Does Ernie Pyle Still Matter?

WASHINGTON — Ernie Pyle’s journalism career ended, literally, on the sands of a tiny Pacific island during the Battle of Okinawa.

Though Pyle didn’t live to see the end of the World War that made him a reporting superstar, nearly 80 years later, his memory and influence remain strong.

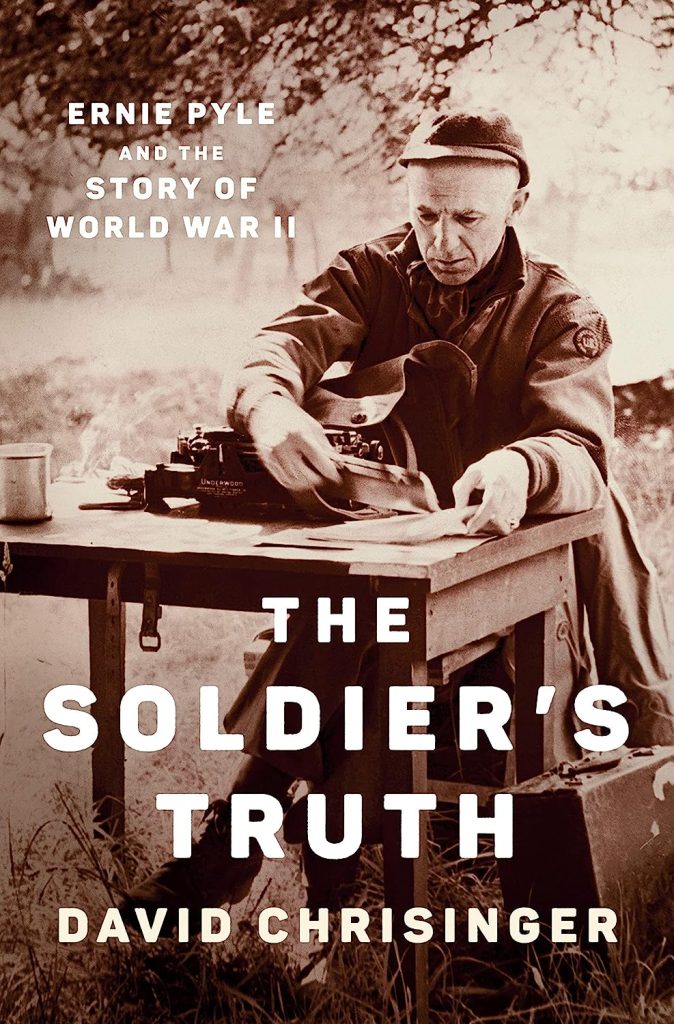

Over at the National Press Club, plans are in the works to do a special session on him this fall, and a new book, “The Soldier’s Truth,” subtitled “Ernie Pyle and the Story of World War II,” has been hailed “a beautiful reckoning” of the life and work of the journalist who put a human face on the tragedy of war for millions of readers back home in the states.

As it happens, one of the main participants in the planned NPC event and the book’s author are the same person: David Chrisinger, executive director of the Harris Writing Workshop at the University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy, who admitted during a recent interview with The Well News that he didn’t know who Pyle was when the book project kind of snuck up on him.

“I was in Okinawa, off the coast of Japan, in May 2016, doing research on my grandfather’s battle experiences when the person I’d hired as a guide to take me around began talking about Pyle, explaining that this is where he’d been killed during the battle,” Chrisinger said.

“Up to this point, I was really trying to fill in an era in my family history. My grandfather had been a tank driver during the war and had seen some really horrible battles, but he didn’t like to talk about it after the war, and details from the stories he did share were always lacking,” the author continued.

“The one thing I did know is he definitely struggled, for the rest of his life, with whatever he had experienced,” he said. “So I set out to do my own research, trying to just kind of paint a picture of what I could.”

