Researcher Develops New Weapon in War Against Overdoses: An Implanted Device That Automatically Releases Lifesaving Naloxone

CHICAGO — An opioid overdose can be a lonely death. People who use drugs often do so in private, and should they get a dose stronger than they can tolerate, no one will be there to save them with the overdose-reversing medication naloxone.

But now, a researcher at Northwestern University is developing a technological fix to that lethal conundrum.

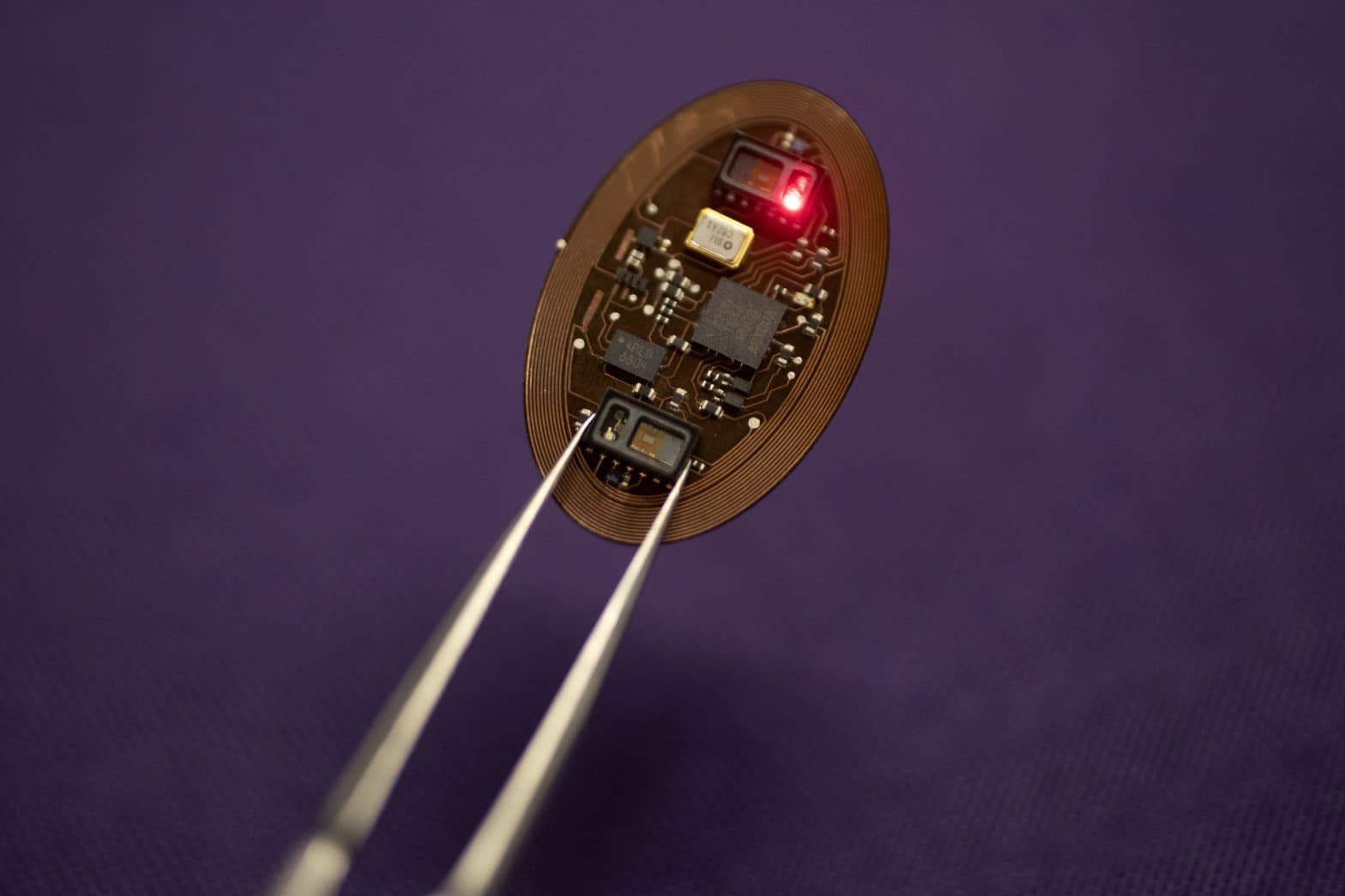

John Rogers, director of the school’s Center for Bio-Integrated Electronics, has helped to devise a gadget the size of a flash drive that can be implanted under the skin. If a sensor detects that a person’s blood-oxygen level has dropped to a dangerous level, it automatically releases a stored dose of naloxone.

