American Genius: The Story of the Journalist Nellie Bly

In observance of Women’s History Month, The Well News recalls the life and career of a great journalist and adventurer.

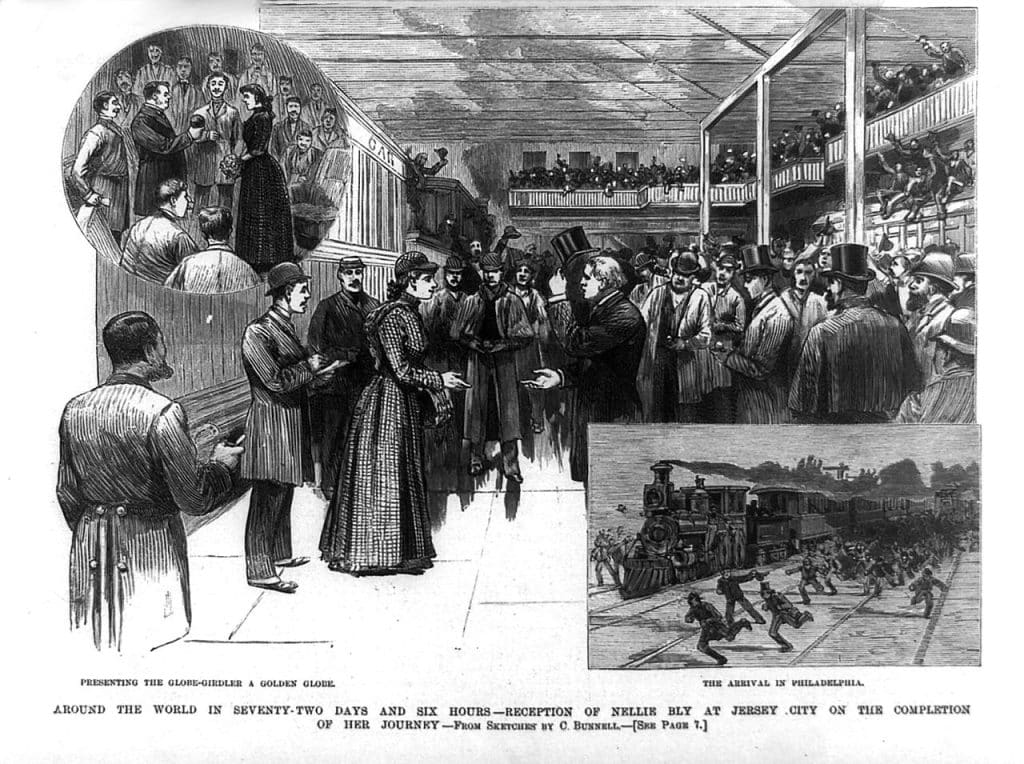

The crowd at the Jersey City Railroad terminal had been building for hours by the time the train from Pittsburgh pulled into the station at 3:51 p.m. on Jan. 25, 1890.

Though no one could ever say for sure, their numbers, spilling out into the surrounding streets, were surely in the low thousands when the slim, smiling young woman stepped off one of the train’s passenger cars and waved her Ghillie cap at the throng.

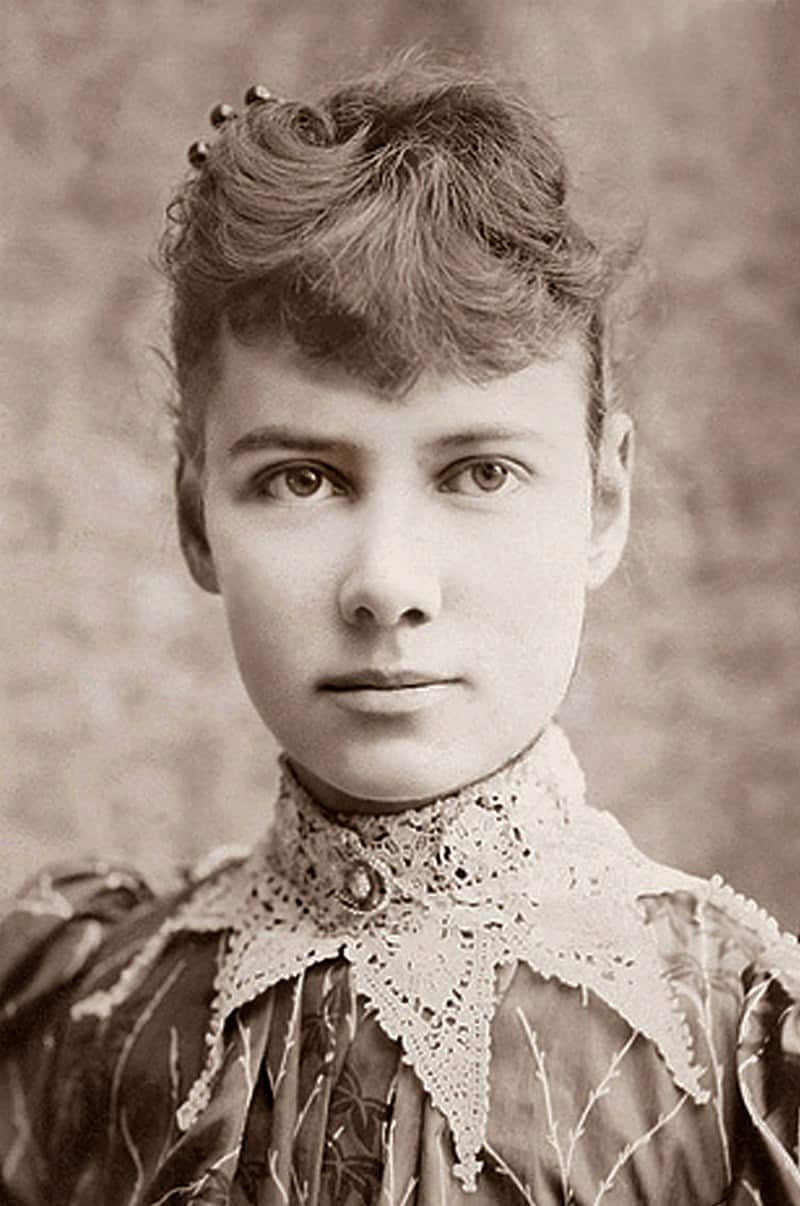

Those that could actually see the five-foot four-inch tall journalist, whose dark brown hair was fastened back with a gold pin and came forward in short, slightly curled bangs, went wild, their cheers sweeping through the building and causing even the most distant to strain to take a look.

