Patrick Caddell’s Last Race

He sought to further the presidential ambitions of both Joe Biden and Donald Trump. Now the late pollster and political advisor’s former clients are going head to head one last time.

CHARLESTON, S.C. — To find Patrick Caddell, the self-taught political pollster who traversed an arc in presidential politics that carried him from Sen. George McGovern to Donald Trump, one needs to be blessed with a little luck and a penchant for persistence.

A native of Rock Hill, South Carolina, he rests now in a family plot in Charleston’s historic St. Lawrence Cemetery, a few yards from where the solid ground gives way to an untamed Lowcountry marsh.

“Good luck,” a cemetery employee said as she pointed a visitor toward the “new” part of the cemetery.

“They’ve been burying people here since the 1850s, and back then they didn’t keep the kinds of records we do now,” she said.

“It’s safe to say we don’t know everyone who’s out here, and there’s no way we ever will, beyond the name on a family plot,” she added.

“I’m looking for a newer burial,” the visitor said, scanning the landscape. “I’ve even got the coordinates, the section, the plat, and even his grave number.”

“Well, I’ll try to help you,” she said with a hint of resignation in her voice and pity in her eyes.

“The trouble is, the sections and all are no longer marked,” she explained.

Like all old Southern cemeteries, the sun-drenched grounds were a cacophony of mismatched, weathered stones and the occasional statue of a grieving angel, surrounded by water oaks picturesquely hung with Spanish moss.

Just inside the gate and smack in the middle of the intersection of two paths leading directly into and around the cemetery stands a wrought iron cross.

It’s the tomb of one Christopher Werner, who immigrated from Germany and initially went into the carriage-making business in the pre-Civil War city. He later opened a blacksmith shop, and then a foundry and one of his first jobs was creating the iron gate that surrounds the burying ground to this day.

In December 1861, it was one of the few man-made items in the area that survived a great fire that swept through the city, destroying everything in its path and causing even a visiting Gen. Robert E. Lee to flee his room in downtown’s Mill House Hotel.

So proud was Werner in his robust handiwork that he decided never to part from it, and since his death in 1875, he hasn’t.

But that was neither here nor there on this particular morning. Just a bit of trivia to ward off a touch of spookiness.

Finally, after making a beeline to the back of the cemetery, a straight shot of 100 yards or so, we found our man in an old family plot, under the shade of an oak whose girth suggested it had been on this land as long as the cemetery, maybe longer.

“Not a bad place to be if you absolutely had to be somewhere forever,” one thought.

We paid our respects and made the sign of the cross before pushing aside a stray strand of Spanish moss that had fallen to the ground.

Seeing his name in full on his tombstone, it seemed out of place given how many times we’d seen it sandwiched between the names of Dee Dee Myers and Marlin Fitzwater in the closing credits of “The West Wing,” for which he’d been a consultant.

Suddenly, a line from a different Hollywood creation popped into our head.

The movie was Clint Eastwood’s “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil,” from the book by John Berendt.

“To understand the living,” the voodoo queen Minerva says in a memorable late-night graveyard scene, “you got to commune with the dead.”

In a way, it was exactly why we were here.

A Last Hurrah?

Truth be told Patrick Hayward Caddell had been much on our mind as the 2024 presidential contest wound its way from the snows and frigid temperatures of Iowa and New Hampshire to the much balmier South Carolina.

Tucked into our carry-on bag was a worn copy of Hunter S. Thompson’s “Fear and Loathing: On The Campaign Trail ‘72,” a book that brought a fair amount of attention to the young pollster when it was published the year after the contest.

Thompson, fresh off the success of his Gonzo classic “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,” agreed to move to Washington, D.C., in his role of national affairs editor for Rolling Stone, and spent the better part of the next year on the road, covering mainly the Democratic primaries.

Feeling a disdain that often crossed the line into outright hostility for the two perceived front-runners in the race, Sen. Ed Muskie, of Maine, and Sen. Hubert Humphrey, of Minnesota, Thompson soon decided McGovern was his man.

It was Caddell who knew before anybody else that McGovern had a lock on the nomination, and it was Caddell who later knew that McGovern would suffer a historic drubbing in the general election.

In the end, President Richard Nixon won reelection in a landslide, taking 60.7% of the popular vote and carrying 49 states while also becoming the first Republican to sweep the South.

McGovern, meanwhile, after weeks of missteps, took just 37.5% of the popular vote.

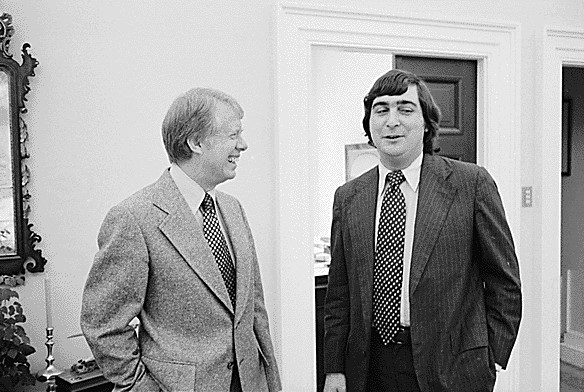

But Caddell came away an anointed “boy genius.” Four years later, he would help make former Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter the next president of the United States.

Other races with Democratic contenders would follow, but none ever proved as successful as his work with Carter. Howard Dean, Gary Hart, and even Sen. Joe Biden paid for his services.

Though his type-A personality often led to volatile relationships with bosses and colleagues, his bust-up with Biden was particularly brutal.

