Recalling the Pentagon Papers Case, 50 Years On (Part Three)

(This is the third part of a four-part series. The first and second installments can be read here and here.)

White House Makes Its Move

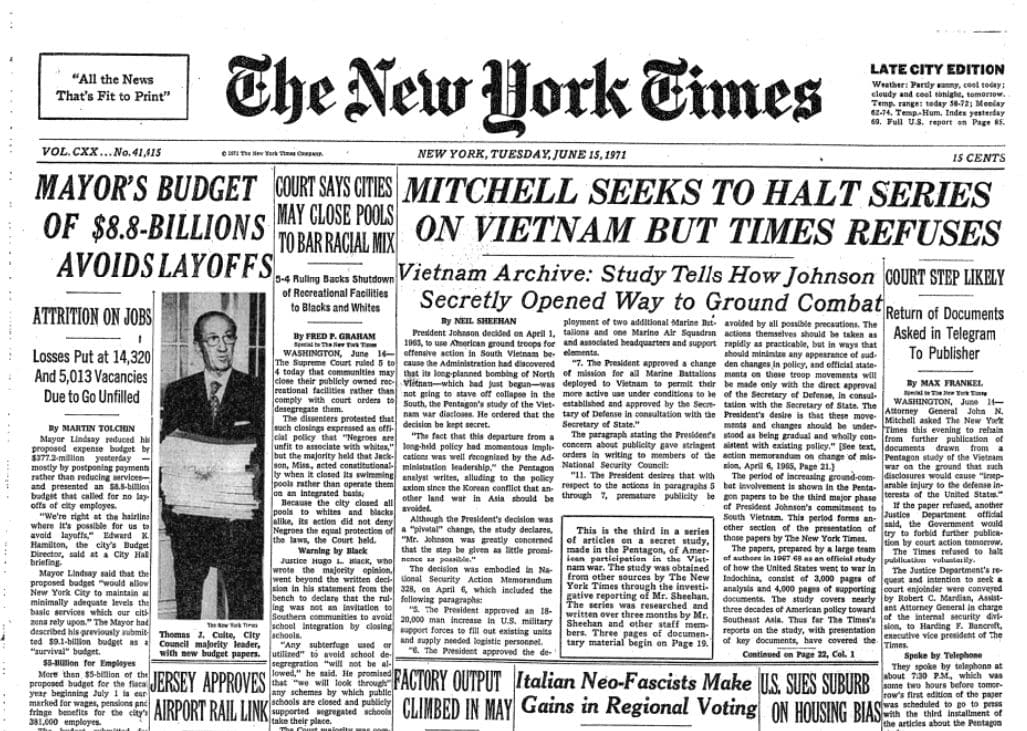

Ultimately, the decision to seek prior restraint — an injunction prohibiting The Times from publishing future articles — was made by Robert Mardian, the assistant attorney general for Internal Security Affairs.

At the time, of course, Mardian had no idea what was in the documents, but in the interest of erring on the side of caution, he decided the most prudent thing to do would be to give The Times a chance to stop publishing voluntarily. If that failed, then the White House would have no choice but to go to court to stop it.

The Telex from the attorney general set off a firestorm at The Times, with editors and executives splitting into factions, for and against publishing. Finally, Abe Rosenthal insisted on calling Arthur Sulzberger in London — it was 2 a.m. there by this time — and James Goodale urged him to allow publication.

Sulzberger wasted no time in coming to a decision. The New York Times would not voluntarily submit to censorship. The publisher ordered the printing to continue. In the meantime, the newspaper issued a statement announcing it would “respectfully decline” the government’s request to stop publication of the series

That Tuesday morning, the third article in the Pentagon series ran on the front page. Above it, however, was another, though related story: “Mitchell Seeks to Halt Series on Vietnam but Times Refuses.”

A bare-knuckled legal battle was now unavoidable, but Goodale was in a fix — Lord, Day and Lord declined to take the case.

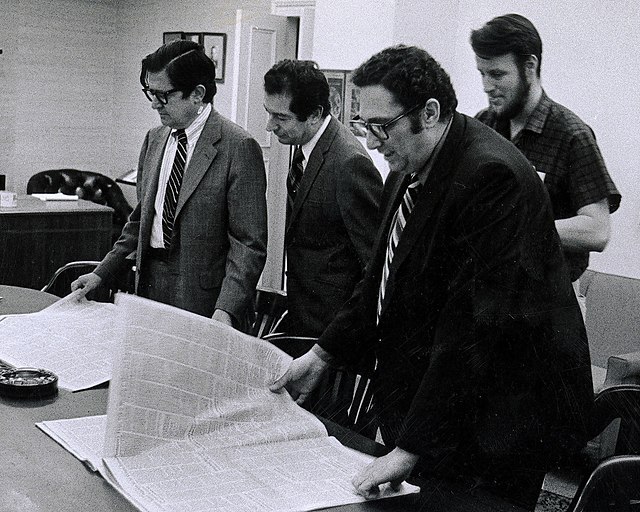

Goodale’s next step was to call a Yale Law professor named Alexander Bickel, with whom he’d already discussed the controversy surrounding the papers. Unable to immediately locate Bickel, he then called Floyd Abrams, an associate of Bickel’s and a partner at the New York firm of Cahill Gordon.