Chrisinger recalled that Pyle’s name first came up at the very end of the tour, after he and his guide had visited all of the places where the writer’s grandfather’s tank battalion had engaged the enemy.

“He said there’s one more place I want to take you,” Chrisinger said.

They wound up at the Cornerstone of Peace, a monument commemorating the Battle of Okinawa and the role of the island during World War II.

Dedicated in 1995, it is inscribed with the names of over 240,000 people who lost their lives during the war.

“In a way, it’s very similar to the Vietnam War memorial in Washington, D.C., and just like in D.C., visitors often go and do rubbings of the names of friends and family members who were lost,” Chrisinger said.

“My guide asked if I knew anyone that my grandfather had lost in the battle, offering to look up the location of the name, and I had to admit, I didn’t know any names off the top of my head,” he said. “So my guide said, ‘Well let me show you one that you might recognize’… and that’s when he showed me the name Ernie Pyle.”

Chrisinger drew a blank.

The first thing that flashed in his mind was the story of Arthur John Rambo, whose name, legend has it, was appropriated by the actor Sylvester Stallone for his “Rambo” movies.

The real Rambo was a U.S. Army staff sergeant from Libby, Montana, who was killed in Tay Ninh province, Vietnam, in late November 1969. His name is on panel 16w, line 126, of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, where Stallone is said to have seen it.

With pop culture racing through his mind, Chrisinger asked whether “this was the guy Gomer Pyle, from the 1960s situation comedy of the same name, was named after?”

“It’s the only association I had with the name Pyle at that point, having watched reruns of the show with my dad as a kid,” he said with an apologetically sheepish chuckle.

His guide, he said, laughed as well.

Then he said, “If you don’t know who Ernie Pyle is, you’ve got some homework to do.”

Handing Chrisinger a list of books featuring Pyle’s writings, the guide told him, “If you really want to understand what it was like to be a soldier during World War II, if you really want to know what your grandfather experienced, then you have got to read Ernie Pyle.”

So, Who Was Ernie Pyle?

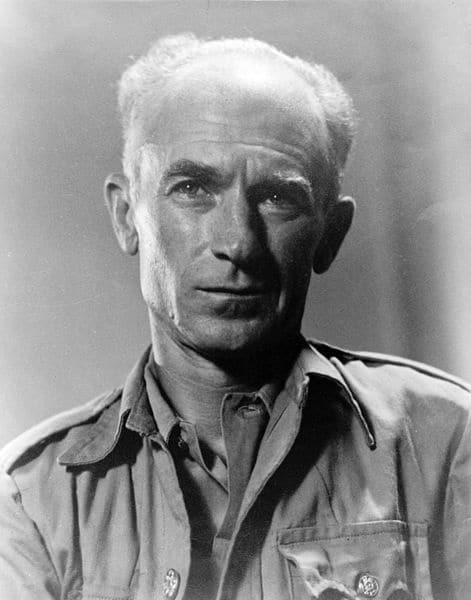

Ernest Taylor Pyle was born on Aug. 3, 1900, on what was then known as the Sam Elder farm near Dana, Indiana. His father, William, was a tenant farmer on the property, and neither he, nor Pyle’s mother, Maria, attended school beyond the eighth grade.

Though he disliked farming, Chrisinger said an abiding love of rural America never left Pyle, and that, in fact, despite later visiting some of the world’s great capitals, “he actually hated big cities.”

What Pyle did like — indeed, love — was adventure. Hoping to see the world, he enlisted in the U.S. Naval Reserve, hoping to see action in World War I. Then the war ended before he could have a hand in it, and he enrolled in Indiana University, intent on becoming a journalist.

By his sophomore year, he was working on the Indiana Daily Student, the student-written newspaper, and in his junior year, he became both its city and news editor.

Newspapering, however, took a back seat to travel in the spring of his junior year, when Pyle and three fraternity brothers dropped out for a semester to follow the university baseball team on a trip to Japan.

Low on funds, the travelers found work aboard the ship on which they traveled and the trip itself took them to a number of exotic ports, including Hong Kong and Manila.