After, Caddell pronounced himself largely finished with active engagement in politics, but there was one last white whale to pursue.

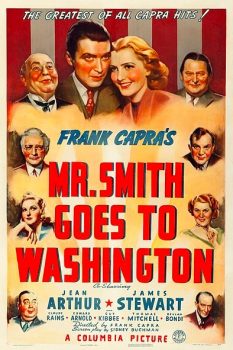

Caddell’s Moby Dick was “Mr. Smith,” an outsider candidate who would be elected to office in Washington and clean up the broken federal system.

His inspiration was “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,” Frank Capra’s 1939 Hollywood classic starring Jimmy Stewart as Jefferson Smith, the leader of Boy Rangers in his home state who naïvely accepts a gubernatorial appointment to the U.S. Senate believing he’s being sent there solely to serve the interests of his constituents.

Initially, the Washington press corps and others take him for a rube and a bumpkin, but his idealism and utter incorruptibility in the face of intense pressure from party bigwigs and special interests raised him to a whole new level of populist nobility.

It was a theme he would return to again and again over the course of his career, and his quest, much to the surprise of his old Democratic friends, led him into the orbit of Donald Trump.

Though Caddell would never formally work for Trump or his presidential campaign, he quickly became a trusted advisor with direct access to the candidate and later president.

One of the great frustrations of any political junkie is to share the same relative space with a heavyweight and yet not quite get to meet them. That was our story with Caddell.

We knew his name. We heard him mentioned in certain circles in and around Charleston, but there was never the right professional reason to reach out to him. And then, on a February Saturday in 2019, he was gone. Struck down by the complications of a stroke nobody saw coming.

And though he’s now five years gone, the prospect of a Biden/Trump rematch in November gives Caddell’s work and political philosophy a new relevancy. This, no doubt, is each man’s last race for the presidency. In a way, it’s the last race for the White House that will have Caddell’s fingerprints all over it.

Disliked Math Class but Loved Polls

Patrick Hayward Caddell was born the son of a U.S. Coast Guard officer.

His father Newton’s profession necessitated frequent moves to coastal communities, one of which was Falmouth, Massachusetts. It was there, on the cusp of his teens, that Caddell became enamored with the Kennedys.

Later, he would recall how he, his father and his mother, Janie Buns Caddell, would drive to Otis Air Force Base on Cape Cod to greet President John F. Kennedy on his trips home to Hyannis Port, Massachusetts.

Though Kennedy was an inspirational figure, Caddell always maintained it was the more outwardly tenacious Bobby Kennedy, who was his true hero.

By Caddell’s high school years, however, John F. Kennedy was dead and Bobby would have to inspire from a distance.

By then, the Caddell family had moved on to Jacksonville, Florida, where Caddell excelled, becoming a member of the National Honor Society and eventually, president of the student body at the city’s Bishop Kenny High School.

Ironically, the one class he later said he didn’t much like was math class due to its often rote nature, but he found he loved — and had an extraordinary talent for — the practical application of numbers.

It was this love of what numbers could tell you that inspired him in the fall of 1967 to develop a stunningly accurate model to project election winners.

While accounts vary, the most likely have him showing up at the county election office on election night 1967 and astounding candidate after candidate with errorless predictions of whether they’d won or lost, long before the votes were counted.

The performance by the young man caught the attention of state Rep. Fred Schultz, of Jacksonville, who was about to assume the position of speaker of the Florida House of Representatives.

Schultz hired Caddell and almost immediately assigned the math protegee one of the thorniest tasks confronting the political elite of northeast Florida, the long-discussed consolidation of the Jacksonville City and Duval County governments.

While others worked on the new city charter, it was Caddell who found a way to draw district boundaries for the new city council that everyone — including opponents of consolidation — could live with.

Legend has it he drew the map overnight, carefully preserving the district of the first Blacks elected to the old city council without resorting to blatant gerrymandering.

Schoolmates would tell future interviewers that Caddell “has a certain style of always looking out for number one” and showed “a certain drive that was beyond the rest of us.”

Many attributed it to his early brush with the Kennedys and they were probably right. He certainly was an adherent to the Bobby Kennedy line that ended with “Others dream things that never were and ask why not?”

Harvard and the Uninvited Tenant

The summer of Caddell’s senior year at Bishop Kenny, his father announced his intention to retire to Charleston, South Carolina.

Caddell didn’t want to go. Instead, he showed up on the doorstep of Schultz’s home, suitcase in hand.

Schultz, who was genuinely fond of Caddell, thought he’d stay a few weeks, maybe the summer, before going off to Harvard. But Caddell never really left, going back to Schultz’s large river front home for every holiday and school break.

Years later, Caddell would explain that he came to feel he had “two families, in a sense,” and that time spent with one didn’t mean he wasn’t a loving member of the other.

Schultz wasn’t done playing a pivotal role in Caddell’s life. As his young protege prepared to graduate, Schultz guaranteed a $25,000 loan so he could start a polling business with two friends.

A short time later, in the autumn of 1971, a mutual friend introduced him to Gary Hart, then the manager of George McGovern’s presidential campaign.

The introduction led to a contract job for the campaign; $500 for a quick-and-easy poll in New Hampshire, but as the McGovernites soon found out, there was a surprising depth to what Caddell could pull from the numbers. More work for the campaign followed.

No one ever realized that the consultancy they’d hired was operating out of Caddell’s dormitory room.