At 22, Nellie Bly had broken the fictional record of the author Jules Verne’s Phileas Fogg by circumnavigating the globe in less than 80 days.

She was in that moment America’s sweetheart, and on that cold and blustery afternoon, the adoration of all those who’d been reading of her global exploits for the previous two-and-a-half months came down on her like a great crashing wave.

“Now there was no holding them back,” wrote the author Mignon Rittenhouse, who decades later would write “The Amazing Nellie Bly” about her exploits. “They surged forward, eager to touch the miracle girl.”

Among those most aggressively heading in her direction was Jersey City, New Jersey, Mayor Orestes Cleveland, a long time pol and former congressman who knew a thing or two about associating himself with someone else’s success.

Shoving his way through the increasingly hysterical mob, it was only when he reached Bly’s side that he realized the bouquet he had brought for her had been utterly destroyed.

Undeterred by the mayhem, Cleveland tried to make himself heard.

“The American girl can no longer be misunderstood,” he cried out, according to Rittenhouse’s telling. “She will be recognized as pushing, determined, independent, able to take care of herself wherever she may go.

“You have added another spark to the great beacon light of American history that is leading the people of other nations in the grand march of civilization and progress,” he said.

Bly’s attempted response was cut off by police officers at the scene who admitted to the mayor that they’d lost all control of the situation.

According to one newspaper account, the officers then circled both the hero reporter and the mayor and used their night sticks to “beat their way” to the carriage that would take Bly to the ferry waiting to take her to New York.

Because she’d begun her 29,100-mile journey from Jersey City, 72 days, 6 hours, and 11 minutes earlier, she had already accomplished her goal of going completely around the world.

The trip across the Hudson River to New York City, therefore, was just a bit of icing, mixed with a little business.

Still, the hero’s welcome continued.

Tug boats and steamships blew their whistles as she passed, and cannons roared from Battery Park and Fort Greene in Brooklyn.

Arriving at the Cortlandt Street landing, another large crowd greeted her as she was helped into the carriage that would take her to the New York World newspaper building on Park Row.

Such was the commotion that Bly stood up in the carriage and bowed, to the right and to the left, tipping her cap to her avid fans.

One competing paper, unable to stomach the triumph of a rival, reported in its next edition that the scene was “awful” with “men and women and children being pushed down and trod upon.”

Once inside the New York World’s offices, Bly was escorted to the managers room where a short reception was held in her honor, prior to a formal dinner at the Astor House.

In between, she made her way to the windows of the World’s editorial department and waved, to the sound of cheers, at the New Yorkers assembled to welcome her home.

“I feel,” she confessed to a fellow reporter, “like a successful presidential candidate.”

Born into Comfort, Buffeted by Hard Times

She was born Elizabeth Jane Cochran on May 4, 1864, in a town that bore her family’s name a few miles outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. By the time she reached her mid-teens she was a singular self-creation, becoming a newspaper star in an era when the front page was entirely dominated by men.

But it wasn’t just her gender that set her apart. From the first, Bly wrote in a participatory style that placed her at the center of the action, whether she was covering hard news or writing a feature. In that way, her approach, which also relied heavily on dialogue, anticipated the New Journalism of the 1960s and 70s.

Critics and detractors, of which she had her share, attempted to dismiss her style as shallow and lacking in gravitas, citing stories like the one headlined “Nellie Bly Asks Senator David B. Hill Some Questions No Man Would Dare Response.”

The lede of the story in that followed was:

“I asked Senator David B. Hill if he was ever in love.

“He glanced at me quickly, his eyes twinkled for a moment, and then he hid himself behind a newspaper and said something about the question being a delicate one.

“And that is all he would say on the subject.

“It is my opinion that he was in love once, very desperate, and that something went wrong.”

But draw a throughline backwards from Hunter S. Thompson, Joan Didion, George Plimpton, Tom Wolfe and Jimmy Breslin, and you inevitably wind up at Bly, at her best.

What is known about her early life is contradictory. Biographers and even some of her contemporaries lean heavily on words like “spunk” and “vibrant” and “energetic” in describing the child who had to fight for attention in a home that included 13 brothers and sisters.

And yet, by the time she was six years old, her father, a judge, had died and complications related to his will left the family impoverished. And even though Elizabeth Jane’s mother quickly remarried — as much to provide some family stability as for anything else — the new man of the house soon proved to be a violent drunk.

The downward spiral in the marriage ended in a divorce trial at which the 14-year-old Elizabeth Jane was forced to testify about her stepfather’s mistreatment of her mother.

“My stepfather has been generally drunk since he married my mother, and when drunk he is very cross,” she said.

“He is cross sober, too,” she added.

Through it all, it has been written, Elizabeth Jane’s mother encouraged her to dress in bright colors and to continue to be as witty and vivacious as she had been in the past. But already, it’s clear, her mother’s experiences showed that marriage — then considered the ultimate goal for a woman — did not always make for happiness or even longlasting security.

Hoping to assure her own independence, Elizabeth Jane took a stab at becoming a teacher, but was forced to quit her studies after only one semester when her mother and siblings again fell on hard times.