Though Pyle returned to school that summer, he would quit for good just weeks before he would have graduated, to take a reporting job at the Daily Herald in La Porte, Indiana. Three months after that, he joined the staff of The Washington Daily News, a new Scripps-Howard tabloid.

“By the time he left school, just a semester shy of graduating, Pyle had really caught the journalism bug,” Chrisinger said. “So he tells his parents he’s leaving school to go to the Daily Herald and they were like, ‘Are you crazy?’

“And I think the way he looked at it was, ‘I went to college so I could get a job and now I have a job, so why shouldn’t I take it?’

“So he leaves school and starts working as a cub reporter. It was during this period, most Pyle enthusiasts agree, that he developed the trademark style that would make him famous — writing simply, but with an emphasis on storytelling.

“One really great piece he wrote during this period was about a Ku Klux Klan rally,” Chrisinger said. “And he just had this very … what you might call fly-on-the-wall approach … to how he did it.

“In a way, he wrote it like a letter written by someone who had witnessed an event and was relaying it to someone who hadn’t been there. It was almost as if he were thinking, ‘Hey, let me tell you about what happened.’ And that style seemed to really appeal to people,” he said.

In Washington, Pyle again started at the bottom, working as a copy boy and slowly working his way into writing headlines and eventually stories of his own.

But Pyle, now newly married, grew restless and quit his job, and proceeded to take a 9,000-mile trip around the country — all of it in a Model T Ford — with his wife Geraldine.

When their money finally ran out, in New York City, Pyle took reporting jobs at the New York Evening World and New York Post, then flew the coop again, this time to return to Washington, D.C., and the Daily News. never suspecting his career with Scripps-Howard would continue for the rest of his life.

After distinguishing himself as a reporter, Pyle became the author of the nation’s first and best-known aviation column — despite the fact he was never a pilot himself.

So popular did it become that Amelia Earhart once said, “Any aviator who didn’t know Pyle was a nobody.”

And with success came promotions. At 31, Pyle was named managing editor at The Washington Daily News, but he would soon find being chained to a desk an ordeal.

“It’s one of those typical stories, right? He was a really good reporter … and they just kept promoting him up to where he wasn’t reporting anymore,” Chrisinger said.

“And he didn’t like that at all. He really didn’t like being a manager, especially. And he had gone from writing a column about the early days of aviation — which was a real sexy topic at the time — to fixing people’s headlines. Finally, he just got burned out,” he said.

Three years after his promotion, Pyle came down with a severe case of the flu. To shake off his protracted illness, he took an extended vacation and drove to the western U.S. with his wife, filing a series of stories about the trip and the people he met along the way.

The stories proved a sensation both with readers and with the higher-ups at Scripps-Howard.

“They knocked my eyes right out,” said G.B. Parker, then editor-in-chief of the entire newspaper chain, who added that he felt they had “a sort of Mark Twain quality about them.”

Seeing an opportunity to escape his desk-bound drudgery, Pyle asked to be relieved of his editing duties and became a roving reporter, filling his own national column with human-interest stories.

The “Hoosier Vagabond,” as the column was known, appeared in Scripps-Howard newspapers six days a week, with dispatches filed from all over the United States, Mexico, Canada and South and Central America.

“It was work that really suited his personality, and for many of the years he did it, he had no permanent address,” Chrisinger said.

“He would usually pick a place from this AAA book he carried with him, stopping at the hotel in town that it recommended, and then, after getting a room, he’d go down to the local newspaper,” he said.

Once in the newspaper’s office, Pyle would befriend a reporter or editor, schmoozing long enough to ask if they knew anyone in town who was particularly quirky or had some interesting stories.

“Sometimes the question was as simple as, ‘Is there anything special about this place?’” Chrisinger said. “And what was interesting is that a lot of the time, the people who gave him tips doubted they’d amount to anything. These were local people or local places, so they were not very interesting to people who lived there.

