becomes Beloved Personality

While histories of the row tend to focus on the reporters, editors and politicians, there are others, now almost completely forgotten, who were well known and memorable local characters in their day.

Among these was Tom Carter, a freed slave who arrived in Washington from Fredericksburg, Virginia, in 1865.

Carter initially secured work as a porter in a retail store, but as soon as he could, he bought himself a horse and a modest buggy and set himself up in the livery business.

“For almost half a century he sat on the box of a hack, waiting patiently for the fares that came at midnight or maybe nearer dawn,” from W. Gardner Jones Jr. in an obituary of Carter published on Dec. 27, 1924, in the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper.

“He stationed himself around the newspaper offices and the National Press Club, as men seemed to stay up later there,” Jones wrote.

“Sometimes the [W]hite fellows were generous with their tips, and other times, they could not pay him at all. But Tom never kept books on those who owed him. As he grew older, he came to refer to the newspaper men as ‘my boys’ or ‘my [W]hite gentleman friends.’”

They, in turn, called him “Tom” and “probably very few knew his last name,” Jones observed.

By the start of the 20th century, Carter knew his time as livery driver was growing short. He’d already had more than one horse grow old and feeble, and increasingly, motorized cars were coming on the scene.

In desperation, he turned to the National Press Club, which had been founded in 1908, and asked for a job.

Recalling the conversation later, Carter said he spoke with Graham Nichol of the Washington Times, a founder of the club, and had told the newspaper man he’d be willing to do just about anything, with one proviso.

“It was important that whatever the club could offer, it be at night,” he said. “I can’t see to work in the daytime. … I’ve got to have electric lights.”

Carter got the job he wanted, but after only a few months, his health began to fail rapidly.

Members who gathered in the club room to play dominoes and Bridge, passed a hat for Carter twice a week to supplement the modest pension the club was giving him.

When he died, Jones wrote, Carter “did not have a state funeral … but many people are grieving over the demise of the old man … and after all, that is everything that counts when the end comes … whether one is a cabman or a king.”

It wasn’t too long afterward that a kind of death came to Newspaper Row as well. A number of papers, having outgrown their accommodations, had moved to new locations in the city. Other papers simply consolidated their operations in the new National Press Building that rose across the street from the Willard.

“Washington’s Newspaper Row to be wiped out of existence,” blared a banner headline in the Boston Daily Globe on Nov. 17, 1907.

“The one- and two-story ‘shacks’ in which ‘the boys’ once wrote their stories of national events at the nation’s capital have given way to business blocks and big hotels.

“In 50 years, the city has undergone a transformation,” the Globe’s correspondent observed. “And the section between Pennsylvania Avenue and F Street on 14th has responded to the demands of trade.

“With the removal of the offices of the Omaha Bee, Troy Times, Deseret News and the Buffalo Times to other localities, Newspaper Row, as it has been known for half a century in Washington, ceases to exist, the encroachment of business enterprises compelling the representatives of newspapers maintaining bureaus at the Capitol to seek other quarters.”

The anonymous correspondent continued: “The history of Newspaper Row is contemporaneous with the history of the United States for the last half-century. Many famous editors and writers of note in that period had offices on the row or its immediate vicinity. History has been made here.”

To learn more about Washington, D.C.’s historic Newspaper Row, check out these books: “Press Gallery: Congress and the Washington Correspondents,” by Donald A. Ritchie, and published by the Harvard University Press, and “Tales from The National Press Club,” by Gil Klein, published by the History Press. Gil’s book can be found, on sale, here.

Dan can be reached at [email protected] and at https://twitter.com/DanMcCue