Recalling the Pentagon Papers Case, 50 Years On (Part One)

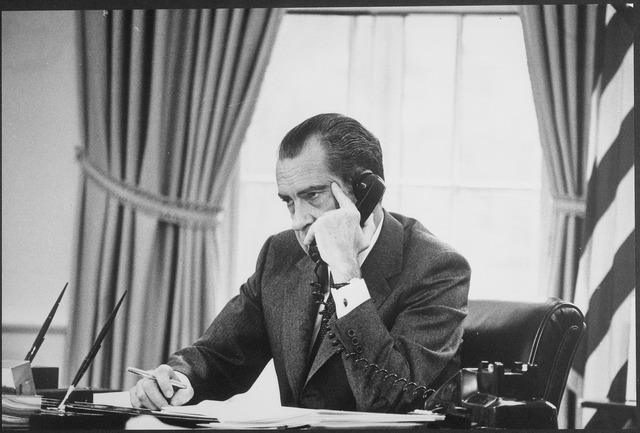

The battle was joined on a Monday night. It was shortly after 7 p.m. on June 14, 1971, when a seething President Richard Nixon telephoned his attorney general, John Mitchell, and told him it was time to make the administration’s position clear to The New York Times in no uncertain terms.

For two days, The Times had been publishing documents included in a detailed, classified Pentagon study that revealed numerous secrets about America’s conduct in Southeast Asia and the lies that allowed for the expansion of the Vietnam War, even after many of those doing the lying had concluded the war was unwinnable.

Adding insult to injury, the first stories, under the banner headline, “Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces 3 Decades of Growing U.S. Involvement,” appeared alongside accounts of Tricia Nixon’s marriage to Edward Cox, a scion of a wealthy and influential Republican family, in a Rose Garden ceremony at the White House.

After working out the text of their message, Mitchell immediately wired it — via a telex, a precursor of the Fax machine — directly to the offices of The Times in midtown Manhattan.

The tone of the dispatch was respectful, but direct. Mitchell, the highest law enforcement authority in the land, accused The Times of having violated the Espionage Act.

He called upon the newspaper to halt further publication, which, he said, would cause “irreparable injury to the defense interests” of the nation.

He also demanded that the newspaper — which prided itself on being America’s paper of record — return the classified documents to the Defense Department immediately.

Two hours later, a return telex signed by Harding Bancroft, executive vice president of The Times, said the paper would “respectfully decline” the attorney general’s demand “for the same reasons that led us to publish the articles in the first place.”

The next day, for the first time in American history, the White House sought — and won — a temporary court order barring a newspaper from publishing a news article.

On June 30, 1971, after 15 days of legal wrangling and amid a firestorm of publicity, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 against the government.

The very next day, the Times, The Washington Post and other newspapers involved resumed publication of what had already become known as the Pentagon Papers.

A Divided Nation, A Divisive War

In 1971, as now, America was a deeply divided nation. Disputes over the Vietnam War and civil rights were raging. The Kent State killings of four students by National Guardsmen was less than a year old.

Against that backdrop, opinions about whether The Times, The Washington Post and others should continue to publish documents obviously stolen by a leaker was equally divided.

Opponents of the war wanted the articles and their revelations to keep on coming. Supporters of the war and the president, couldn’t have been more harsh in their denunciations.

So what were the Pentagon Papers and what, after 50 years, is their enduring significance to us today?

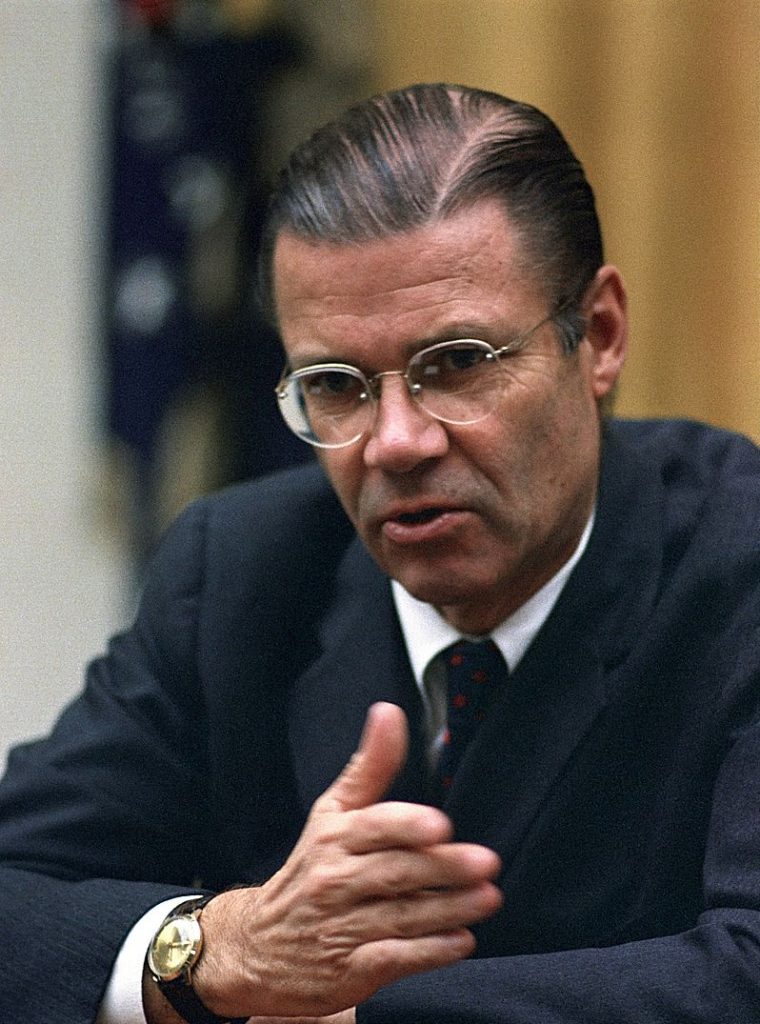

By mid-1967, then-Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, a one-time Vietnam hawk, had become deeply disillusioned with the war, considered it a failure, and believed future historians would need a detailed history of the war to avoid repeating mistakes.