“It really seemed like I’d landed in a bed of roses,” he said of the experience of bouncing between Harvard and the McGovern campaign during an interview later with NBC News. “I would leave Harvard, fly to some primary state, do these interviews and help run the campaign.

“It was extraordinary fun, but I didn’t plan or aspire to it. I just thought that’s the way it was supposed to be, I guess,” he said.

Soon, though Caddell preferred to officially remain a contractor, the young pollster from Florida by way of South Carolina and Harvard, was one of McGovern’s most trusted advisors.

The truth was, he was already sophisticated beyond his years. While at Harvard, he had done a great deal of his thesis work on the changes that were then happening in Southern politics, changes that enabled former Alabama Gov. George Wallace to become a real factor in two presidential campaign cycles.

Caddell had thought long and hard about the short- and long-term implications of these changes and began formulating a set of theories revolving around the “outsider” candidate.

Then he met Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter.

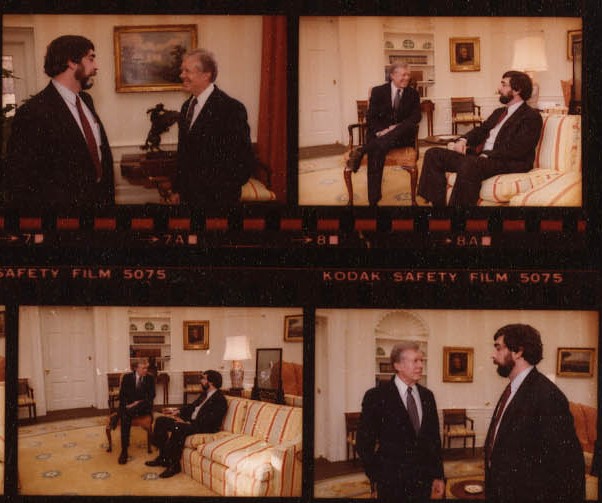

“I first met President Carter during the McGovern campaign,” Caddell would say in an April 1982 interview at the Miller Center of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia.

“I was just out of college … working for the McGovern campaign as his pollster, and in June 1972, prior to the convention, we made a swing through the South,” Caddell said.

The swing took the campaign to Carter’s government mansion. Up to this point, anticipating his own run for the White House in 1976, Carter had been one of the leading members of the stop-McGovern effort being waged by establishment Democrats.

The meeting was intended to cement a truce between Carter and McGovern, but when the future president learned of Caddell and his Harvard thesis, he insisted the pollster be invited to join them.

“We all talked about politics and the political situation, and he and I and a few other people sat up until about three o’clock in the morning talking about Southern politics and his election and the country. We got along very well.”

By early 1976, after intermittent work together in between, Caddell was Carter’s campaign pollster, and as Caddell would ruefully point out over the years, the only person working on the campaign at that point who had any experience in national politics whatsoever.

Best of all, in Carter he had the perfect subject to test his theory that voters were hungry for an outsider who could fix “what was wrong with Washington.”

While Caddell obviously didn’t invent Carter’s image as a populist peanut farmer from the South, he honed it to such a fine point for the voters that they almost overlooked the fact the governor had, while in the military, extensively studied nuclear science and power plant operation.

As the Carter campaign moved from primary to caucus to primary, Caddell repeatedly used his polling, among other things, to determine the depth of alienation and level of anger among various subsets of the electorate.

Carter’s election elevated Caddell into the operative’s stratosphere and turned him, for a time, into a celebrity in his own right.

He escorted Christie Hefner, daughter of Playboy publisher Hugh Hefner, to the inaugural ball, and soon set up house, so to speak, with then-White House Communications Director Gerald Rafshoon, in the pool house of former Miss America Yolande Fox’s home in Georgetown.

Fox, a nonconformist who refused to pose for cheesecake photos after her 1951 pageant win and later become better known as a civil rights activist, turned a blind eye to the antics of her two young tenants.

In no time, thanks largely to his refusal to join the Carter administration and be subject to government restrictions, his private consultancy was grossing $3 million a year with clients ranging from the retailer Sears Roebuck to Saudi Arabia.

But if Caddell was having the time of his young life, relishing his direct access to the new president and his role as sounding board, he quickly grew concerned that the Carter White House was losing its way.

“My role inside the White House was a very amorphous and undefined one,” Caddell told his interviewers at the University of Virginia.

“I would come in on particular issues, particularly when there were speeches involved or large policy movements. … Occasionally, I would be involved in discussion on substance,” he said.

Caddell, to his peril at times, saw his role as one of offering criticism in the context of his strong relationship with the president. But his advice and candor could and did touch a raw nerve, and it often landed him in Carter’s doghouse.

Caddell’s chief concern was that once elected, the president had become encased in the “bubble of the White House” and had begun to lose his “sharpness” and “the perception of why he had been elected and what he had been elected to do.”

“My theory [during the campaign] was that if the country was looking for someone who was best qualified in terms of the experiences of government and understanding the machinery of government, then Carter would lose because he was obviously the least qualified person,” Caddell said in Charlottesville.

“If you go back and look at those speeches that he gave early in the campaign, he would talk about the damage to the country, its psychology. He talked about what had happened to government and politics and how isolated Washington had become from the people,” he continued.

“Essentially, what he was running on in the campaign was that the country had been psychologically devastated by the previous decade of events,” Caddell said.

“He was offering himself as a healer of that, something that was not inconsistent with his own personal background. He had a very deep feeling about this. This was not a campaign tactic.”