“But for Ernie, meeting this person or going to that place or doing this thing … these would all be new experiences for him and then he’d write about it,” he continued.

While Pyle’s writing had an instant appeal, he also benefited from the fact Americans weren’t a very mobile people at the time — few traveled more than 20 miles from the place of their birth — and the Great Depression had made travel expensive.

“So people lived vicariously through his stuff,” Chrisinger said. “He wasn’t writing hard news or blowing the lid off any conspiracies … Day after day it was purely human interest stuff and he did it so well and in such a personable fashion, that people started to feel like they knew him.”

Pyle continued his daily travel column until 1942, but by that time he was also writing about American soldiers serving in the European theater during World War II.

Out of Personal Tragedy, a War Correspondent Is Born

The final years of Pyle’s self-described “roving” coincided with the ominous events in Europe that foreshadowed the onset of the war.

They also were a time of great anguish for Pyle, as his wife, who everyone called “Jerry” and who readers knew as “that girl who rides with me,” began to slip into profound mental illness.

“This was years before there was any kind of consensus on mental illness, but what happened was Jerry began to have these manic episodes and get in really, low, low, depressive moods,” Chrisinger said. “The consensus now is that she likely had bipolar disorder, but this was years before people made that diagnosis and certainly before there was any medication or treatment to help her.

“As a result, she started using alcohol to level herself out, but then she became addicted to that, and her personality changed again when she was drunk,” he continued. “That led to a series of really barbaric treatments. One was to prescribe her bromide, which led to her suffering from bromide poisoning, and then they started giving her barbiturates and opiates … I mean, they just threw everything at her because they didn’t know what to do.”

For Pyle himself, Jerry’s decline was cause for a deep, unrelenting despair. When they’d met and during the early years of their marriage, she was known to everyone as a highly sophisticated, artistic woman.

She played the piano whenever she found herself near one, and she wrote pages and pages of poetry.

When it came to Pyle’s early journalism, Chrisinger said, “there’s a lot of evidence that suggests she would retype his drafts and kind of clean them up for him.”

Pyle also is known to have repeatedly turned to his wife – particularly during their “roving” days – when he simply couldn’t find exactly the right word to express what he wanted to say.

“Ernie really thought of her as one of those people who knew the right word to use all the time,” Chrisinger said. “Like he’d turn to her and say, ‘I need a word that suggests someone is frustrated, but not angry.’ And she’d say, ‘Oh, you mean …’ And come up with the word.

“So Ernie would bounce things off her all the time and rely on her as his own personal thesaurus,” he continued. “And of course, there are also rumors that she wrote a bunch of the pieces under his byline, especially when his own depression was acting up and he wasn’t able to meet his deadline.

“So she played an undeniably large and important role in his work. She was his muse, his editor, his promoter, and his self-esteem builder,” Chrisinger said.

With his wife unable to travel with him any longer and medical bills stemming from her treatment mounting, Pyle had some serious life decisions to make. He didn’t want to leave the newspaper business, but didn’t want to be an editor and couldn’t see how he could make ends meet as a beat reporter, even one with a national reputation.

At the same time, the war was now clearly on, and he thought of getting a commission in the Army Air Corps.

“The thing is, he’s now in his early 40s, he’s like 5’3″ tall and weighs 110 pounds — he’s nobody’s vision of a ‘Greatest Generation’ soldier, if you know what I mean,” Chrisinger said.

Pyle also couldn’t help but notice the military was drafting newspaper men with the intention of making them press officers, censors or public relations people. Believing the same fate awaited him, he approached his local draft board and was told it’d be at least six months before he was called up.

“That’s when he goes to his editors at the newspaper and says, ‘Send me overseas for six months, send me to the United Kingdom,’” Chrisinger said.

“And they say, ‘Well, what are you going to do there?’ He says, ‘I’m just going to do what I did here, during my roving days. I’m going to rove from camp to camp. I’m going to find interesting people. And I’m going to tell interesting stories. Basically,’ Pyle said, ‘I’m going to write their soldiers’ letters home for them.’

