Emancipation Proclamation Written in War Department’s Telegraph Room

WASHINGTON — It was the big news of the most recent Juneteenth celebration.

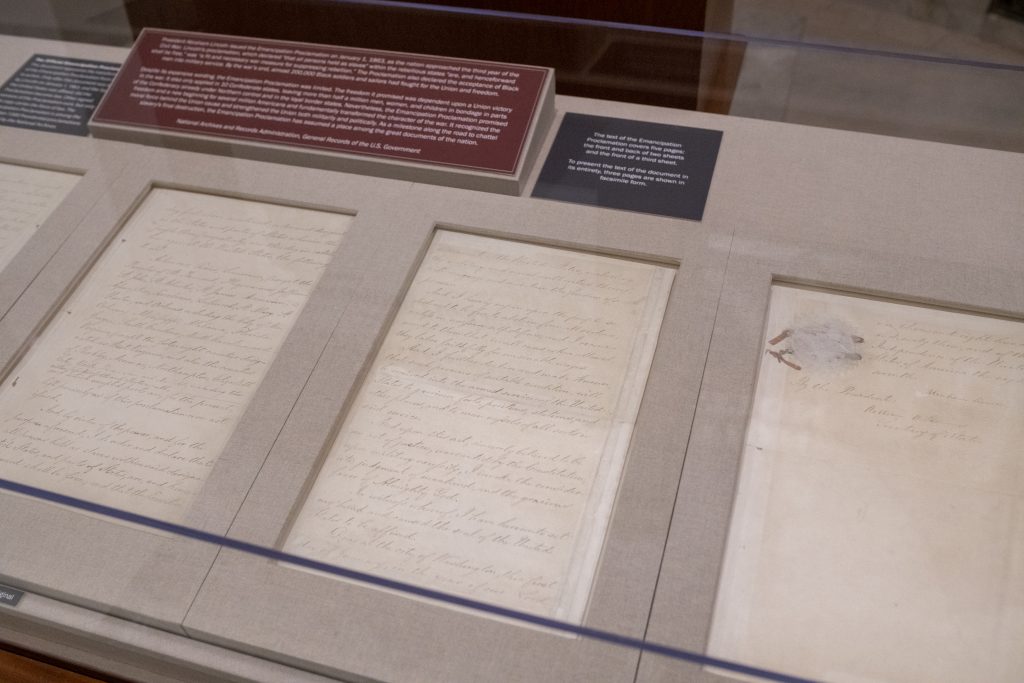

After annually placing the document on temporary display the past two years, the National Archives announced the Emancipation Proclamation would soon have a permanent home in its building’s rotunda, alongside the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution of the United States and the Bill of Rights.

Though assessments continue to determine the best display environment for the hallowed text — the vital prerequisite before its permanent display comes to pass — the current plan calls for showing one side of the proclamation, a double-sided five-page document, alongside facsimiles of the reverse pages.

The original pages on display will be rotated on a regular basis to limit light exposure.

“Once a timeframe has been selected [for debuting the permanent display], this information will be released to the public,” a spokesperson said in an email to The Well News.

All of this planning begged a simple question — how much do folks actually know about the proclamation and how it was written?

And once we began delving into that question for our own edification, we bumped up against another, odder line of inquiry — what was with the spiders and what role did they play in President Abraham Lincoln’s drafting of the historic document?

As nearly every child learns before they leave elementary school, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863, as the nation approached the third year of what had proven to be an unrelentingly bloody Civil War.

By that New Year’s morning, combatants and noncombatants alike were dying by the hundreds every day, and the president hoped the proclamation would effectively put a badly needed thumb on the scale in the Union’s favor, hastening an end to the bloodshed.

Specifically, he hoped to inspire all Black people — enslaved people in the Confederacy in particular — to rally to the Union cause.

That’s why the proclamation declared “that all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.”

It also decreed that freed slaves could be enlisted in the Union Army, thereby increasing the Union’s available manpower.

In addition to its impact domestically, Lincoln also believed the move would further stigmatize the Old South, keeping England and France from giving it formal recognition as a new country and the military aid that would come with it.

What the carefully crafted statement did not do, however, was actually “free the slaves,” as is so often said.

As a military measure, the proclamation was actually fairly limited.

The proclamation freed only those slaves being held in states that had seceded from the Union — state’s Lincoln couldn’t control on a northern victory or southern capitulation.

Further, it left slavery untouched in the so-called border states that had remained loyal to the union, and it exempted parts of the Confederacy that had already come under union control.

Still, like so many other documents written by Lincoln’s own hand, it was a masterstroke, forever altering the stakes in the war between the states and bringing the United States ever closer to reflecting the ideals captured in the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights.

In short, the fight to “preserve the union” was from then on a war to secure the rights of men, women and their children.

Given the loftiness of his goals, one could well imagine Lincoln sitting straight-backed behind his large wooden desk, gravely writing with stern deliberation to get each nuance of the proclamation just right.

Here too, one would be slightly off the mark.

From the moment the South bombarded Fort Sumter in South Carolina in April 1861, Lincoln was a man obsessed with the latest news from the front.