Later in the same interview, Caddell offered another of his thoughts on the presidency.

“I think you can view historically the president’s role. I think it’s based on historical circumstance and disposition,” he said. “Usually people are in office not by accident, but because they in fact meet some need of the public.

“A president tends to be either the leader of the government or the leader of the society. That’s the whole duality problem of being chief executive and head of state. There are very few presidents you could point to historically who could fulfill both roles well,” Caddell said.

“I think if you use that rough rule of thumb, you would see John Kennedy was most successful because he was viewed as a leader of society, which was why I think he suffered so much in retrospect in terms of his accomplishments or lack thereof as a leader of the government.

“Lyndon Johnson was the exact opposite,” Caddell said. “LBJ was much more the efficient implementer of programs, and running the executive branch and what have you and much less of the other.

“It seemed to me that Carter was elected in fact to lead the society. That was the mandate that people had given him. He was to make things better, not just in a governmental sense, but in a general psychological leadership sense. He was also supposed to run the government, but it was the secondary concern.”

Reflecting on these conversations years later, Caddell admitted he believed he had “a particular relationship with the president” that protected him from permanent banishment from the West Wing.

“I used to argue with the president that I thought he was a different person than when he had gotten elected,” Caddell recalled. “He had changed in the office, and I did not personally think for the better. But you have to understand I was sometimes hysterical in these times. You just generally don’t go around saying these things to presidents.”

He then went on to express a bit of remorse about the more heated of these conversations.

“The president is just like any other person,” he said. “When you’re up to your neck in alligators, it’s hard to remember your purpose was to drain the swamp,” he said. “And here I kept coming in and asking, ‘Why have you not drained the swamp yet?’

“And this while he’s sitting there in the Oval Office surrounded by all kinds of things, foreign policy problems and so on that I didn’t know anything about. And yet here I was hammering him. And sometimes we would get into strained situations.”

Caddell later set down some of his beliefs in an early memo that morphed, to Carter’s eventual regret, into the so-called “malaise” speech, in which the president told the nation it was in danger of wallowing in a crisis of confidence.

“It is a crisis that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will. We can see this crisis in the growing doubt about the meaning of our own lives and in the loss of a unity of purpose for our nation,” Carter said.

“The erosion of our confidence in the future is threatening to destroy the social and the political fabric of America,” he said.

The speech was not the one Carter had intended to give — he wanted to talk about solutions to the energy crisis the nation was facing at the time — but Caddell had pushed for something bigger, broader.

Caddell’s proposal faced stiff opposition, including from Vice President Walter Mondale, who called the pollster/advisor’s suggestion “crazy.”

Caddell prevailed in the end only after passing his memo to First Lady Rosalynn Carter. Later, during a Camp David summit with White House officials to discuss domestic policy, she pressed her husband to act on it.

“When you become fairly unsure, there’s nothing like being a leper for a while to make you wonder about your own judgments,” Caddell said, but he admitted he was desperate.

“The House was falling apart, the government was falling apart. There was a widely held pessimistic view about the structural problems of the government and with structural solutions,” he said.

Caddell also admitted he was looking forward — constantly — to Carter’s 1980 campaign for reelection.

“We kept wanting to have a campaign about the future but we had two problems. One was that the government, which we kept counting on politically to help the incumbent make people want to vote for us, was constantly turning up bad news. Things weren’t happening. And we were desperately trying to orchestrate some effect to play on being the incumbent,” Caddell said at the University of Virginia.

“We weren’t getting much out of that, and secondly we were having a hard time with shaping the future,” he said.

The initial response to the July 15, 1979 speech was quite positive. Carter’s poll numbers jumped 11 points in its aftermath and the White House was flooded with calls and letters of support from ordinary citizens.

