Financial Experts Advise Lawmakers on Future for AI

WASHINGTON — Lawmakers sought answers Wednesday on how the U.S. financial industry could reap potentially huge benefits from artificial intelligence while avoiding devastating risks.

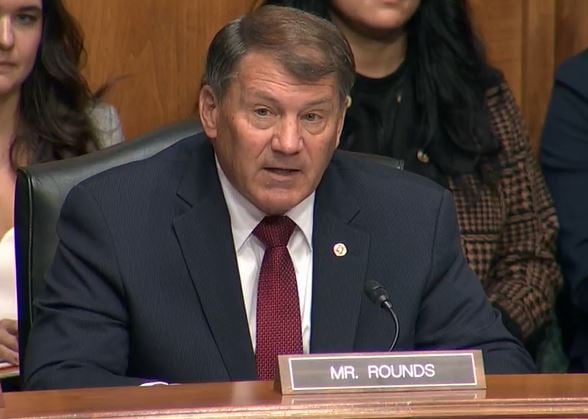

Sen. Mike Rounds, R-S.D., summed up the balancing act Congress wants to perform by asking financial industry experts, “How do we not screw it up?”

“We stand in the middle of a journey of monumental change,” Rounds said during a hearing of the Senate Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee.

Some innovations created through the machine learning of artificial intelligence are not regulated, creating loopholes in the laws that could deeply hurt banks, the stock market and the nation’s economy, according to experts who testified at the hearing.

So far, financial industry executives have discussed hopes for bigger profits with AI but largely ignored how it could help fraudsters build on the $50 billion a year banks estimate they lose to computer-based scams.

AI innovations of recent years have allowed banks to tailor promotions to personalized interests of customers, reduce the manpower needed to comply with regulations, more closely analyze credit risks of borrowers and restock the cash in ATMs.

In recent quarterly reports, the financial institutions — along with other corporations — predicted greater efficiency, lower costs and bigger profits using AI.

Lawmakers at the Senate hearing cautioned against a rush by bankers toward AI-inspired profits that could force them to make remedial repairs if they do not prepare for the risks.

In one example mentioned at the hearing, banks sometimes use voice recognition technology to identify their customers for phone transactions. Recent AI language generators can create voices that mimic other persons, potentially allowing fraudsters to mimic bank customers while stealing their money.

“The Silicon Valley ethos of move fast and break things is dangerous for both our financial system and our entire economy,” said Sen. Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio, chairman of the Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee.

He also asked whether the efficiencies the financial industry seeks from AI would be worthwhile only for its top executives but result in widespread layoffs for lower level employees.

“Efficient for whom?” Brown asked.

Experts who testified at the hearing cautioned against the heavy hand of government regulation that could stifle innovation, perhaps leaving the United States behind China and other international competitors.

“It is an area of fierce international competition,” said Daniel S. Gorfine, chief executive officer of the financial industry advisory firm Gattaca Horizons LLC and a Georgetown University law professor.

So far, the United States has been a leader with AI but will hang on to any lead only if government regulators encourage innovation, he and other experts said.

He recommended that regulators assess emerging AI opportunities but avoid “a singular focus on risk” that “can blind us to the greater benefits that may be present.”

“The fear of future harm, however, should not broadly block development of AI in financial services,” Gorfine said.

Melissa Koide, chief executive officer of FinRegLab, a financial services technology research organization, said improved credit analyses from AI could extend credit to about 50 million U.S. adults whose credit risk cannot be assessed through traditional methods.

The result is “the potential to improve fairness and inclusion” in business opportunities for persons who are overlooked by financial institutions now, she said.

Michael Wellman, a University of Michigan computer science professor, said the early stage development of AI holds unforeseen promises and perils for the financial industry.

“AI has surprised us many times,” Wellman said.

You can reach us at [email protected] and follow us on Facebook and Twitter