“So they send him over, and the column takes off like a rocket,” Chrisinger said. “And the reason is, he’s telling people back home what they really want to know. They didn’t really care that much about military strategy and so forth. What they wanted to know on the war front was what kind of food were their sons eating? How were their husbands dealing with their separation? How are their brothers sleeping at night?

“It was all those little stories, the little truths, the putting a human face on everything. That’s what people wanted to read,” he added.

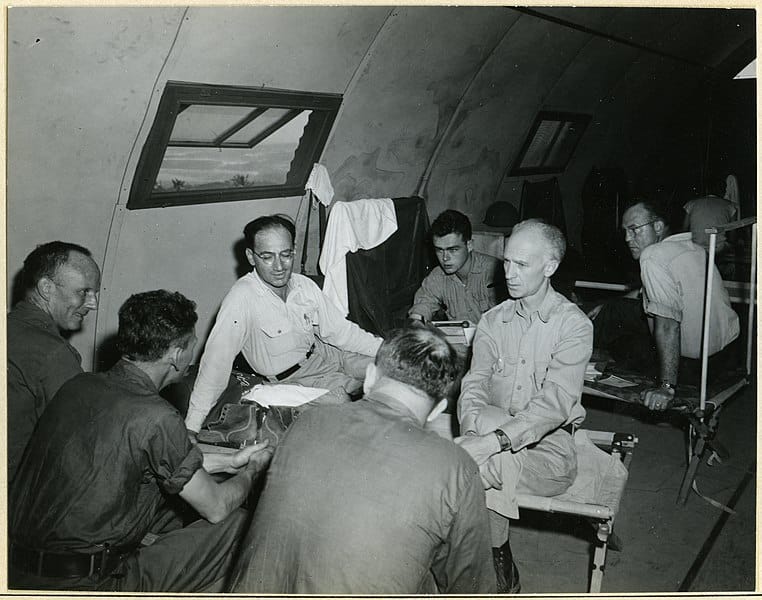

Pyle initially went to London in 1940 to cover the Battle of Britain, but then returned to Europe in 1942 as a war correspondent for Scripps-Howard newspapers.

Beginning in North Africa in late 1942, Pyle traveled with the U.S. military during the North African campaign, the Italian campaign and the Normandy landings.

Chrisinger believes that because of the nature of Pyle’s writing and the fact no one thought of him as a war correspondent, the newspaperman initially got something of a pass from a military censorship perspective.

“I think that honestly made him less of a target,” Chrisinger said. “They thought he was just writing these human interest pieces, and that there wasn’t anything in them that could give the enemy any details regarding battle plans or whatever, right.”

By the time he was initially scheduled to return home to the U.S., Pyle had built up enough of a following that his draft board agreed to give him what they called a “non-deferment deferment.”

Better to have him continue his popular reporting on the war, they reasoned, than to waste him as a government flack.

It’s at this point, Chrisinger suggested, that Pyle truly threw himself into the work of a war correspondent, and that everything about his past became the prologue to his work.

“I mean, he knew scores and scores of pilots from his days doing the aviation column, and many of them now are officers in the Air Corps. So he’s a trusted friend to these people with a rapport that goes back years and years. As a result, he got into places that other reporters couldn’t.

“He also had all of the knowledge and sense of different places that he picked up from his days roving the country, so he knows the culture of soldiers he’s talking to, he knows how they talk and the different meanings certain words have to them. In other words, he understands the nuances that go along with the places they call home. And he also knows how to blend in and be a fly on the wall,” he said.

“The other thing is Pyle is just a crazy, prodigious writer. During his days as a roving reporter alone, he wrote something like 2.3 million words. And in doing so, he’d learned — I’m thinking of a Liam Neeson line right now — ‘a particular set of skills.’

