Storytelling Increases Oxytocin in Children Admitted to ICU

A study published this week indicates that just one session of storytelling can increase oxytocin, reduce cortisol and pain, and promote positive emotional shifts in children admitted into an intensive care unit.

“As a storyteller myself I decided to investigate if all changes we are seeing in children when we are telling stories were possible to be scientifically measured,” said Guilherme Brockington from the Federal University of ABC in Brazil.

The researchers from the D’Or Institute for Research and Education and the Federal University of ABC hypothesized that storytelling is capable of inducing children to feel transported to another possible world, one that is distant and different from the threatening environment of the ICU.

As a result, the adverse physiological and psychological reactions experienced during a child’s ICU stay would be temporarily reduced.

To test the hypothesis, researchers recruited 81 children aged 4-11 years old who were hospitalized in ICUs. Through randomization they placed the children into two intervention groups with 41 children in a storytelling group, and 40 children in a riddle group. The children all had similar clinical conditions, with respiratory problems of asthma, bronchitis, pneumonia being the most common.

In the story intervention group, children were given an option to choose among eight light-hearted or amusing stories typically found in children’s literature, such as Little Red Riding Hood.

“We avoided using any very popular books or stories that were widely circulated on mass media because this might have … influenced the child’s appreciation of the story. We also used children’s books that weren’t emotionally loaded to be sure that effects we found were from the narrative transportation per se and not due to an emotional manipulation,” said Brockington.

Children were given the option of changing the story or asking for a particular one to be retold by one of the six recruited storytellers, who had more than 10 years of experience in hospitals reading to children for 25 to 30 minutes.

In the riddle group, which lacked the narrative immersion provided by the story group, the storyteller would play a riddle game with the children for 25 to 30 minutes and then ask the children to solve questions like, “What opens all the doors without ever going in or out of them?”

“The control condition included elements of both playfulness, language and social interaction, but did not include the immersion aspect created by storytelling,” said Brockington.

A saliva sample, standardized pain scale questionnaire, and free-association word quiz were all completed by children immediately before and after the intervention to assess how much pain was felt before and after.

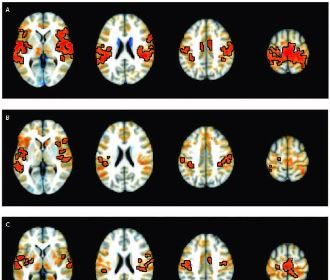

Using saliva sampling, researchers found that storytelling increased salivary oxytocin levels, and reduced salivary cortisol levels, and pain scores in comparison to the riddle intervention

Researchers also found that the human connection and meaning-making of a story allows a child to reshape their linguistic associations formed about hospital environments.

This study demonstrates a direct link between oxytocin and empathy, emotional processing, and, by extension, a reduction in mood disorders, the lessening of fear responses, and the capacity to infer other people’s emotional states.

“Although the research has been developed in a hospital, the ICU environment may have most similarities with a reality that most of children are living nowadays due to the COVID-19 pandemic: the social distancing, that keeps them far from their friends and dear relatives, the levels of stress and tension caused by an illness, the boredom of being in the same place for several months. That way, storytelling by parents, relatives and friends may be a simple and effective way to improve the wellbeing of a child and is accessible to all families,” said Brockington.

These important clinical implications affirm storytelling as a low-cost and humanized intervention that can improve the well-being of hospitalized children.

“We hope that this study helps increase the awareness for more humanized clinical practice. We certainly believe adding simple and cost-effective interventions such as storytelling can help children to feel less stressed, which can help with recovery,” said Brockington.