Utilizing HBCUs, Black Churches to Bridge Digital Divide

TUSCALOOSA, Alabama — Implementation of internet and cell phone service was never equitable across the country. Much of the divide is rural versus urban, with population masses driving disparities.

Race also plays a significant factor in the likelihood someone has internet service in their home. As of 2021, 71% of Black people and 65% of Hispanic people have in-home broadband connections versus 80% of white people, according to the Pew Research Center.

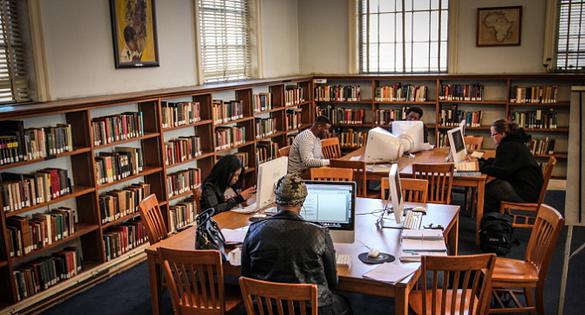

Those disparities were glaring as the COVID-19 pandemic pushed many everyday activities online, from remote work and school to telehealth services. In late 2020, the #BlackTechFutures Research Institute launched at Stillman College, a small historically Black liberal arts college in Tuscaloosa with about 1,000 students, according to HBCU Connect. #BTFRI works with other historically Black colleges and universities, Black churches and communities to address the racial digital divide.

The institute is working to research and help craft policy to address those inequities while also tapping into resources to fund the research to help majority Black cities keep up with the digital economy and build tech business ecosystems. It is also able to connect Black tech entrepreneurs to capital, which has been a large barrier, said Dr. Fallon Wilson, a co-founder of #BTFRI.

“It was coincidentally and fortuitously intentional, knowing we will need data and policy on how to support on-the-ground Black tech ecosystem builders as they addressed the pandemic and many racial tech disparities that would rear their ugly heads, such as the lack of internet access,” Wilson said during a recent interview.

Addressing the ‘Compounding Issues’

Prior to starting the institute with Melissa Brown-Sims, Wilson had seen many one-off programs attempt to increase diversity at specific tech companies or add computer science classes to majority-Black school districts. The programs seemed to “address each issue in a silo,” she said.

“The challenge is, for African American people who live in a racially alienated society, you can’t expect to address one issue at a time because of the compounding issues,” Wilson said.

Instead, the institute’s approach is basically building “an ecosystem solution” that will capture data, resources, policies and programs to help foster the future of Black tech, Wilson said.

Inequities in education and opportunity start young, and they were exacerbated recently when children were participating in remote school from the parking lots of fast-food chains to get Wi-Fi, Wilson explained.

“With the current broadband money, [allocated through federal pandemic aid], there should never be a child sitting in a Taco Bell parking lot not able to access the internet from home again,” she said.

At-home broadband connections create the potential for children to learn coding and other skills for a future in tech careers, Wilson said.

“Tech is the key to these gaps widening or being reduced,” said Isaac McCoy, dean of Stillman’s School of Business and a former senior advisor for business development appointed by President Barack Obama.

McCoy welcomed the creation of the institute at Stillman because he also saw the need to approach systemic racial disparities by lessening the digital divide.

On the Ground Work

The institute is also deep in its work with leaders in four cities with large Black populations — Birmingham, Alabama, Nashville and Memphis, Tennessee, and Houston, Texas — to create Black tech ecosystems. To create those systems they are working to strengthen STEM education in public schools and build a tech workforce where companies retain Black talent, Wilson said.

“In order to build a future for Black people [in tech] we have to understand these cities,” she said.

Ongoing research with other HBCUs will tackle topics including tracking federal pandemic infrastructure aid that can be used to build STEM programs in schools and expand broadband infrastructure.

“Those billions of dollars could end the digital divide as we know it,” Wilson said, emphasizing the word “could.”

And there’s outreach working with Black churches and other religious organizations because they already have trust built within Black communities, Wilson said.

Those working with the institute are also bringing their work front and center with its second Black Tech Policy Week, where during the last week of April they will host virtual panels to discuss topics such as public interest technology, broadband infrastructure dollars, Black digital entrepreneurship and municipal Black tech ecosystems.

Everything is free and will be live-streamed, which is important to make it more accessible, Wilson said. It’s sponsored by a variety of tech organizations, including the Aspen Tech Policy Hub.

“As a tech policy organization, we know that the field often lacks diverse voices — especially Black voices — and we’re excited to see an initiative challenging that status quo,” wrote Meha Ahluwalia, the project manager at the Aspen Tech Policy Hub, in a statement.

The variety of topics will hopefully appeal to a wide range of people, Wilson said.

“We need thought leaders across all racial backgrounds and not just at tech companies,” Wilson said, explaining that people from all sectors — government, education, health care and private business — all need to be involved.

Highlighting her enthusiasm for #BTFRI’s home in Tuscaloosa, Wilson said, “Stillman is a place to incubate Black genius for Black futures.”

Madeline can be reached at [email protected]