“Pyle develops skills for getting to know people, for getting them to open up to him and for making them feel comfortable even if he was writing on deadline. And he’s learned how to get to the heart of things, the essence of things,” Chrisinger said.

All of this paid particular dividends later in the war, when Pyle starts to tell his readers back home about some of the harder truths of the war.

“By then, Pyle is the best possible person to deliver those messages because he’s built up that trust and that rapport with his readers. So for instance, after D-Day, Pyle writes that yes, we got on the beach at Normandy, but let me tell you what that cost us. … And he did. And he continued by saying, ‘And let me remind you, this war is not over and a lot more people are going to die.’

“People needed to hear that,” Chrisinger said. “And when politicians tried to assure people that ‘we’ll be home by Christmas,’ Pyle was the one writing, ‘No, that’s not true.’”

Pyle spent more than 28 straight months in the European theater of the war, far longer than any soldier. In September 1943, he returned to the U.S. to recuperate from the stress of combat and to resume caring for his wife.

While back on U.S. soil, he advocated the soldiers in combat should get “fight pay,” just as airmen received “flight pay.”

In May 1944 the U.S. Congress passed a law that became known as the Ernie Pyle Bill. It authorized 50% extra pay for combat service.

Pyle returned to Europe in time to witness the liberation of Paris, France, in August 1944, but would confess to readers that his spirit was “wobbly” and “my mind is confused.”

He also confided in readers that he feared if he “heard one more shot or saw one more dead man, I would go off my nut.”

In January 1945, he reluctantly accepted what would become his final writing assignment, covering the war in the Pacific.

It was here, while covering the U.S. Navy and Marine forces, that he finally came into open conflict with the military brass.

As the war continued, Pyle began to write unflattering stories about the Navy, prompting complaints from the service and his fellow correspondents.

His heart just wasn’t in it anymore, he told a number of people, and yet he pressed on, to Okinawa.

Book Wasn’t First Intention

Chrisinger said he had no intention to write a book about Pyle when he accepted his guide’s challenge to learn more about the long-dead journalist.

“It was more a case of the stars eventually aligning and saying to yourself, ‘Well, this is a book that has to exist.’”

Immediately after returning home from his trip, Chrisinger pitched the story he wrote about his grandfather and his war experiences to The New York Times, which then had an “At War Column.”

The Times liked the story and bought it, and after it got a good reception from readers, the editor asked if he wanted to continue on as a contributing writer.

It was an auspicious invitation. On its agenda for 2019, the newspaper planned to do a yearlong series to mark the 75th anniversary of the end of the war.

“As they were planning this series, they were trying to find pieces that maybe had been lost to history or had never been fully reported or some myth that needs to be corrected … and when I learned of this, I immediately thought, ‘I want to write about Ernie Pyle’ … because he fit the definition. He was lost to history … or at least lost to me. So my pitch was, ‘I want to do a story on the column he wrote after D-Day, because it is just so incredible,’” Chrisinger said.

“I intended to do kind of a ‘story-behind-the-story’ piece. And the editor liked the idea.” The only problem, the editor didn’t have enough money in his budget to send Chrisinger to Normandy.

“But he did have enough to send me to Dana, Indiana, Pyle’s hometown. So I went to the Ernie Pyle museum there. I went to his childhood home. I went to the archives. I interviewed experts … you know, just did the normal journalism stuff … and the piece I wrote from that, I later found out, had over a million online views the very first day.

“The paper itself took note of that, and ran the piece in the actual physical paper a couple of days later, across both pages of the centerfold,” he said. “Shortly after that, I got a call from the guy who is now my publisher and he said, ‘I read your piece on Pyle and some of your other pieces, and if you ever want to do a book on Pyle, I’m interested.’”

The phone call led to a meeting with the publisher asking for a pitch.

“He said, ‘There’s been other biographies of Pyle, what are you going to do that’s different?’” Chrisinger remembered.

