Officials Wary of Aid Fatigue for Ukrainian Refugees

WASHINGTON — As a full year closes in on what Russia calls its special military operation in Ukraine, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that over 7.8 million Ukrainian refugees have fled to neighboring countries and over 65 million people are internally displaced. While officials are vocal in their deliberation for continued outflows of international military support, analysts also wonder whether humanitarian goodwill is sustainable as this conflict continues.

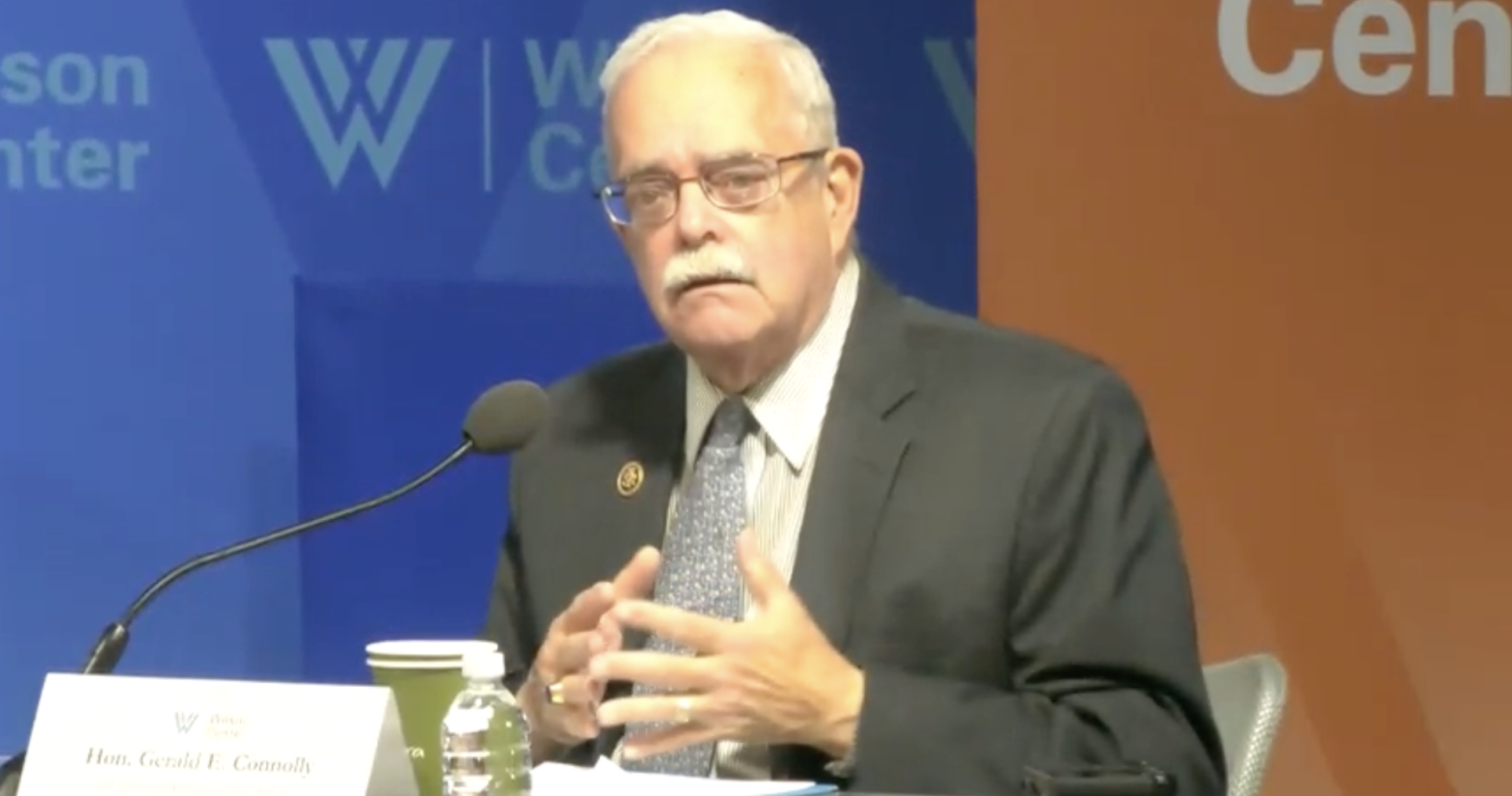

“These are real people who are experiencing extraordinary pain and suffering — in the 21st century — and in Europe,” Rep. Gerry Connolly, D-Va., head of the U.S. delegation to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s Parliamentary Assembly and member of the House of Representatives Congressional Ukraine Caucus, told a gathering hosted by the Refugee and Forced Displacement Initiative at the Wilson Center.

The response of donors from both the private and public sectors has been swift and substantial, but as a growing number of people are forced to flee Ukraine, governments and organizations worry that resources and support could drain.

Calling humanitarian assistance “life saving and critical,” Connolly admitted that as the war drags on and durations of exile are prolonged, some fatigue is “natural,” but “if [a year from now] the war is still going on, we’re — [the U.S. and EU] — going to be unified and solidified.”

Organizations like the European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations are doing a lot of the heavy lifting, providing both humanitarian aid and civil protection to Ukrainian refugees and displaced individuals and families.

“It is a huge operation, and obviously the figures are staggering [in Ukraine], but they are not unique,” Dr. Michael Koehler, acting director general for ECHO, said. “There are a number of crises in the world — not exactly like Ukraine — but that still should not be overlooked.”

In addition to preparing displaced persons for winter, ECHO and other humanitarian organizations provide cash for multipurpose transactions (including basic everyday needs), water and sanitation, education and school bussing, psychological support, and even protection against gender-based violence and murky businesses like organ trading and human trafficking.

Housing also remains a priority.

For its part, the U.S. has welcomed more than 105,000 Ukrainians, according to Ambassador Julieta Valls Noyes, assistant secretary for the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration.

But as the war and displacement continue, the challenge will be to sustain the effort.

“These [aid] instruments were made for short-term impact. Budgeting has not been made for a sustained response,” said Koehler.

UNHCR has coordinated a regional Refugee Response Plan for the Ukraine refugee situation, bringing together 142 partners to support governments’ responses, but donor and host fatigue remain a challenge.

“These are human beings,” Connolly said. “All of the refugees [I saw at the Polish border] were young women with children and older women. There were no men. All of the men … were expected to return to fight. And they did.”

Connolly, “stunned’ by the Polish aid he saw firsthand, held up the Poles as a model for refugee response. He admired how they continue to place huge numbers of refugees between 24 and 48 hours, mostly within private homes, and how even the families of Polish border guards have taken in refugees.

“Imagine the United States’ border guards saying, ‘We’re taking in refugees,’” quipped Connelly.

“The stakes in Ukraine are humanitarian,” he said. “Nothing is forever. … Most Ukrainians are not looking for permanent resettlement. … People always want to go home when it’s safe.”

“Even [at the start of the crisis], people were warning that it was a honeymoon period, that [humanitarian assistance] wouldn’t last,” Noyes said, “and I’m here, and I’m happy to say that the honeymoon continues.”

“As we approach the one-year mark, we have to find ways to prevent host fatigue and to avoid the risk of anti-refugee sentiment that has emerged in other displacement crises.

“The best way to do that is to focus on the true costs of Putin’s war and those that are being borne by the people of Ukraine. The impact of that violence and deprivation will last for a long time.”

Kate can be reached at [email protected]