To get it, and to relay his orders to his generals, he had a telegraph room established in the War Department, mere steps from the Oval Office.

Located where the Old Executive Office Building now stands, the so-called War, State and Navy Building was an unremarkable-looking edifice, directly adjacent to the White House stables, but it quickly became Lincoln’s stomping ground.

David Bates, a telegraph operator hired just two weeks after Sumter fell, would later recall seeing Lincoln “almost daily.”

“It was his custom to visit the telegraph office morning, afternoon and evening to receive the latest news from the front,” Bates told The Washington Post in 1905.

“He made the telegraph office a rendezvous, usually sitting at the desk of Maj. Eckert, for whom he had a very high regard,” he said.

The major Bates referred to was Thomas Eckert, chief of the War Department telegraph staff throughout the conflict. Lincoln had intervened when Secretary of War Edwin Stanton wanted to dismiss Eckert from the post, and Eckert, according to those who worked under him in the telegraph room, “couldn’t do enough to show his gratitude.”

The incident warrants a little elaboration because it explains how the telegraph office wound up in the War Department in the first place.

Much has been made of Lincoln’s cabinet being a “team of rivals,” and those rivalries extended to the cabinet and the president’s generals as well. Early on in the hostilities with the South, Stanton was annoyed that telegrams went first to Gen. George McClellan, and only then to his desk.

In response, Stanton accused Eckert of neglecting his duties, and during the ensuing confrontation in the secretary’s office, Eckert tendered his resignation. It was then that Eckert suddenly felt a hand on his shoulder, and turned, to his surprise, to find Lincoln standing beside him.

“Mr. Secretary, I think you must be mistaken about this young man neglecting his duties, for I have been a daily caller at Gen. McClellan’s headquarter for the last three or four months, and I have always found Eckert at his post,” the president said.

Lincoln went on to note that despite his frequent visits to get the latest news from the army, he never saw any reporters or outsiders in the office.

Stanton tore up Eckert’s resignation, apologized for the misunderstanding and promoted him to major on the spot. The next day, much to McClellan’s consternation, all of the administration’s telegraph operations were centralized at the War Department.

Lincoln Befriends the Young Telegraph Operators

With that, Lincoln became an almost constant presence in the lives of the telegraph operators.

“During some of Mr. Lincoln’s daily visits to the War Department there were many spare moments when he waited for fresh news from the front or for the translation of long cypher messages,” Bates recalled.

“He would fill up this time frequently by telling stories or reading aloud from some humorous article from a newspaper,” he said.

Lincoln was especially fond of the work of David Ross Locke, a journalist turned humorist and political commentator, who published under the pseudonym “Petroleum V. Nasby.”

Locke’s “Nasby Letters” sought to rally support for the Union cause by lampooning the Confederacy-supporting title character as bigoted, dim-witted, work-resistant and often drunk or close to it.

Bates said Lincoln would often stop his reading to laugh out loud at the foolish things “Nasby” said, especially when they were directed against the president or his administration.

“One of Nasby’s catch phrases which Mr. Lincoln especially enjoyed repeating was ‘oil’s well that ends well,'” Bates said.

“To those of us who watched him day-by-day it was clear that the telling of funny stories and the reading of these articles was really the safety value that furnished him sorely needed relaxation,” Bates said.

“Often, indeed, he would lean back in his chair with his feet on the desk in front of his long body and relapse into a serious, thoughtful mood, idly gazing upon the traffic on Pennsylvania Avenue,” he said.

It was from a similar vantage point that Lincoln watched his close friend, Col. Edward Baker, march off with his troops to confront Confederate soldiers at Ball’s Bluff, near Leesburg, Virginia.

Baker, who had traveled with Lincoln to Washington from Illinois, was shot six times over several hours of fighting, and finally killed after being shot in the head at close range. Lincoln was deeply affected by Baker’s death, and later named his second son, Edward Baker Lincoln, in his friend’s honor.

Bates recalled that whenever Lincoln lapsed into one of these thoughtful moments, “The inherent sadness of his features was a study even to us youngsters.”

“He would not remain idly pensive for long,” the former telegraph wire operator remembers. “Out of the cloud he would come, his expressive face would light up, and he would make some funny remark.”

Another wire operator, Albert Chandler, recalled how each time Lincoln returned to the telegraph room he’d head directly to the drawer where the latest dispatches were kept.

“On each occasion, he would open the drawer, and, beginning with the last dispatch, would read over the copies until he reached the one he had previously read. Then he would generally remark: ‘I’m down to raisins,'” a term Chandler and other telegraph operators said they initially found hard to fathom.

“He explained this remark by telling the story of a little girl who ate too much at her birthday party and got so sick that she lost it,” Chandler said.

“The story ended with the doctor remarking that the girl was out of danger because she was ‘down to raisins,'” he said.

Lincoln’s constant presence in the telegraph room and his closeness with the young telegraph operators that toiled there could, on occasion, be a problem for Stanton and the War Department.

The president, it turns out, was something of a leaker, “freely telling callers the contents of dispatches from the armies,” Bates recalled.