By dawn Tuesday, Bickel had been located and he and Abrams were hard at work on their arguments for the next morning’s now certain court appearance.

Case Handed to Novice Judge

The Pentagon Papers case was assigned by lot to U.S. District Judge Murray Gurfein, a new Nixon appointee, who had been sworn in only a week before.

At 63, this case was his first as a judge, and by the time he took his seat behind the bench in the U.S. Courthouse in New York’s Foley Square, the courtroom was packed with spectators.

Arguing for the government was U.S. Attorney Michael D. Hess. The gist of the government’s arguments was The Times had violated a statute that makes it a crime for persons having “unauthorized possession” of government documents to disclose their contents under circumstances that “could be used to the injury of the United States or to the advantage of any foreign nation.”

Hess claimed “serious injuries are being inflicted on our foreign relations, to the benefit of other nations opposed to our form of government.”

With the government facing the prospect of “irreparable injury” in its international relations, Hess said the Times should be required to suffer at least a “slight delay” in its publication schedule until the case could be heard in its entirety.

At 46, Bickel was not only a renowned legal scholar — he was already being mentioned as a possible Supreme Court nominee.

“Tanned and dapper” according to news accounts of the hearing, Bickel replied to Hess on behalf of The Times by arguing that this was a “classic case of censorship” that was forbidden by the First Amendment’s guarantee of a free press.

He also insisted the statute being evoked by the government was an anti-espionage law that had never been intended by Congress to be used against the press.

To bar a newspaper from publishing certain matter “for the first time in the history of the Republic,” would set an unfortunate precedent, he said.

“A newspaper exists to publish, not to submit its publishing schedule to the United States government.”

Judge Gurfein granted the government’s request for a temporary restraining order — the first time in U.S. history that a court, on national security grounds, had stopped a newspaper in advance from publishing a specific article.

Outraged, The Washington Post soon began preparing to run its own articles based on documents Ellsberg had given its reporters. As at The Times, however, the decision to move forward didn’t come easy. A fierce battle erupted between the newsroom and the paper’s reluctant attorneys.

Finally, publisher Katherine Graham sided with the newsroom, and the Post joined The Times on the front lines of the censorship battle.

Several other newspapers across the country soon followed suit.

The court proceedings that followed had a frantic rapid-fire air to them, and as the hearings, most of them closed to the public, went on, the government’s case began to crumble as it became ever clearer that there was no immediate military danger that could be caused by publishing the contents of a three-year-old report.

Indeed, much of the information the White House claimed it was so incensed about was already in the public domain, having been revealed at Congressional hearings or reported by the press.

In fact, Vice Adm. Francis J. Blouin, deputy chief of Naval Operations for Plans and Policy admitted his testimony was based not on fear of any immediate military peril but on the more general ground that “there is an awful lot of stuff in [the Pentagon study] that I would just prefer to see sleep a while longer.”

On Saturday, June 19, 1971, Judge Gurfein decided the case in favor of the Times, prompting the government’s attorneys to rush upstairs in the same courthouse to obtain an appellate court order continuing the ban on publication.

The following Wednesday, the appeals court went a step further and ordered Gurfein to conduct additional hearings so the government could fully air its case.

It was at this point that both The Times and The Washington Post filed papers seeking emergency review of the case by the U.S. Supreme Court.

The reaction to all this on Capitol Hill was swift. Upon reading the first of The Times’ Pentagon Papers stories, Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield announced that the Senate Foreign Relations subcommittee on the Far East would hold public hearings on how the United States had become involved in the Vietnam War.

The Montana Democrat told reporters that he had been “surprised, shocked and astounded” by the revelations in the documents … largely because it was now apparent the Johnson administration had made the decision to enlarge the war in Vietnam without informing Congress.

Sen. Henry Jackson, of Washington, vowed to press for a joint hearing by the Senate Armed Services Committee and the Foreign Relations Committee.

(The story of the Pentagon Papers concludes with the Supreme Court handing down a landmark decision in favor of a free press.)