He said he immediately thought of the book “Confederates in the Attic” by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Tony Horwitz, which asks the basic question, ‘Why do people still care so much about the Civil War?’ and ‘And why have so many of the root causes of the war never really gone away?’

“Horwitz decided to go in search of his answers by becoming a Civil War reenactor and traveling all of the South and going to all the battlefields and museums and talking to all the experts,” Chrisinger said. “I just love that kind of writing and I said, I’d really like to do a similar thing with Pyle, retracing his steps through the war, speaking with people that might have known and remembered him, and to discuss the war with people who lived in these various places at the time and ask them what it was like.

“And after a lengthy pause, during which I thought to myself, ‘You blew it,’ he finally said, ‘Yeah, full speed ahead. Let’s do this.’”

Sudden Death on a Wednesday Morning

Ernie Pyle arrived at his last battle scene striding ashore with the U.S. Army’s 305th Infantry Regiment, 77th Infantry Division, on Iejima (previously romanized in English as Ie Shima), a small island just west of Okinawa.

Though the landing was successful, the island itself had yet to be cleared of enemy soldiers.

That night, the newspaper man The New York Times referred to as the “chronicler of the average American soldier’s daily round,” hunkered down with the troops.

The next morning, after enemy opposition had supposedly been mopped up, Pyle climbed into a jeep with Lt. Col. Joseph B. Coolidge, the commanding officer of the 305th, and three additional officers.

They were headed for Coolidge’s new command post when the vehicle suddenly came under fire from a Japanese machine gun.

Everyone ran for cover in a nearby ditch and stayed there until the shooting stopped.

“A little later Pyle and I raised up to look around,” Coolidge said later, in an official report of the incident.

Some distance away, a Japanese sniper saw the slight, graying reporter come into view. It was 10:15 a.m., Apr. 18, 1945.

“Another burst hit the road over our heads … I looked at Ernie and saw he had been hit,” Coolidge said.

A .30-caliber machine-gun bullet had entered Pyle’s left temple just under his helmet, killing him instantly.

In the command post, which was just 300 yards away, Army photographer Alexander Roberts witnessed Pyle’s last moment and, due to continuing enemy fire — crawled to the scene.

Once there, he recorded Pyle’s death with his Speed Graphic camera. His risky act earned Roberts a Bronze Star medal for valor.

Later that day, Pyle was buried among soldiers on Iejima. Shortly, members of the 77th Infantry Division erected a monument at the site of his death.

“At this spot the 77th Infantry Division lost a buddy, Ernie Pyle, 18 April 1945,” it reads.

“The G.I.s in Europe — and that means all of us — have lost one of our best and most understanding friends,” Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower said when he heard the news.

Back home, the newspapers reported that Jerry Pyle took the news of her husband’s death “bravely,” but her health declined rapidly in the weeks and months that followed, and she died from complications of the flu while staying in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in November 1945. The couple had no children.

In 1949, Pyle’s body was moved to the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific at Punchbowl Crater, near Honolulu, Hawaii.

Talking about Pyle’s death, Chrisinger again turned to pop culture.

“There’s a line, an old quote from ‘Batman,’ that says something like, ‘You either die a hero or you live long enough to be the villain.’ Well, Ernie died the hero,” he said.

Pyle’s Legacy

When The Well News first reached out to Chrisinger, a new crop of summer interns had just arrived at its offices, and the idea of reaching out to the author was premised on a simple question with them in mind:

Just what does Ernie Pyle have to teach young journalist today? What, if you will, is his legacy?

“What jumps out at you from his pieces is his ability to state things simply that are not simple to state,” Chrisinger said. “He found ways to boil down these big existential questions into specific scenes and events with very specific characters. And so he sort of found the specific in the universal and the universal in the specific.

“He also had this ability to really distill the essence of something in a few important details,” he continued. “This is something that I teach my students in my class on public policy writing. All the research shows that your story will stay with people longer if you appeal to their sensory imagination. That’s why novels are so popular. And that’s why TV works.

