Reflecting on the 60th Anniversary of the March on Washington

COMMENTARY

The 60th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom provides an opportunity for us to reflect on the hopes and promises advanced at the March, and the actions and accomplishments that followed.

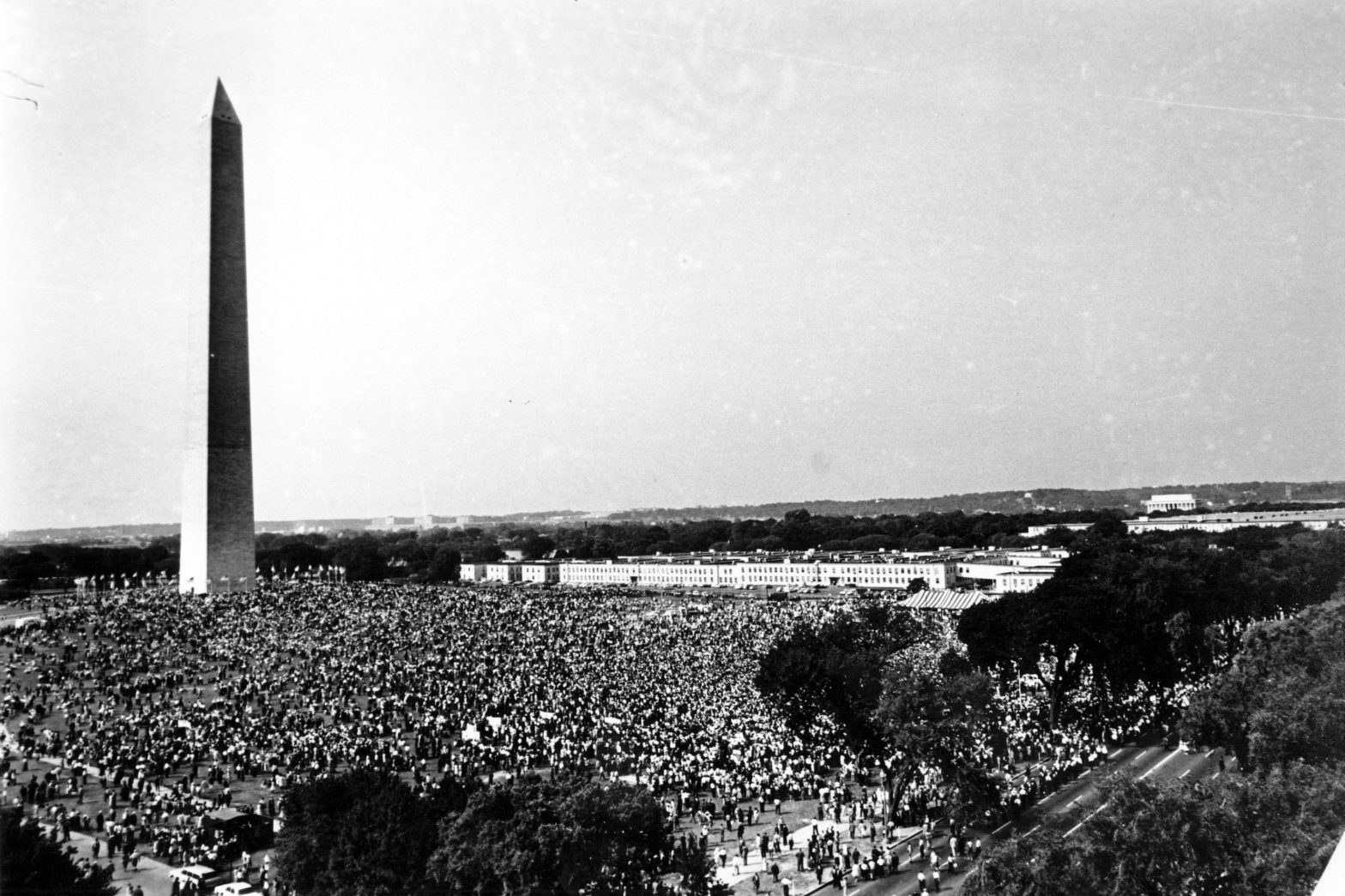

The 250,000 participants in the march represented the nation’s first, and largest, collective cry and demand for jobs, freedom, and social and racial equality. The gathering was a recognition that the time for unmet promises was over, and the time for action long overdue.

Indeed, the presence of these thousands was a declaration of collective protest and a manifesto for social and racial change.

I was in Paris, France, when the march took place, but it was covered in the French press and on French television. The next day some of us, some with tears, met at the American Book Store to discuss the march and its possible impact and ramifications.

We all believed, hopefully, that America was turning over a new social and racial leaf — that a new, more open and honest social and racial narrative would emerge.

I also received letters from siblings and friends who were optimistic that the march might indeed be a turning point in the nation’s social, economic and political history.