The family soon moved to Pittsburgh and felt lucky when they were able to scrape up enough to open a boarding house. It was while carrying out some duty or another there that Elizabeth Jane came across a copy of the Pittsburgh Dispatch newspaper and the column that would quite literally change her life.

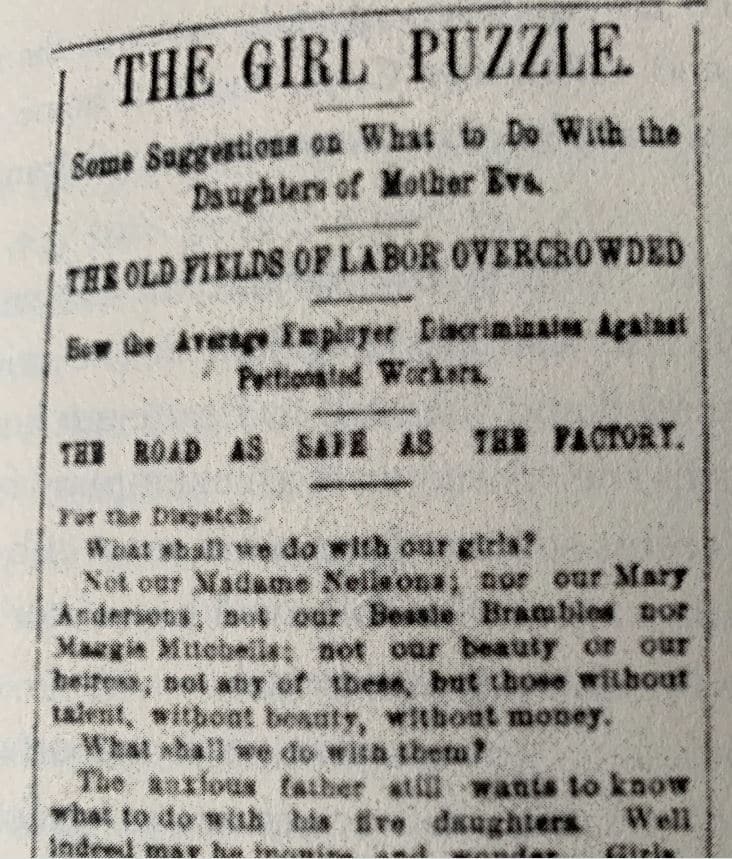

It was written by a columnist named Erasmus Wilson and ran alongside an anonymous letter to the editor from an anxious father who was wondering what to do with his five unmarried daughters.

The headline of Wilson’s response was “What Girls Are Good For,” and in it he asserted women were good for nothing but staying at home and giving birth. Wilson, who used the pseudonym “the Quiet Observer” went on to label women who worked for a living a monstrosity and asserted the growing pressure to grant women more rights in society was surely a sign standards were slipping.

Taking this all in at the boarding house, Elizabeth Jane was livid. One can even imagine her pacing until she finally decided she couldn’t let it pass.

Instead, she drafted a column in response and rushed it into the mail. She signed her first piece, “Lonely Orphan Girl.”

A few days later, Dispatch Managing Editor George Madden came upon the column and was immediately drawn to the high caliber of the writing and unrestrained ferocity of the writer. There was only one problem. He had no way of knowing who the “Lonely Orphan Girl” was.

To find out, he published an ad on the next day’s front page, inviting the “Orphan Girl” to meet him at his office. The next day, Elizabeth Jane showed up at his door.

Madden had a proposal for her. Would she, he asked, be interested in writing a regular column on a trial basis for $5 a week?

She would, she said. And within a day or two came up with the name she’d be known by for the rest of her life: Nellie Bly was born.

Arrival in New York

Like almost all the women who had worked at newspapers before and after this time Nellie Bly was effectively put on the “women’s issues” beat, but instead of recipes and homemaking and society gossip, she diligently devoted herself to writing about the social wrongs that were meted out to those of her gender.

For one exposé, Bly went undercover as a factory worker and wrote of the poor conditions the women were forced to endure for the pocket change they were paid. In another of her pieces, many of which can be found in the newspaper collection of the Library of Congress, she expounded on the unfair treatment women like her mother received in divorce proceedings.

Writing from such a novel perspective, Bly was an almost instant hit with readers. She wasn’t so popular, however, with advertisers, some of whom had been the target of her investigations and others that simply didn’t want to be associated with controversy.

When the advertisers began pulling their ads from the Dispatch, the paper had no choice but to let her go.

Bly next turned to New York, where, after four stark months of unemployment, she was offered a tryout by the Joseph Pulitzer-run New York World.

In New York she wrangled a job on The New York World newspaper, where her first sensational coup was to get herself consigned to the wards of the insane on Blackwell’s Island.

Her beat would essentially be the same as the one she created for herself in Pittsburgh, and one of her first assignments in New York would not only make her initial fame, but it would cast her in the dual role of journalist and reformer.

In the late 19th century, those who were mentally ill were simply locked up and isolated from society, often in horrific conditions. Women who were diagnosed with mental illness were the most unfortunate of all.

In New York in the 1880s and 1890s these women were sent to what was uncharitably referred to as the “lunatic asylum” on Blackwell’s Island, known today as Roosevelt’s Island.

When it opened in 1839, the asylum on Blackwell’s Island was seen as an advance, being New York’s first publicly funded mental hospital and the first municipal mental hospital in the United States.

But by Bly’s day, horror stories about the treatment of the patients at the asylum were commonplace.

During a meeting with her editors, Bly explained how she planned to get into the asylum, noting she’d been practicing facial expressions to make herself seem as unhinged as possible.

Her editors kept their instructions simple: she was to write up things as she found them, good or bad, to give praise and blame as she saw fit, and finally, to tell the truth of her experiences all the time.

