Exercise, Mindfulness Training Found Not to Boost Cognitive Performance in Older Adults

ST. LOUIS — Exercise and mindfulness training under the supervision of coaches may have a wealth of benefits, but according to a new study, boosting cognitive performance isn’t one of them.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, and the University of California, San Diego, studied the cognitive effects of exercise, mindfulness training or both for up to 18 months in older adults who reported age-related changes in memory but had not been diagnosed with any form of dementia.

The findings were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

According to the researchers, all 585 participants in their study, people aged 65 to 84, said they worried about memory problems and other age-related cognitive declines.

They were divided into groups that did exercise, mindfulness, both or neither.

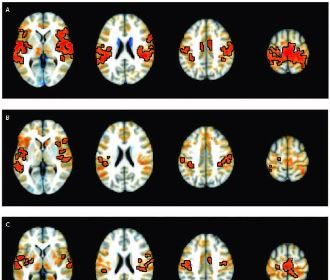

After 18 months, the researchers tested their memory and did brain scans, but found no significant difference among the groups in terms of cognitive improvement or increased brain volume.

The researchers said there are several potential causes for their findings.

First, all groups showed increases in cognitive performance over time, so it could be posited that all interventions (including health education) benefited participants equally and these increases reflect those benefits, and thus the study failed due to lack of a proper negative control.

Arguing against this idea is that the health education intervention was designed for this study so that it would not specifically target cognition.

Further, if cognitive performance increases represented true benefits, one would expect to see a reflection of those benefits in brain structures, yet both structures showed longitudinal declines with all conditions, consistent with age-related atrophy not attenuated by the interventions. In addition, the combination of MBSR and exercise showed no greater change than each intervention alone.

Thus, the increases in cognitive performance likely reflect expectancy or practice effects from repeated exposure to the assessments.

Another potential cause of the findings was failure in target engagement, which could result from poor participant adherence, low intervention fidelity by instructors, low intensity of interventions or low reliability of outcome measures.

Yet another possibility accounting for lack of detectable effect of interventions is that participants were generally healthy and potentially insufficiently sedentary at baseline, thereby limiting potential for benefiting from lifestyle interventions.

The researchers are continuing the study to see if the results will change given additional time.

Dan can be reached at [email protected] and at https://twitter.com/DanMcCue