On a personal level, the march, and the messages conveyed, ignited a spark of racial consciousness, first because I was a Black man from South Carolina, and I remembered the many racial insults I, and many others, endured growing up in Charleston, South Carolina.

But there was also the heightened national consciousness I felt as an American, and the feeling that at last my country was recognizing its racial past and its flaws, and was now ready and willing to grow up and become an adult, socially and racially.

Later I read fuller accounts of march participants in Jet and Ebony, and there were commitments from participants on specific messages received at the march and what they wished to do upon their return home.

I have seen no data on what the returnees did, but we do know that in 1964, a year after the march, the U.S. Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, and two years later, the Voting Rights Act. The latter outlawed the actions southern states traditionally implemented to prohibit Blacks from voting: literacy tests, poll taxes and White-only primaries, and the grandfather clause.

The abolition of these voting restrictions opened the gates to increased Black voting throughout the South, resulting in large numbers of Blacks elected as mayors and council persons.

One of the most notable examples of this change was the election of Henry Marsh as mayor of Richmond, Virginia, a change that stemmed from the desire of Richmond’s ruling class White elites to annex portions of surrounding Chesterfield County in order to dilute a growing Black Richmond voting population. Though the annexation was permitted to remain, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the city to adopt a district plan. Blacks not only elected five of the nine candidates on the city council, but the council selected Marsh as the city’s first Black mayor. This is notable because at that time mayors were not elected at large.

Despite the advances in job opportunities, education and housing, the reality in contemporary Black America and the nation is continued deficits in these areas.

That is, there is more work to be done.

Blacks continue to face job and promotion discrimination and housing restrictions. Many Blacks in primary and secondary schools attend often-underfunded and largely segregated schools within largely segregated Black communities. These schools are often just as segregated as they were before the Brown decision.

On Saturday, August 28, 1993, my daughter Kimya and I participated in the 30th anniversary of the March on Washington. Although there were only 100,000 participants, the mood was joyful and the speeches pointed to some of the gains Blacks have made in the intervening years, and how the fight and the struggle had to continue to reach the desired goals.

On the return to Richmond, attorney James Sheffield called a few of us together to create an agenda for action. We met several times and proposed many ideas for social change, but were unable to create the programs and organizations that would clearly and cogently address and implement the agenda we desired. I still remember the protest songs and spirituals we sang, often erupting spontaneously, on the way to the march, and on our return to Richmond.

Lastly, there is an issue of a dream deferred. From the 1963 march, the most obvious change for Blacks has been political, with the majority of this change occurring in the South where Blacks have faced the greatest political obstacles.

The greatest challenge for vast numbers of contemporary Blacks, however, is economics and an accompanying problem of health. In fact, the two are intricately linked.

Whereas other racial and ethnic groups have devoted their time and energy towards group solidarity in the fulfillment of economic power, and have created successful urban, ethnic and economic enterprises that have given them a high degree of economic self-sufficiency, Black America has devoted virtually all of its time and energy towards breaking down racial barriers between it and the larger dominant White society.

Other ethnic groups, especially racial groups, have payed little to no attention to participating in politics and voting. They understood that the key to group and individual success in America rests on economic success.

As John Moeser and I noted in our book on the Richmond annexation case, Blacks may have acquired political power in Richmond, may elect a series of mayors, but the real decision-makers continue to be the business class, which resides on Main Street. The courts may mandate political changes, but they cannot mandate a group’s economic holdings and power. And as we have seen across the country, Black political power is seldom translated and transferred into Black economic power.

Thus, the next stage of the struggle must be an economic struggle, begun and sustained by Blacks to organize themselves, as other ethnic-racial groups have done, to gain a degree of group economic self-sufficiency within the American ethnic mosaic.

Both marches, in 1963 and 1993, were important symbols for both Black America and all Americans, for the ideals they proclaimed — freedom, democracy, equality and justice — must be consistently and persistently held high, even if we as a nation are unwilling and unable to live up to the ideals accompanying these vaunted goals, as scholars such as Du Bois and Myrdal have reminded us. Those historians and sociologists among us understand the dynamics of social movements and social change.

The spark lit 40, 50 or 60 years ago may be smoldering somewhere, unknown to any of us.

But somewhere, and someday, that spark may ignite into a major firestorm. That is the message I give to my students who often express great disappointments over inequalities and injustices in American life. I tell them the fight and struggle for freedom, justice and equality must be constant. I always advise them to become “long-distance runners” in that fight.

Lastly, I often recite the words of the Black spiritual: “Walk together children, don’t you get weary.”

Rutledge M. Dennis is a native of Charleston, South Carolina. He received his degrees in sociology from South Carolina State University (B.A.) and Washington State University (M.A. and Ph.D). He was the first coordinator of the African American Studies Program at Virginia Commonwealth University and is currently a professor of sociology in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at George Mason University, where he specializes in the sociology of ideas, sociological theory, race and ethnicity, and studies in W.E.B. Du Bois.