20 Years Later, Historian Interprets Iraqi Invasion

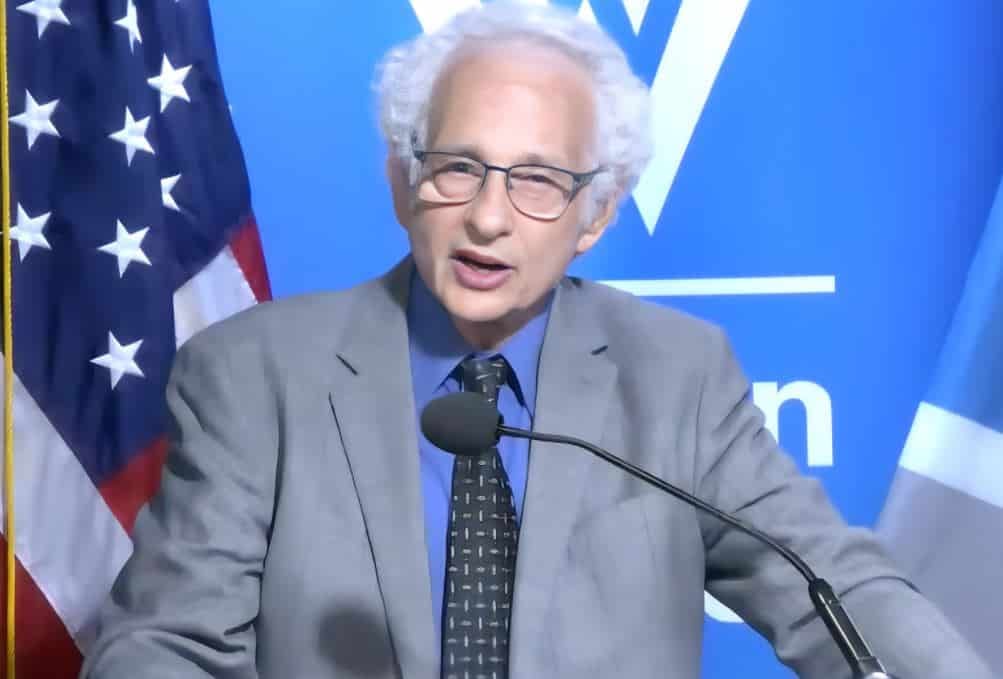

WASHINGTON — American historian Melvyn Leffler discussed his latest book, “Confronting Saddam Hussein,” at the Wilson Center. Twenty years after the start of the Iraq war, the eminent U.S. foreign policy researcher has a new interpretation of former President George W. Bush’s intervention in the country.

It’s largely about fear.

“When fear is mixed with a great sense of power, it’s a dangerous combination,” Leffler told the D.C.-based think tank.

The war, waged on the charge that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, cost countless Iraqi civilian lives and trillions of American dollars. Over 30,000 U.S. military personnel were wounded and some 4,500 were sacrificed in what Leffler said was “probably the most consequential U.S. policy choice since the end of the Cold War.”

“I believe the invasion and occupation turned into a tragedy,” Leffler said, but there would have been, “no invasion without the belief that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction.”

“Overall, my book is designed to capture the decision-making process,” he explained.

Through a unique set of personal interviews with “almost all of the highest officials in the Bush administration other than the president himself,” who Leffler claimed refused to be interviewed, he gained enough first-hand accounts to better illuminate Bush’s reasoning before, during and in the aftermath of America’s invasion of Iraq.

“They were better able to spin than I was to probe,” Leffler quipped, but “as I researched, I saw more complexity, more contingency.”

“First, I argue that President Bush, not Vice President Cheney, not Rumsfeld, not neocons … made all the key decisions regarding Iraq.”

And despite many theories on Bush’s motives, from the greedy — oil — to a noble or “missionary fervor to spread freedom and nurture democracy,” he insists that the Bush administration did not come into office intent on going to war or to enact regime change in Iraq, but rather acted on the mixture of emotion and rationality that shaped decisions at the time.

“His overriding motive was to prevent another attack,” Leffler said.

“Nobody should forget the anxiety that gripped Washington in the aftermath of 9/11,” he reminded.

“I recall vividly that I was here at the Wilson Center the morning of 9/11. We were all bewildered as we saw the replay [of the towers falling in New York] again and again. … I can recall to this day the eerie [emptiness] of the streets of Washington. The foreboding … and then, as anthrax later started circulating in the mail. …

“Analysts struggled, poorly struggled, to do the best they could with suspect informers and inadequate collection methods [regarding terrorist intentions],” he said, and Bush’s overriding sense of responsibility shaped his subsequent behavior.

“Bush did not rush to war. His war planning did not mean war,” Leffler said, examining how Bush tried to implement coercive diplomacy, but the outcome of that diplomacy was contingent on Hussein’s response.

Claiming his purpose in writing this book was not to indict or acquit, Leffler said he still was shocked by flaws in the policy process and policymakers’ unwillingness to reexamine basic assumptions.

The invasion and war were led by “fear, power, hubris, credibility and destruction,” he said. “There are lessons to be learned.”

Kate can be reached at [email protected]