The only thing everyone overlooked was how they would eventually get her out.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

On the night of her institutionalization, Bly went home and made a great show of being afraid of everything she encountered. Then she spent hours staring at a wall and saying nothing.

Eventually, the police were called and Bly was hustled off to Bellevue Hospital for an assessment. At Bellevue doctors recommended that she immediately be taken to Blackwell Island.

Once there, Bly observed that most of the patients she encountered did not seem to have all that much wrong with them. Armed with this observation, Bly decided to drop her act and quickly made a discovery: “The more sanely I talked and acted, the crazier I was thought to be.”

For 10 days she was subjected to twice daily ice baths, to an early version of waterboarding, to eating rotten meat accompanied by dirty water and to living in conditions that included frequent exposure to human waste and rats.

When she wasn’t in her room, Bly said, she was forced to sit on a hard bench for hours on end and not talk to anyone or read.

In one of the columns she later wrote of the institution, Bly wondered “What, exceptng torture, would produce insanity quicker than this treatment?”

Finally, fearing for its reporter’s well-being, the New York World contacted the institution and revealed a reporter was within its midst. The first of her columns on her experience appeared in the newspaper two weeks later.

The city’s reading public was mortified, as was the nation’s, when the pieces were picked up and carried in newspapers far and wide. So too was the hastily convened grand jury that ordered the asylum to clean up its act and implement a series of much-needed reforms.

New York City itself added a million dollars to the budget of what was then called the Departments of Charities and Corrections to ensure patients were kept in more humane conditions and that kinder, safer treatments were being given.

Such was the commotion over her work that the mistreatment of patients at the asylum became the subject of her first book, “Ten Days in a Mad-House,” which was published in 1887.

And Nellie Bly, for the first time, became a national celebrity, praised both for her bravery and for shining a spotlight on societal ills.

More undercover work followed, including additional exposes on the squalid conditions in sweatshops, and the cruelty of the illegal trade in newborn babies, but she soon began to think seriously of an entirely different kind of story, one that would take her penchant for participatory journalism to new heights and great lengths.

Around the World

The French writer Jules Verne first published his book “Around the World in 80 Days” in his native France in 1872, and it became a worldwide bestseller in translation.

In the story, Phileas Fogg of London and his newly employed French valet Passepartout attempt to circumnavigate the world in 80 days on a wager of £20,000 set by Fogg’s friends at the stuffy, gentleman’s Reform Club.

The book featured marvelous backdrops, exotic doings, including traveling by elephant and a daredevil train run over a collapsing bridge.

All this, plus a dramatic twist at the end made it one of Verne’s most revered books.

Like everyone else who read it, Bly became enamored with the romance of “80 Days,” but where others closed the back cover satisfied in a book well read, she saw it as something else — a story she could actually pursue.

By all accounts, Bly’s editors were cool to the idea. First, they wondered, would anybody really be interested in reading about somebody breaking an imaginary record? Then there was the issue of Bly’s safety. It was bad enough when she’d been in an asylum across town, how would it be if she got into trouble half-way around the world?

Finally, there was the question, raised delicately, of whether she thought she could actually do it?

But Joseph Pulitzer had other factors he was considering, among them that the World was experiencing a readership slump. Even if she didn’t ultimately beat the record, Bly’s regular dispatches from far-flung locales could be just what his paper needed.

And then, all concerned got a gift.

Hearing of the World’s plan to send Nellie Bly around the world, John Brisben Walker, publisher of Cosmopolitan magazine, decided to make a race of the event, announcing he would send his literary editor, 28-year-old Elizabeth Bisland, around the world in the opposite direction.

Both women would leave on the same date, Nov. 14, 1889, with Bly heading east, Bisland west.

By making the respective journey’s a contest, Walker assured that the public would keenly follow the progress of both woman, but Pulitzer and the World were in the best position to capitalize on it because the newspaper came out every day, giving it more opportunities to play up its competitor — it virtually ignored Bisland — and to stoke interest in a contest for readers on the precise time Bly would finish her trek.

Cosmopolitan, meanwhile, was a much different magazine than the Cosmopolitan of today, often described as genteel. At the time of the race, Walker had only just acquired the monthly, which had a total circulation of 25,000.

The two women involved were also a study in contrast. Bly, already having a well-earned reputation as an ambitious and hard-driving reporter, didn’t worry too much about the finer things as she prepared for the voyage.

She would carry nothing more than a small hand satchel, keeping £500 in Bank of England notes in a purse hung around her neck.

The satchel, published reports said, contained nothing more than one dressing gown and a few other items, plus her railroad and steamer tickets for the entire journey. As for her daily outer garments, she planned to wear one outfit for the duration, washing it out at night.

Bisland, by contrast, was born a Southern aristocrat, and preferred the finer things including novels to read during the long stretches when nothing but expanses of water and fields were sure to be outside her window.

On the morning of departure, Bly traveled by ferry to Jersey City and boarded the steamship Augusta Victoria for Southampton, England. From there she was scheduled to travel to London, Calais, Paris, Turin and Brindisi, where she would take a steamship for Hong Kong and Yokohama and another for San Francisco, before boarding a series of trains for the last length home.

Bisland, heading westward, would be taking a route about the same as Bly’s, only in reverse.

Initially, Bisland appeared to have the upper hand. After leaving the dock at six seconds past 9:40 a.m., Bly was forced to endure a stormy voyage across the Atlantic and got seasick and couldn’t hold down any food. The only thing that made her feel better was sleeping.

And at one point in the voyage she slept for so long that the ship’s crew feared she’d died in her cabin.

Things got unexpectedly worse when the Augusta Victoria arrived in Southampton and Bly was told she’d missed the day’s last regular passenger train to London.

After having felt so terrible, the news must have seemed like a crushing blow. But a few minutes later, she learned of a change in plans. The Augusta Victoria had arrived in Great Britain loaded with mail from the U.S. and the English postal authorities wanted it to reach London in time for the morning mail delivery.

