The Security of the United States Military Depends on ‘Made in America’

COMMENTARY

Political leaders often talk about the importance of enhancing U.S. manufacturing. “Made in America” is a common campaign mantra that can always excite a crowd. As an American manufacturer, I have dedicated my career to producing critical aerospace components for both the defense and commercial aerospace sectors. “Made in America” is more than a slogan. It’s a way of life — for me and for millions of others throughout the country.

The American manufacturing sector produces family supporting jobs across our country. In fact, there are roughly 12.5 million manufacturing workers in the United States, representing more than 8% of total U.S. employment. Yet I am left to wonder how importantly Congress views the U.S. manufacturing sector and products that are “Made in America” when I see the debate over our national tanker fleet.

The U.S. Air Force has put forth its modernization plan to ensure America continues to have the world’s most elite aerial force. As part of that initiative, the KC-46 Pegasus tanker has been replacing the aging KC-135 Stratotanker, which is being phased into retirement. As the only tanker available that meets U.S. Air Force and Federal Aviation Administration safety requirements, the modernized KC-46 makes sense as the tanker of the next generation.

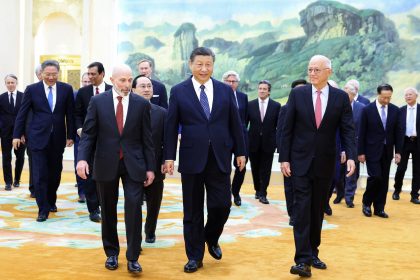

Despite the clear benefits of the KC-46, including its established and reliable American supply chain, certain leaders are looking to introduce the European-made LMXT tanker into consideration for the next iteration, known as KC-Y. The debate is set to begin in spring 2023. From an American manufacturing standpoint, adding a foreign tanker would risk the security of our military forces and result in layoffs of U.S. workers. A derivative of the Airbus A330, the LMXT is produced in European countries: England, France and Germany and has subcontractors in countries around the world, including China.

As an American manufacturer, I urge Congress and the U.S. Air Force to seriously consider the risk to security and overall costs of adding a foreign tanker to the fleet — costs that include the loss of American jobs, the destabilization of the supply chain and the risk of exposing military secrets and defense strategy.

The World Trade Organization consistently found that the European Union subsidized more than $18 billion of support to Airbus, resulting in a loss of American business and American aerospace jobs. Despite a favorable ruling for the United States in the WTO dispute, Air Force and congressional leaders would hand that victory back to Europe if the LMXT was introduced into our tanker fleet.

Airbus touts its partnership with American companies but the fact remains that the LMXT will be built in Europe just like every other Airbus tanker, with only limited final assembly and modifications done in the United States.

A serious issue we also must consider is this: Throughout the COVID-19 crisis, our nation’s eyes were opened to the true importance of homegrown supply chains. How can we risk forgetting such an important lesson so quickly?

American businesses like mine understand the privilege and importance of providing manufactured goods to U.S. military programs. Should the United States introduce a foreign aircraft and foreign supply chains with ties to American adversaries like China? Our national defense would be at the mercy of foreign manufacturers who do not have America’s best interests in mind.

So, what is the consequence of adding the foreign-made LMXT to the U.S. tanker fleet? Putting our military security at risk, loss of American jobs and an unreliable supply chain. Congress and military leaders must ask themselves, is a security risk to our military forces and America worth a short-term, cost-only mindset?

Clay Parrill is the owner of Electrocube, a U.S.-based electrical components manufacturing company in Pomona, California. He began his career in the automotive processing industry and leveraged his engineering and manufacturing expertise to lead Electrocube since the 1990s. Electrocube can be reached on LinkedIn.