“There were many occasions when he disclosed to the public in advance Army maneuvers of special importance and which leaked through to the enemy, with the result of defeating our plans,” he said.

In response, Stanton told the telegraph operators to keep the more sensitive messages out of the incoming drawer and to bring them directly to him.

Stanton especially wanted to slow Lincoln’s reading of anything to do with important army movements or the progress of battles.

“Mr. Lincoln’s keen eyes soon discovered something wrong, and without criticizing our course would occasionally ask, with his eyes twinkling, whether the secretary did not have some later news,” Bates said.

“We could not deceive him, and he would then go to the adjoining room, and address Mr. Stanton as ‘Mars,’ [and] would ask if he had any later news from the front.”

Chandler remembered an afternoon when the president was looking in the drawer for new dispatches, when he suddenly heard a newsboy selling his wares outside on Pennsylvania Avenue.

“Did I ever tell you the joke the Chicago newsboys had on me?” Lincoln asked.

“Just before my nomination I was in Chicago attending a lawsuit. A photographer asked me to sit for a picture and I did so,” the president said. “Well, this coarse, rough hair of mine was in a particularly bad tousle and the picture represented me in all its fright.

“After my nomination, this being about the only picture of me there was, copies were struck off to show how I looked,” he continued. “Well, the newsboys carried them about to sell and as they did so, they cried: ‘Here’s your old Abe; he’ll look better when he gets his hair combed.'”

Chandler said, “He laughed over this as heartily as though it had been a good joke on someone else.”

New York Herald Captures the Writing of the Proclamation

By February 1926, when the New York Herald writer Charles White sought to put together a piece commemorating Lincoln’s birthday, Bates was the last surviving member of the telegraph room team.

And it was Bates who would recall witnessing Lincoln’s writing the Emancipation Proclamation, little by little, during the late summer of 1862.

By this time, the president had floated the idea of the proclamation past his cabinet, only to have it largely oppose the idea as too radical.

Disappointed, but undeterred, Lincoln resolved to put his thoughts down on paper. The only problem was his office was a fairly public space, with cabinet members and others constantly streaming in to see him.

As an alternative, the telegraph room was a perfect choice.

Not only did he have privacy there, but it had come to be one of the few places within the White House compound that he seemed to feel entirely at ease.

Lincoln, Bates said, could be secretive when he wanted to be.

“He took people into his confidence only to the extent to which their cooperation would be available for good and no further,” Bates said.

“He exercised extreme caution with the original draft of the Emancipation Proclamation. … He didn’t let Stanton or [Secretary of State William] Seward, or in fact any of his cabinet know when he began the first draft of the emancipation,” he added.

Invariably, Lincoln’s first visit to the telegram office came immediately after breakfast in the morning.

Upon entering, he’d often encounter Bates before he saw anyone else, and he’d greet the young man by his middle name.

“Well, Homer, what’s the news this morning,” he’d say.

With that, “he would drop into a chair at Eckert’s desk and resume work on the proclamation,” Bates said.

But not without first meditating on the well-being of a group of spiders that had taken up residence nearby.

“There seemed to be two or three families [of spiders] between the sashes adjacent to Maj. Eckert’s desk, and they usually had some kind of doings that engrossed the president,” Bates said.

The president, the telegraph operator said, had an “unaffected interest” in the spiders, and the spiders seemed to reciprocate, “performing for the president from time to time as he settled himself at Eckert’s desk,” he added.

Lincoln would comment on the changes the spiders had made in the web since his last visit — referring to the critters as “Eckert’s lieutenants,” and take note of their acquisition of flies and other insects.

“Then he’d take out of a private drawer the uncompleted proclamation,” Bates said.

“Scanning what he had already written, he would sit still for a minute or two as he buckled his mind to what he wanted to write next,” he continued.

“Another glance at the spiders, a hitch to the chair, a glance out of the window, and then, with the right words in mind, he’d write a few lines, pausing to read over the document as far as he got.

“He didn’t write much at a time and he didn’t write rapidly, but what he did write was beautifully done, with no interlineations or erasures,” Bates recalled. “After the first day or two of this kind of work, all four telegram men knew what he was doing, as he made no secret about it with Eckert, who was the guardian of the draft.

“That’s the way the Emancipation Proclamation grew,” he said. “A little at a time, with a new paragraph every day or two.

“As I said in the beginning, the spiders intermittently had his attention. What they were doing, especially as they threw out filaments and found anchorages for them … were like a general establishing of new lines of communication … and all these marvelous little things challenged Lincoln’s thought.

“What the spiders were doing seemed to lubricate the big man’s mental machinery, much as a jest or pertinent anecdote would do at other times,” Bates said.

Sixty years on, Bates said, while other memories had faded, the “thrilling drama” of the telegraph room and Lincoln’s writing of the Emancipation Proclamation there still stayed with him.

“Charles A. Dana, assistant secretary of War and later, editor of The New York Sun, said that Lincoln, in his judgment, was the least faulty of any man he ever knew,” Bates said. “I agree with him.

“[Lincoln] was the most humane, most lovable man I ever met,” he said.

Dan can be reached at [email protected] and at https://twitter.com/DanMcCue