If she didn’t mind riding in the mail trail, she was welcome to come aboard. Bly arrived in London that night and immediately made her way to the New York World offices there.

She let everyone know phase one of the journey was complete and sent her first dispatch. She didn’t ask about Bisland.

An Interview with Jules Verne

Of course, it may well have been that she was already looking forward to her next stop, meeting Jules Verne himself for an interview to be conducted at his home in Amiens, France.

Bly rose early the next morning and boarded the tidal train via Folkestone and Bologne for Amiens.

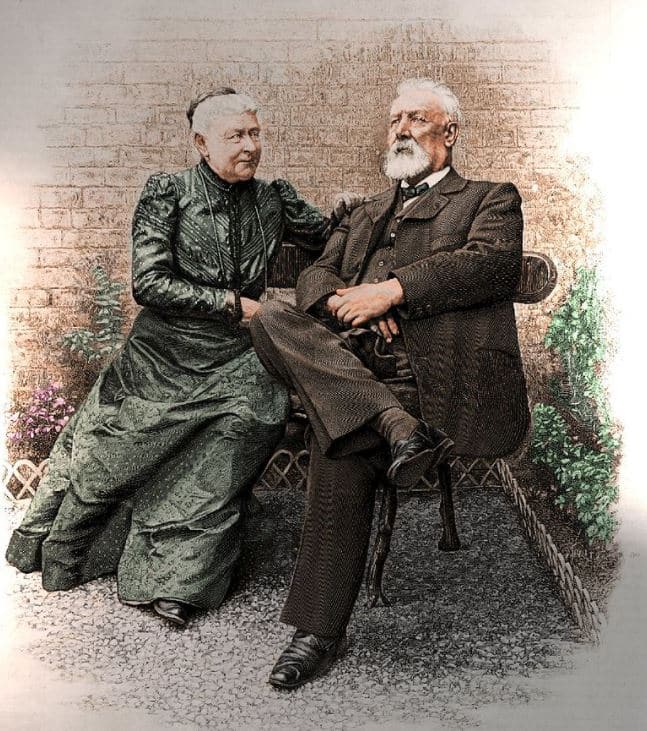

When Bly arrived, at about 4 o’clock in the afternoon, she could see the famous author and his wife, pacing back and forth on the platform of the Amiens railway station.

Verne admitted to the New York World correspondent waiting with them that “I feel as much interest in the success of the enterprise as I did when I was following Phileas Fogg and his friends around the world in my study.”

As Bly stepped off the train, both Vernes were overcome with excitement, with Mrs. Verne, the former Honorine Anne Hébée du Fraysne de Viane declaring in her broken English, “Mon Dieu, what a child. Is it possible that the lady is going all that long way alone?”

It took the party about 20 minutes to get to Verne residence and almost as soon as they entered the gray-haired author said, “The first thing I want to know is what route you are going to follow.”

“The New York, Southampton, Calais, Brindisi, Colombo, Hong Kong, Yokohama, San Francisco, New York route,” Bly said, surprised she could recite the entire route in French without a mistake.

“Why do you not land at Bombay and travel across India to Calcutta like Phileas Fogg?”

“No, it would not be of any use,” Bly said, going on to explain she would have to wait a day or two longer in Yokohama, “and there would be no advantage in that.”

“Besides, you know, people who cross India in these expeditions,” referring to one of the incidents in Jules Verne’s novel, “come back married, and that is just what I do not want to do.”

Both Vernes laughed at this, and the author marveled, “It really is not to be believed that that little girl is going all alone around the world; why, she looks like a mere child.”

“Yes, but she is just built for work of that sort,” his wife said. “She is trim, energetic and strong. I believe, Jules, that she will make your heroes look foolish; she will beat your record.”

Verne shook his head, and laughed.

“I would not like to risk my money,” he said.

Mrs. Verne then suggested that if she told her friends the young adventurer before them was a journalist, she’d never be believed.

“Ah” her husband said. “But then your friends don’t know what American newspapers are, and the New York World seems to be the most American of them all.”

Turning to Bly he added, “Your success, mademoiselle, should be a great feather in the cap of the paper that has the advantage of possessing your services. The idea is a splendid one and shows the greatest enterprise.

“I think that the journey is one of real interest from a scientific point of view also because until now nobody has beaten the record of my imaginary Phileas Fogg.”

Verne went on to suggest Bly’s trip might have broader repercussions.

“It should stir the Russian government to begin upon the Trans-Siberian Railway,” he said. “When that is finished, mademoiselle, you will be able to beat the record, which I am convinced you are about to make yourself, and get around the world in 75 days.”

“Have you ever been to America?” Bly asked.

“Yes, but only 12 days,” Verne said. “However, now that I have seen you, Miss Bly, I only wish all the more to be well enough some day to visit again because it seems that since I was there your extraordinary nation has grown even more extraordinary.

“I am sure that there is no other country in the world where you could find a young woman who would venture to do what you are doing and certainly none where a newspaper would shoulder the cost of backing her in such an experiment for its scientific value.”

Bly eyed the Louis Quinze clock on the opposite wall of the room and saw it was almost time for her to leave. She asked if she could see his writing room before she continued on her journey.

“With the greatest of pleasure,” Verne replied.

With that, he took up a lamp and led the way through the hall to a turret staircase, which they climbed for three flights.

At the top of that stairs, Bly saw Verne’s room, which served as a study and bedroom in one. Upon a small table under one of the two large windows in the room were copies of the author’s books, all tidily arranged, his writing materials and paper.

Also on the table was the manuscript of his latest novel.

Bly marveled at Verne’s excellent penmanship and the extraordinary number of corrections on the page.

“Yes,” he said. “You see, I correct a great deal. That is a page of manuscript from the 10th copy of a novel. Often, I entirely rewrite a whole work. … I don’t believe in dashing off things. One can’t attain anything good in the world without labor and fatigue.