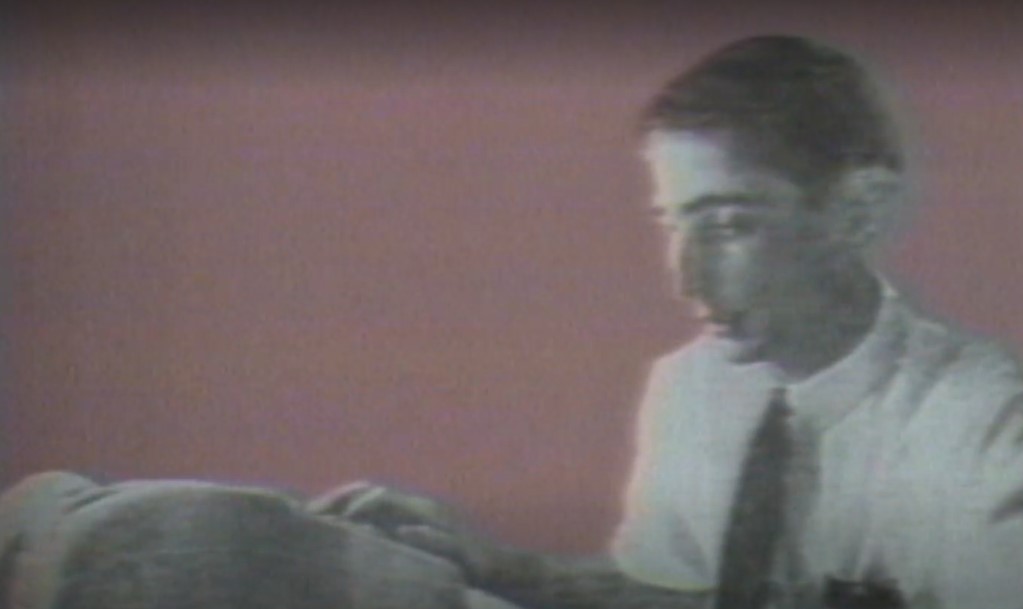

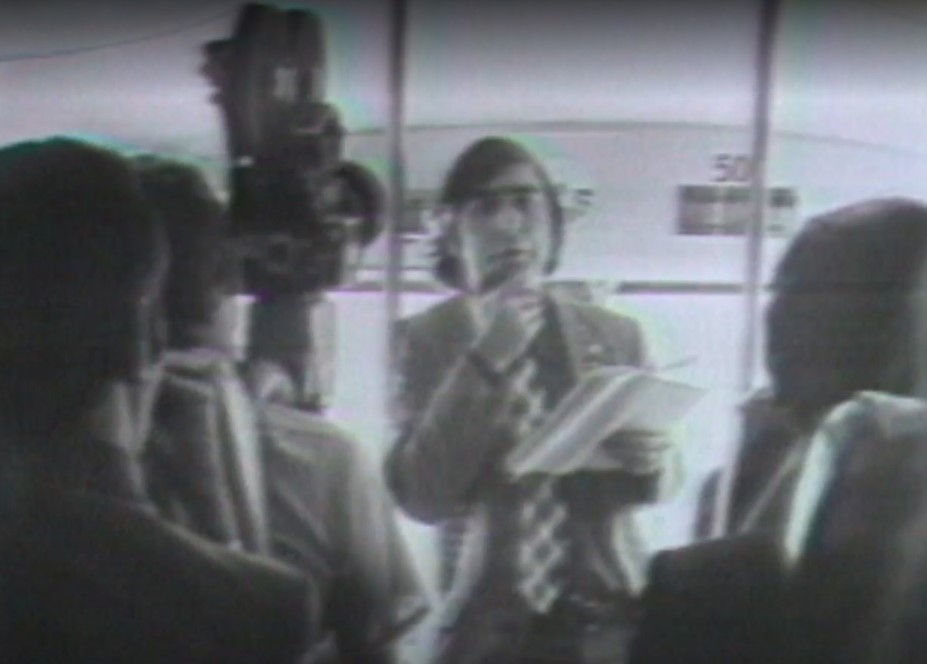

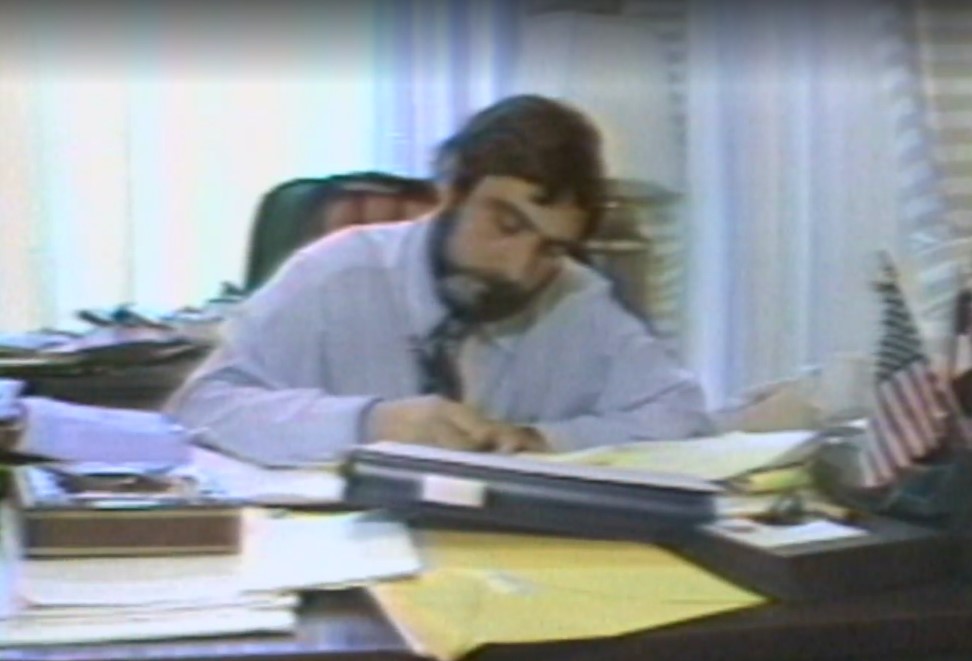

NBC Nightly News even did a five-minute segment on Caddell, reinforcing his image as the man with the president’s ear and a young man to watch.

During an interview for the piece in the fall 1979, Caddell would tell Bob Jamieson of NBC News that he believed there was more to his having the president’s ear than simply having helped in getting him elected three years earlier.

“I would not want to go through life being stereotyped as ‘Well he does polling.’ ‘He does number crunching.’ ‘That’s all he knows,’” he said. “I mean, I think I have a broader intellect than that. I have a great love of history. And I have a love of the synthesis of conceptual ideas in terms of the questions we have as a society. And I would hope people would point to those as a broader definition for why the president listens to me or doesn’t.”

But the good feeling surrounding the speech and the public’s response to it would not last.

Taking Caddell’s emotional memo to heart, Carter rashly fired his entire cabinet two days after giving the speech.

“It was Armageddon,” one presidential adviser told The New York Times.