“So how do you appeal to these sensory details? You learn to see the essence of things and express them with just a few details. You don’t hit somebody over the head with a laundry list. You have to be selective … and Ernie Pyle was amazingly good at being selective.

“Those are a few of the things I think any journalist or professional communicator would take away from reading Ernie today,” Chrisinger said.

“The other thing is, if you were inclined to sit down and dissect his writing and see what makes it work, you’ll find that there are a lot of different tools he uses to make his work accessible. Ernie was a sophisticated guy who could speak very plainly … and in a way, that enabled him to speak on multiple levels to people. He’s very similar to John Steinbeck in that respect. No matter what level they’re reading his piece on, they’re going to get something out of it.

“The other thing is something we mentioned before, Pyle’s ability to put a human face on things that seem very abstract,” Chrisinger continued.

“I mean, especially writing about something like a war. Here he’s writing for millions of people who have never had these experiences before, who don’t know how to contextualize it, who don’t know how bad it is. And yet he finds really creative ways to communicate these things so they really do understand it. And he does it by being aware of the effect he wants to have on the reader.

“For instance, there’s a piece in which Pyle documents a stroll along a beach after a battle and he gives a record of things he saw washed up in the surf. Now, he doesn’t just talk about rifles and grenades and helmets … he also mentions things like combs, and letters home that will never be sent, and a pocket Bible, and a razor and a toothbrush … inanimate objects that suddenly come to represent great loss. And as a reader, you’re like, ‘Oh my God, these used to all belong to people who aren’t here anymore.’ You know what I mean?”

Chrisinger then uses a phrase in regard to Pyle that journalists the world over have heard countless times.

“He found a way to do a lot more showing than telling … Where people felt like they were there and had experienced it for themselves,” he said. “Pyle could make his readers see what he saw and hear it and feel it and smell it. And that’s an incredible skill set to have. It’s so powerful, and the power remains, even in reading those pieces today.”

One might be tempted to say at this point, “All well and good … but Pyle was writing about life and death. What does he have to teach the average beat reporter?”

For the answer, Chrisinger turned to Pyle himself, who, as managing editor of The Washington Daily News, once gave an impromptu speech to his staff.

“What he told them was that the important stories are all hiding right under your nose,” Chrisinger said. “What he was trying to address was this belief among his reporters that all the best stories get scooped up, and that unless you’re first on the beat, you’re just not going to get it.

“Their mindset was, ‘Get there first, get the copy out first,’ and you know, I hear echoes of that today from reporters who say, ‘I’m expected to do six stories a day.’ The emphasis is constantly placed on being the first to report everything. That’s paramount.

“What Ernie Pyle would say, I think, is, ‘No, you’re missing it. There are big stories. And then there are follow-up stories. And then there are human interest stories. There are all these other ways of approaching big meaty topics and you don’t have to be the first one on the scene or the first one to get it out.

“Ernie Pyle was a proponent of the idea that there are stories lurking around every corner and you just have to talk to people to find them,” Chrisinger said. “Going back to the story I mentioned a moment ago, about the aftermath of the battle on the beach. That was Ernie’s day after D-Day story, which he wrote after missing out on being at the landing.

“Had he landed with the troops, he would likely have had the blood and guts story everybody else had. But he didn’t land on D-Day, he arrived on the scene the next day, and I’m sure he walked around for 24 hours thinking, ‘I just missed the story of the century. What am I supposed to do?’

“Well, what he did was talk to everybody, and then walk to the beaches, and suddenly he’s like, ‘Oh, this is the story.’ It’s not the blood and guts and the death and whatever, it’s the stuff in the surf. This is the story.’ But he probably wouldn’t have seen that if he had landed the day before, because nobody else who landed the day before saw it.

“So Ernie Pyle was good at finding the story even when he wasn’t there for the story. And I think that’s something all journalists can take a lesson from,” Chrisinger said.

Dan can be reached at [email protected] and @DanMcCue