“I think you will know something of the same feeling, mademoiselle before you get to the end of the journey you are undertaking,” he said.

While they spoke, Mrs. Verne set out some wine and cake in the drawing room downstairs.

Though Verne had long ago stopped drinking for his health, he said, “I must make an exception on this occasion and drink a glass on the health of the young lady and wish success to her trip.”

The Journey Home

Bly ventured back to Calais to catch the Brindisi mail train, at the time, one of the most important and famous trains in the world because it served as a passenger and cargo connection between London and the British colonies in India.

She then boarded another steamer ship, the Victor of the Peninsula and Oriental line, crossing the Mediterranean and sailing through the Suez Canal into the Arabian Sea before spending two days on the Island of Ceylon, now known as Sri Lanka.

All the while, the New York World’s readership was kept updated by the dispatches she sent back to the United States by telegraph. Most of her reports were filled with adventure, glamor and peril, with an occassional bout of homesickness helping to humanize her adventure and make her the toast of five continents.

When Bly’s dispatches failed to arrive —and there were occasions when for one reason or another, she’d disappear for days on end — rewrite men filled the gaps with gripping tales made up for reader consumption.

Other newspapers, including the Washington Post, also provided updates, even if it was a simple rehashing of her travel itinerary for the day. In the era long before the internet, email or social media, the whole world was watching the best that it could.

As the journey progressed, horses and rickshaws and other exotic forms of transportation became increasingly important, and on one side trip Bly even visited a leper colony.

On Dec. 18, 1889, she arrived in Singapore, placing her exactly halfway around the world from where she’d left. By Dec. 24, she’d reached Hong Kong, and had her Christmas dinner there the next day.

Bly was feeling pretty good at this point, as she was about to board the Oceanic, a very new and very fast ship that she would meet in Yokohama, Japan, and sail on all the way to San Francisco.

Bly finally felt comfortable enough to inquire at a hotel about Bisland. The answer threw her.

“Oh yes,” she was told. “She was here three days or so ago.”

By Bly’s reckoning, that made them neck and neck. Then things got complicated. Where mail had been her savior in England, it became a stumbling block in Japan. The Oceanic was contracted to carry mail from China and Japan to the United States, and it had to wait until Jan. 7, 1890, for that mail to arrive — a five-day delay.

When she finally boarded the ship, a band onboard played “Hail Columbia” in her honor and the engineer posted a notice on the ship bulletin board that said, “For Nellie Bly, we’ll win or die.”

But her travails weren’t over yet. The Pacific Ocean was roiled by raging waves as huge storms racked the seas on their way toward the western United States. As the Oceanic moved ever closer to California, the forecast ahead grew bleak — blizzards lay ahead between her and the East Coast.

On Jan. 21, 1890, a flash was telegraphed to newspapers across the country, the Oceanic, with Nellie Bly among its passengers, arrived in San Francisco. Then, a new complication arose.

Somehow, a key piece of paper, the ship’s so-called “bill of health” had been left behind in Yokohama. That meant no one could leave the ship until another ship brought the papers east on the Oceanic’s behalf, a task that would take an estimated two weeks.

Bly was having none of this. Unwilling to lose the race now that she was so close to home, she threatened to jump overboard and swim to the dock if she had to; finally, after much back and forth, the Captain relented and she was put on a tug boat for shore.

The crossing of the continent was slow and hazardous, with numerous changes in trains and routes to try to navigate around the blizzards as best as she could.

At some points, tracks were completely obstructed by snow and had to be dug out before she could proceed, at another the train carrying her almost derailed when it struck a handcar abandoned on the tracks.

And yet the excitement continued to build.

In Colorado and Kansas suffragettes beseeched Bly to return and run for governor in their respective states. In Chicago, the Chicago Press Club feted her with a reception and breakfast, and in Pittsburgh, her final stop before heading to Jersey City, she reunited with family and old friends.

As for Bisland, she too finished her around the world voyage, but few pay attention to the person who comes in second, no matter how laudable their accomplishment.

Bisland was actually ahead of Bly and in England when she was told and apparently believed that she had missed her ride, the speedy German Steamer Ems, which was to carry her from Southampton back to New Jersey.

Whether she was actively deceived was never determined.

As it was, John Brisben Walker, her publisher, had bribed the shipping company to delay the Ems departure. But Bisland never knew this.

Instead, acting on the information she had, she traveled to Queenstown, Ireland, and caught a ride on a much slower ship, the Bothnia, thus assuring Bly’s victory.

Bisland’s ship did not arrive in Jersey City until Jan. 30, 1890. But she too completed her trip well ahead of Phileas Fogg’s fictional record, arriving back at her starting point in 78 and a half days.

A Welcome from the President

Two months later, Nellie Bly found herself in the East Room of the White House at a reception honoring various Americans.

The White House Press Corps reported that the room smelled of fresh spring flowers and most of the men and women in attendance were dressed in formal attire.

Some were even said to have snickered at the modest young woman in the midst, dressed in “a seal-brown walking dress, an astrachan shoulder cape and a close-fitting turban over which was spread a black dotted veil.”

No one, evidently, had realized the famous Nellie Bly was among them. No one, that is, except for President Benjamin Harrison, who stepped away from a receiving line to greet her personally.

“I am very much gratified to meet you, Miss Bly and I want to extend my congratulations on the success of your recent efforts to make a trip around the world,” he said, his face breaking into a smile.

Bly, the Washington Post reported, blushed profoundly, then happily accepted an invitation for her and her mother, who had accompanied her, to take a private tour of the White House.

When it was over, the two slipped out of the executive mansion and walked to the Washington Monument, and then on to the Capitol.

“I never get tired of sightseeing,” she said.