With that, Carter went from a momentary champ to chump, and would, for the remainder of his presidency be saddled with the image of someone punching above his weight, barely able to manage, let alone lead the country.

Ronald Reagan would go on to win a decisive victory, beating Carter in 44 of the 50 states and garnering 489 electoral college votes to the incumbent’s 49.

After the White House

Following Carter’s loss, the suddenly unmoored pollster began to seek out a new candidate to guide to the White House.

His first choice was former astronaut, American hero and then-Sen. John Glenn, of Ohio, but Glenn initially believed Sen. Ted Kennedy would run in 1984 and opted out of running against him.

Kennedy would later announce, in late 1982, that he would not seek the presidency and Glenn did mount an unsuccessful 1984 campaign without the involvement of Caddell.

Not content to sit on the sidelines, Caddell continued to search for his ideal candidate; the hypothetical candidate “Candidate Smith.”

Political scientist Kendra Stewart, who worked closely with Caddell years later at the College of Charleston, described this “Candidate Smith” as someone who put people over politics, who would work to get money out of the political equation, who was not overly partisan and who was generally appealing to voters.

“Pat was always wanting someone who was willing to come in from the outside and clean up our broken system,” Stewart told The Well News.

Over the next few months following Glenn’s rejection, Caddell reached out to then-Sen. Joe Biden, Sen. Chris Dodd, of Connecticut, and former Arkansas Gov. Dale Bumpers, all of whom told the pollster they were sitting 1984 out.

To many in Washington, it seemed like Caddell was getting his comeuppance for his well-established reputation for being difficult.

Then, at what must have seemed like the 11th hour — the winter before the 1984 election cycle would begin — Caddell got a phone call from Sen. Gary Hart, his old friend from the McGovern campaign.

Hart at the time was probably as little known nationally as Carter had been in 1975. Caddell advised the senator to focus on the Iowa Democratic Caucuses as Carter had, to build some momentum.

The advice proved salient. Though Mondale would win the caucuses, Hart garnered a respectable 16% of the vote, setting himself up as a contender. Two weeks later, the Colorado senator shocked nearly everyone but Caddell by beating Mondale by 10 percentage points.

What was then largely a two-man race extended into June before Mondale finally secured the nomination.

Many in the Hart camp took little solace in coming from nowhere and almost grasping the nomination.

“Losing wasn’t as bad a memory as having had to work with Pat Caddell,” Oliver Henckel, Hart’s 1984 campaign manager told The Washington Post.

Other staffers told stories of Caddell belittling the campaign, alienating campaign workers and in one instance, going “berserk” when Hart was given a speech he didn’t approve of.

“He [was] … screaming profanities,” speech writer Mark Green said. “It was humiliating.”

For his part, Caddell said the incident never happened.

Among the most prevalent complaints was that Caddell was aloof when it came to campaign hierarchy. Rather than attending campaign meetings with staff, he insisted on only dealing with the candidate himself.

Despite the speed with which these stories were making the rounds, the Mondale campaign reached out to Caddell in the final weeks ahead of the November election.

By this time, Reagan held a large lead in the polls and the two candidates were preparing for the first of two 90-minute televised debates.

In the Reagan camp, the approach was simple — just making sure the president didn’t make any noteworthy mistakes. If they succeeded, the thinking went, Reagan could coast through what remained of the campaign.

Things were tougher for Mondale. His job was to dissuade the public of the notion that Reagan’s reelection was a foregone conclusion.

Caddell advised Mondale to try to convince voters to look beyond Reagan’s personal charisma and consider the consequences of his policies in a second term.

He also told the former vice president he should lighten up, and use more subtle reprimands and even a compliment or two to keep Reagan off balance.

The strategy initially worked and Mondale began gaining on the president in the polls, but media coverage, particularly in The New York Times, angered longtime campaign staffers who felt the famous pollster had merely swept in to grab all the credit.

Caddell would later attribute his gnarly reputation to three factors. One was his anti-establishment ideas; two was simply professional jealousy, and three was sometimes he did act badly.

“I made some real mistakes,” he said.

But recognizing his own faults didn’t mean he always reined them in. Coming off his work with Mondale and Hart, he formed a polling and consulting business with Robert Shrum and David Doak, two other heavyweights in Democratic circles.

Three years later, Shrum and Doak showed him the door, a number of people attributing the breakup to his fiery temper.

Among the few who tried to heal the rupture was Joe Biden. The reality was, as much of a handful as Caddell could be, the senator just liked the guy and respected his talents.

So tight were they that Biden once stayed as a guest at Caddell’s rented home in Martha’s Vineyard and Biden reciprocated by inviting Caddell to Hawaii.

The writer Jon Ward, national correspondent for Yahoo News, wrote in a remembrance of Caddell that Biden had once referred to the pollster and political consultant as a “godlike figure” and had told Jules Witcover of The Los Angeles Times that it was “hard to know where Pat’s thinking stops and mine begins.”

But that didn’t smooth things over with Biden’s growing presidential campaign staff, who saw Caddell as little more than an explosion waiting to happen.

And they didn’t have long to wait.

On the morning after Biden’s formal entry into the 1988 presidential contest, Caddell confronted a Washington Post reporter who had written about Caddell’s contributions to the candidate’s remarks and went on to mention his connection to the “malaise” speech.

The writer, Paul Taylor, had no way of knowing his piece had incensed Caddell until the two were on an elevator together in a Des Moines, Iowa, hotel.

Caddell continued to berate Taylor all the way to the checkout counter. He then called Biden, who was none too pleased about the incident.