“It’s a fully autonomous system, almost like an implantable emergency response system, providing a first responder’s type of functionality but without human intervention,” Rogers said.

The idea has won a $10 million grant from the National Institutes of Health’s Helping to End Addiction Long-Term Initiative, which aims to find scientific solutions to the opioid crisis. Animal testing is scheduled to begin in 2020, and clinical trials in humans could come within five years.

Rogers and a colleague, Robert Gereau of the Washington University Pain Center in St. Louis, have collaborated on numerous gadgets designed to monitor bodily processes and intervene when necessary. They include devices that electrically stimulate nerves, release chemicals into the brain and tame overactive bladders.

Attacking opioid overdoses was a natural extension of that work, Gereau said. Though numerous outreach efforts have put naloxone into the hands of drug users and their loved ones, Gereau said that approach has an obvious limitation.

“If someone’s alone and has an overdose, even if they have (naloxone) in their house, it’s not going to help them if there’s no one there to administer it,” he said.

Opioid overdoses depress breathing and cause unconsciousness, so the device Rogers and Gereau developed works automatically. Implanted beneath the skin, possibly in the small of the back, it will use sensors to monitor blood oxygen level.

If three straight readings come in below a preset threshold, an electrically triggered chemical reaction releases a dose of naloxone (each device will contain four). The device will also be tethered to a patient’s cellphone; a signal transmitted via Bluetooth will have the phone notify 911 that help is needed.

Rogers said the main clientele he envisions using the device are those leaving incarceration or drug treatment.

“The problem there is that before they are pulled off opioids, their bodies have developed a certain tolerance,” he said. “That tolerance fades when they’re off of opioids, so when they come back out, if they try to take opioids again, they can very easily receive an accidental overdose.”

Some drug treatment and harm reduction experts applauded the innovation behind the device, but suggested complications could arise in the real world.

Anthony Trotter, a former long-term heroin user who now works with a treatment program in Chicago’s East Garfield Park neighborhood, said privacy concerns could prevent people from getting the implant.

“(A user) might not be too keen about letting someone put a device in him, because a lot of times, people don’t really want their family to really and truly know they’re getting high,” he said.

Maya Doe-Simkins of the Chicago Recovery Alliance, which distributes clean needles and naloxone to people who use heroin, also thought privacy could be an issue, particularly since the device is engineered to automatically alert paramedics.

She said some low-tech interventions, such as easily accessible medication-assisted treatment and places where people can use drugs under supervision, could accomplish the same goal with less cost and intrusion.

“I find it interesting on an intellectual level, but it feels like a perfect example of how we’ve bypassed all the simple analog things we know absolutely work,” she said.

Dr. Gregory Teas, an addiction treatment specialist with AMITA Health, questioned whether the researchers are targeting the right clientele. He said some drug users have been known to dig naltrexone implants, which block the effects of opioids, from beneath their skin.

“(The naloxone implant) makes a lot of sense on the surface, but these are patients whose addiction still controls their behavior,” he said.

He said chronic pain patients might be a more stable population that could benefit from the implant. They can be subject to overdoses when they take large amounts of opioid pills, or mix them with other prescribed drugs that can cause dangerous reactions, he said.

Rogers himself brought up another possible issue.

“If a patient has one of these devices, won’t that make them more comfortable with pushing the limits?” he said. “That’s a valid concern. It’s something we’ve thought about. At the end of the day, I think the benefits will outweigh the risks.”

Gereau said while it will take work to ensure that patients are comfortable with the implants, he thinks it will be a valuable addition to the arsenal in fighting the overdose scourge.

“It won’t end overdoses,” he said. “But the goal of the (NIH) initiative it to reduce deaths, and this can certainly make a dent.”

———

©2019 Chicago Tribune

Visit the Chicago Tribune at www.chicagotribune.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

—————