But her sightseeing in Washington wouldn’t last long. In deference to the wishes of a number of local ladies of consequence, Bly was scheduled to be the honored guest at an informal reception in the parlor of the Willard Hotel. By nightfall, hundreds were in attendance.

Marriage and a Change in Fortunes

Bly’s life would never be quite so happy or uncomplicated again.

After taking several months off to work the lecture circuit and tell the story of her exploits, Bly returned to the New York World in 1893 and essentially picked up where she left off, taking on investigative assignments writing about slums, labor abuses and corruption.

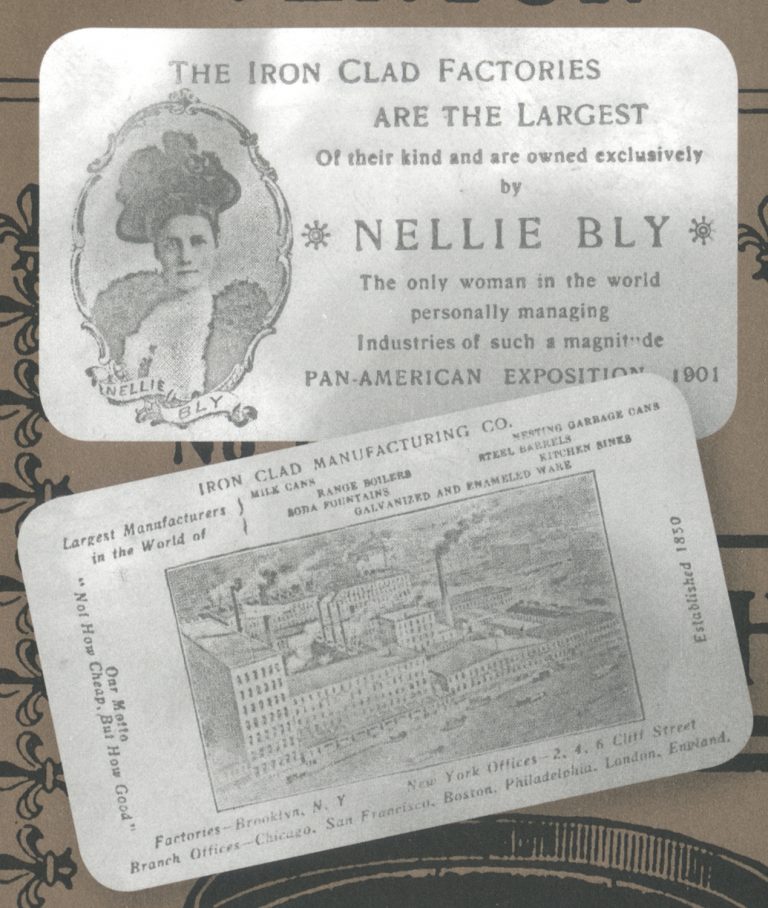

Then two years later, to the surprise of many, Bly suddenly became Mrs. Robert Seaman, her husband being 40 years her senior and president of both the American Steel Barrel Company and the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company.

The two had reportedly met on a train outside of Chicago, and decided they should marry just days later. Shortly afterwards, they established a home in a four-story brownstone located at 15 West 37th Street in Manhattan.

But the marriage was not without its difficulties. Despite her fame and successful career, Seaman’s relatives believed she was a golddigger and found ways to prey on his insecurities.

A few months after their marriage, Bly was in court, trying to convince a judge to prosecute a man her husband had hired to follow her.

“For the past three weeks my husband, who is for some reason unaccountably jealous, has been having me followed by three men,” she told a surrogate court judge in late 1895. “The man here is one of them and his actions last night are but a part of what I have put up with.”

Bly described how she had left home the previous night and found herself being followed around the city by the man in question.

She explained to the court that she disliked the food being served at her home and she ducked out at dinner time to restaurants her husband had selected for her and had long standing credit with.

“I am quite willing to submit to such an arrangement, but I object to having my every movement shadowed,” she said.

A contrite Seaman told the court he had never before had private detectives or anyone else in his employ track his wife, “and I am frank to admit that it was foolish of me to send Hanson out on Saturday night. It was a hasty act on my part and I am sorry I did it.”

“I have no intention of trying to obtain a divorce from my wife, and so far as I know, she has no desire to obtain a divorce from me,” he said.

After that incident, the couple seemed to reach a kind of equilibrium. Bly even got involved with the manufacturing company, and began designing products and attending to other aspects of the business.

In time, she became an inventor in her own right, receiving patents for a novel milk can and a stacking garbage can, both under her married name of Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman.

For a brief time she was one of the leading women industrialists in the United States but a combination of her own negligence and embezzlement by a factory manager resulted in the Iron Clad Manufacturing Co. going bankrupt.

The costly litigation that followed devoured her fortune.

Bly insisted that the company’s difficulties were entirely the fault of former employees who robbed her of large sums of money and that she was actively pursuing legal action against them that would make the company whole again.

The company’s creditors disagreed and pressed ahead with their legal action against Bly.

Instead of hiring a phalanx of lawyers to face off against the lawyers suing her, Bly decided to represent herself — and soon was facing contempt of court charges.

Sounding every bit like a person waging the fight of her life, Bly told a New York judge in 1912, “I am told that my conduct in court has not been all that is expected of a litigant and I regret that fact.

“While I do not ask any consideration on the grounds of sex … I may say that I have been under a physical and mental strain for something like two years that would have broken down many a strong man,” she said.

“To be forced to look helplessly on at the destruction of the property one has spent the best years of one’s life building up, to experience that following months of anxiety due to the events that precipitated the catastrophe … and then to have the additional disadvantage of being a woman pitted against a score of lawyers with all the resources of unlimited wealth behind them … and finally realizing that the strong arm of the law upon which one had been depending is but a reed … is not calculated to produce serenity of demeanor.”