The first sign that it had lasting implications came weeks later, when Biden suggested he not travel with the campaign to the first nationally televised debate of the election cycle in Houston, Texas.

Caddell flew to California, where he had recently begun renting a home, and, according to several accounts, repeatedly tried to reach Biden to sort out his future with the campaign.

Finally, a private dinner was arranged in San Francisco, but nothing was settled. Later that summer, again according to multiple reporters, Biden confided to his senior campaign staff that he didn’t know what to do about his now clearly estranged friend and advisor.

Then, the Biden campaign itself hit a brick wall.

In September 1987, Biden was accused of plagiarizing a speech by British Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock.

Biden’s speech had similar lines about being the first person in his family to attend university.

Though Biden had credited Kinnock with the wording of his remarks on previous occasions, he neglected to do so on two occasions in late August.

The press pounced. Within days, it was reported Biden had also used passages from a 1967 speech by Robert F. Kennedy and a short phrase from John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address.

A few days later, another report said Biden had borrowed some phrases originally uttered by Hubert Humphrey.

Biden tried to explain that politicians often borrow from one another without giving credit, but it was to no avail.

By the end of the month he had withdrawn his candidacy, blaming the “exaggerated shadow” of his past mistakes.

The night before, Caddell had been frantic to speak to Biden.

Excluded from a staff gathering at Biden’s home in Wilmington, Delaware, Caddell called repeatedly from a Washington pay phone.

Finally, Jimmy Biden, the senator’s brother, picked up.

“I want to talk to Joe,” Caddell barked.

Biden, as polite as he could be under the circumstance, said he’d gladly pass along any message Caddell wanted to leave.

“I’ve known Joe for 15 years,” Caddell said. “I don’t need anyone to screen my calls.”

Later, after another round of calls, Caddell got into it with Larry Rasky, the campaign’s spokesman.

“You people have formed a vigilante group to get my candidate out of the race,” he bellowed.

These calls were only the final exchanges of the tirade Caddell had been on since the Kinnock story broke.

He’d worked himself into full battle mode, lashing out at anyone and everyone he thought could possibly be to blame.

He saved his worst for The New York Times reporters who had written the original Kinnock story.

According to campaign workers who witnessed Caddell’s call to the reporter, the pollster and advisor cursed at the reporter repeatedly and banged the receiver against the table.

Caddell later denied this account but Biden is said to have been deeply disturbed when he heard about it and immediately offered to call the reporter and apologize.

A week after he suspended his campaign, Biden met with Caddell in Wilmington.

The conversation was cordial, but Biden’s message was straight to the point — Caddell’s services would no longer be welcomed nor sought by the senator, wherever his future political aspirations might lead.

Later, Biden’s office issued a brief statement. “The senator wants it to be known that he has no animosity toward Pat Caddell, but that he has ended his relationship with him.”

Sees His Party Drifting Away

In Hollywood, the phrase “You’ll never work in this town again” is a cliché of unknown origin. Applied to actors and actresses, it basically means, “you’ll never get cast in another part.”

All over Washington, Caddell’s bust-up with Biden was seen as signaling the same thing, D.C. style.

Caddell himself preferred to explain his apparent breakup with the Democratic party with variations on another employment-related cliché: “You can’t fire me, I quit.”

The party, he’d explain, had drifted from its original vision. It was no longer a party of the people and had become the representatives of the elite, the well-educated, the financial class and interest groups.

Already living on the west coast, Caddell began teaching at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and, with the encouragement of Warren Beatty, another friend dating back to the McGovern campaign days, he got involved in Hollywood.

Together they collaborated on Beatty’s political satire “Bulworth,” and then Caddell struck out on his own as a consultant for such features as “Air Force One” and “In the Line of Fire” and, of course, “The West Wing.”

To many, seeing him tool around Hollywood in his blue 1966 Mustang convertible, Caddell seemed to be living the dream. But politics remained his first love.

In 1992, he dipped his toes back into the water, serving as an informal advisor both to Ross Perot’s independent presidential campaign and former California Gov. Jerry Brown’s primary campaign.

For Caddell, Perot was Jimmy Stewart in “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington” — he was charismatic, spoke to the common man and woman despite his significant wealth and had zero governing experience.

But Perot was also something else — a conservative and according to Caddell, “a genuine patriot.”

The more Perot railed against Washington, the more Caddell loved it.

And it was about this time that the one-time advisor to the likes of McGovern and Carter began saying things like, “my friends are more corrupt than my enemies.”

Soon, he added another ill-humored observation, asserting Washington had been destroyed by “political, economic and media elites.”

Having found a new voice, in no time at all, Caddell found a new venue in which to use it, becoming a regular contributor to Fox News.

In time, he proved to be a withering, relentless critic of both President Bill Clinton and Vice President Al Gore, and when the outcome of the 2000 election was in doubt, he derided the Democrats as a “confederacy of gangsters” intent on seizing power “by whatever means they can.”

At some point, he began including the media in his criticism, calling it “the enemy of the people.”

Candidate Smith Begets Donald Trump

Caddell first met Donald Trump in the 1980s, when the native New Yorker was still just a brash big city developer and was still decades away from his star turn on “The Apprentice.”

“People said he was just a clown,” Caddell later reflected. “But I’ve learned that you should always pay attention to successful ‘clowns.’”

He began to pay even more attention to Trump when the billionaire reached out to him and announced he was considering a run for the White House in 2012.

By then, Caddell had also resumed his search for his elusive “Candidate Smith,” and as it happened, some of his research in this regard had the backing of Robert Mercer, a reclusive hedge fund manager from Long Island, New York, who would eventually become one of Trump’s biggest supporters.

Whatever Mercer’s political affiliations were earlier in his life, by the time he met the disaffected Democrat Caddell, he was a hardcore libertarian who reputedly despised the Republican establishment.

According to Stewart, it was at about this time — 2012 — that Caddell met Steve Bannon for the first time.

Bannon had heard about the pollster’s search for “Candidate Smith” and wanted to learn more. Eventually the two collaborated on a number of projects.

At the time Stewart was one of a handful of people working with Caddell on his research, the others being his longtime friends Scott Miller, Alex Evans and Bob Perkins.

“Pat was a brilliant man who understood public opinion in a deeper way than anyone I have ever known,” she said.

“At this time, Pat was still occasionally appearing on the news, giving speeches and conducting research for other clients, but the work we were doing really revolved around the American electorate’s desire for a candidate like Smith,” she said.

“This is the research that Pat ultimately shared with Trump ahead of the 2016 election that helped him shape some of his populist-leaning messaging.”

Stewart said the same impulse that inspired Caddell to work for Biden played a big role in his being an enthusiastic, informal political advisor for Trump.

“His hope in each case is that they would be the ideal candidate he was searching for — his ‘Candidate Smith,’” she said.

“Pat did a significant amount of polling on the issues that were most appealing to voters and he saw these qualities first in Biden and then in Trump,” Stewart continued.

“Unfortunately, in the end, I don’t think either candidate lived up to this ideal,” she added.

What Caddell’s numbers suggested was that both Democrats and Republicans alike were “ignoring the volcano rumbling beneath them.”

Bannon helped turn Caddell’s findings into a strategy that the vastly outspent and out-organized Trump campaign would use to defeat Hillary Clinton in 2016.

By then Caddell was beginning to have reservations about Trump’s temperament.

“He wasn’t the best Smith,” the pollster said of Trump in the New Yorker in 2015, “but he’s the only Smith.”

That assessment did not diminish Trump’s regard for the South Carolinian.

It had been Caddell, after all, who called Trump on election night and told him his exit polls numbers showed he would win the White House.

It was hours before all the returns were in and Stewart said Trump didn’t believe him.

Caddell stood firm. The trend in his numbers was undeniable.

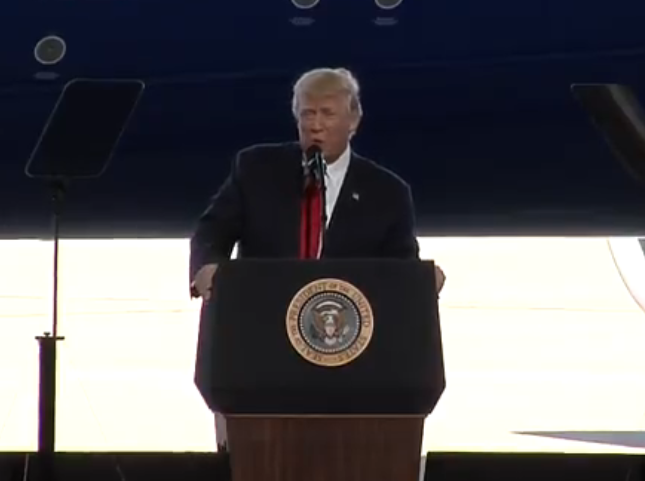

Two years later, in the spring of 2017, the newly-elected Trump toured the massive Boeing passenger jet plant in North Charleston.

Seeing Caddell’s familiar face in the crowd, Trump greeted him warmly and beckoned him over to an area that had been set aside for VIPs and White House staffers traveling with the president.

Once “backstage,” the two spoke privately for several minutes. While neither Caddell nor the White House would reveal what they discussed, that same day Trump unleashed one of the most incendiary tweets of his early presidency.

The news media, he said, “is the enemy of the American people.”

No one who had seen Trump and Caddell together earlier that day thought the post was just another impulsive tweet from the president.

A year later, Caddell, who’d moved to Hanahan, South Carolina, just outside of Charleston, to be closer to his family, stood before a classroom full of students at the College of Charleston.

He’d been a lecturer at the college on and off for the better part of a decade, but this was to be the last time he would ever appear.

His message was, “Sorry.”

“He apologized for what his generation was leaving the current generation,” Stewart said.

The mood Caddell struck was gloomy.

“But he did leave them with the message,” Stewart said. “And it was: ‘You are the only ones who can change this’ … it is up to you to change the system.”

Stewart added that while Caddell enjoyed his time in the classroom, “It was not what occupied most of his time in his last years.

“He was still doing what he loved best — polling. However, his great love was spending time with his three grandchildren,” she said. “That’s what brought him back to South Carolina in the first place.”

Looking back at her friend’s legacy, Stewart said, “Pat figured out how to do polling all on his own in high school. He accurately predicted some state legislative races in Jacksonville as a class project — the local paper even wrote a story about it. He really had a way with data and numbers,” she said.

“I think polls were like a puzzle to him — asking a series of questions that weren’t necessarily directly related could help predict how someone is going to vote,” she said.

“It is interesting that he had a relationship with both Biden and Trump and now here they are! I frequently wonder what Pat would be saying at this moment in time,” she added.

Dan can be reached at [email protected] and at https://twitter.com/DanMcCue