Later, she said she was shocked by the notion of being held in contempt, insisting “How can I be in contempt of my only friend?”

“I may have been impudent on occasion, but I didn’t mean to be,” she said. “Perhaps I have done wrong, but it was only through a desire to fight the men who have slandered me in court and out. The representatives of the secured creditors have plotted to cheat me, wreck me, crush me. I have been told that I could be sent up for perjury. They have not treated me fairly, they have even served me with papers in court, which was not right. This case means 12 years of my life’s work wasted.

“I am not fighting the court, but these men,” she continued “They are powerful and I am weak. They have money and I have none. I have given my time, money, health, and, I fear, my mind to these proceedings.”

Bly said what really concerned her was the fate of her company’s unsecured creditors, and she vowed to fight for them, “until the breath leaves my body.”

“This is a fight to the finish against these men who are striving to ruin me,” she said.

And then, with the contempt charge still hanging over her head, Bly returned to journalism, joining the staff of the New York Evening Journal, and in the process, became the first female war correspondent to report from the front lines when she traveled to Europe to cover the outbreak of World War I.

For the next four years, she filed reports ripe with vivid descriptions of the carnage she was seeing.

“Through narrow, muddy, cobbled streets we crawled, weaving in and out of the endless lines of wagons coming toward us, bearing wounded soldiers mainly, though every once in a while a wagon filled with guns and knapsacks told its mute story of wet and water-filled mass graves,” she wrote in one dispatch.

In another, she wrote a “straggling stream of sick and wounded soldiers was always coming toward us. Sometimes they saluted, more often they staggered unconsciously and forlornly on, their sunken eyes fixed pathetically on the west, blind to their surroundings, their ears deaf to the near and ceaseless thundering of cannons, their nerves dead to the awful whizzing of the granades as they whirled above our heads, so near, yet never visible to the eye.”

In 1919, with the war coming to a close, she filed an emergency passport application in Paris. In it, she described herself as a reporter and said she’d been living at the Palace Hotel in Paris. Once back in New York, she was immediately arrested on the outstanding bench warrant and held on a $1,000 bond before the charge was ultimately dropped.

With that, she took up residence at the Hotel McAlpin on Herald Square in Manhattan and began writing a regular column for the Evening Journal, again telling the stories of the unfortunate, often with herself at the center of the action.

In fact, her last piece is about an execution, but the thing that lingers is the image of the cigarette she herself had given the condemned man.

Bly was just 57 when she contracted pneumonia in mid-January 1922, and she tried to fight it by taking to her bed for a few days.

When her condition only worsened, she was taken to nearby St. Mark’s Hospital, where she died the morning of Jan. 27, 1922.

Few mourners turned up to see Bly off during the solemn Episcopal ceremony said in her honor at New York’s Church of the Ascension. No crowds gathered to catch a last look at the once world famous celebrity as her casket was carried to the waiting hearse.

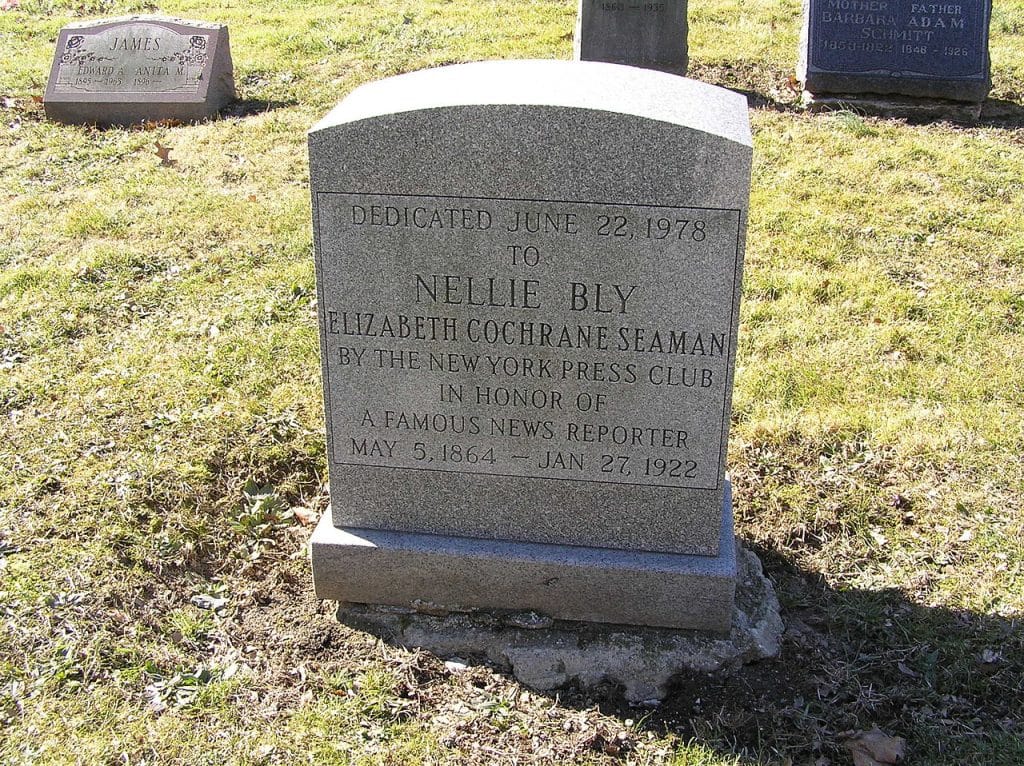

In fact her grave in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx would remain unmarked until June 22, 1978, when the New York Press Club finally erected a stone to remember her.

However, back in the city room of her last newspaper, the Evening Journal, one of her colleagues struck just the right note of admiration and respect as he tapped away at a final story about her.

“She was considered the best reporter in America,” he said.

Dan can be reached at [email protected] and at https://twitter.com/DanMcCue.