His initial intention was to have a handful of researchers work a matter of weeks on the project.

Eighteen months later, a group he formed called the Vietnam History Task Force, had expanded to several dozen people and had produced more than 3,000 pages of analysis with an additional over 4,000 pages of documents, all of it spread over 47 individual volumes.

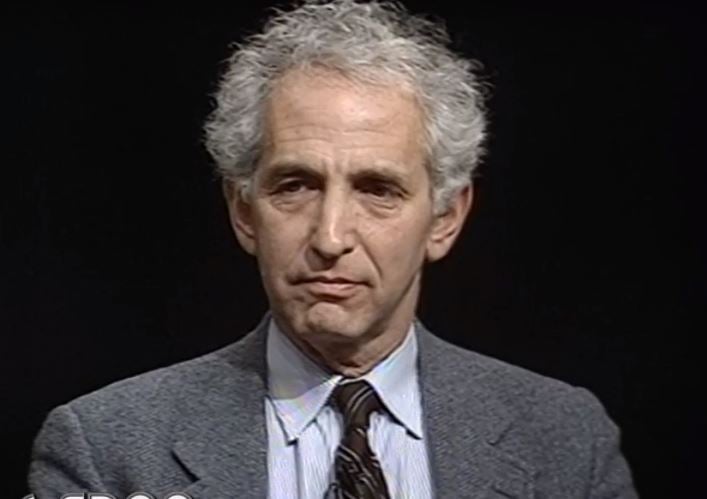

Among those who wrote the study and had complete access to it was a former Marine and young economics expert at the Rand Corporation named Daniel Ellsberg.

Like McNamara, Ellsberg had been an outspoken supporter of the war, but after spending two years in Vietnam himself and seeing first-hand what was going on there, his opinion changed dramatically.

Convinced the release of the Papers would hasten the end of the war, the analyst went rogue and blatantly broke his employment agreement with Rand by xeroxing all but four volumes of the report, covering the word “classified” on the bottom of each page with a white piece of tape.

Ellsberg initially tried to give the documents to anti-war lawmakers on Capitol Hill, including Sens. William Fulbright and George McGovern, in the hope they would hold hearings exposing how Nixon was continuing his predecessors’ pattern of lying about the war’s expansion.

At least, he thought, getting the documents into the right hands would result in their getting entered into the public record.

Instead, he was rebuffed, mostly on the grounds that involvement with a secret cache of stolen documents would no doubt be a career killer for any lawmaker who brandished them in a committee room or the well of Congress.

Ellsberg decided his next option was to turn to the press.

After reading an anti-war essay in The Times by reporter Neil Sheehan, Ellsberg believed he had his man. The two had met briefly while Sheehan was a UPI correspondent in Vietnam, and had since struck up a casual, intermittent relationship as source and reporter.

Now Ellsberg was calling with something urgent on his mind, and the two men agreed to meet at an apartment in Cambridge, Mass.

An Act of Betrayal

History tells us that Ellsberg “handed the papers to Sheehan” … and that by the time their initial meeting was over, Sheehan was in possession of five shopping bags of xeroxed documents. It also tells us the entire package weighed 60 pounds.

But the passage of five decades — and the death of one of the protagonists — has led to revelation of an alternative version of the story.

Shortly before he died, at the age of 84 and on the day after the Capitol Hill riot in January, Sheehan sat for an interview with The Times’ Janny Scott for an article that he insisted be published only after his death.

“Beset by scoliosis and Parkinson’s disease,” Scott wrote, Sheehan spoke for nearly four hours in his Washington home, telling “a tale as suspenseful and cinematic as anyone in Hollywood might concoct.”

“Contrary to what is generally believed,” Sheehan told his colleague. “Mr. Ellsberg never ‘gave’ the papers to The Times.”

What really happened Sheehan admitted, was that he defied the explicit instructions of his confidential source, who had told the reporter he could read the documents and make all the notes he wanted, but that he could not make any copies.

Sheehan recalled being “quite upset” with the restrictions, as he believed Ellsberg had already agreed to give him the papers.

Ellsberg was adamant. While he wanted Sheehan’s help, he’d come to believe that once The Times had the papers, it would do what it wanted with them, whether it served his goal of ending the war in Vietnam or not.

The two men sparred over their disagreement. Then, believing they had a deal, Ellsberg left Sheehan alone in the apartment to begin reading the papers for the first time.

Returning home to Washington the next day, Sheehan confided in his wife, the New Yorker writer Susan Sheehan, about what he’d seen and the position Ellsberg had put him in.

Her advice was that he “get control” of the situation. “Xerox it,” she said.

When Sheehan returned to Cambridge to continue reading and taking notes, he still had no idea how he’d accomplish this; then Ellsberg announced he was leaving on a vacation.

Sheehan asked to keep working with the documents and Ellsberg agreed, giving him a key to the apartment, but reminding the reporter in no uncertain terms — “you are not to make copies.”

“I’d known Ellsberg for a long time, and he thought I was operating under the same rules that one normally used: Source controls the material,” Sheehan told Janny Scott. “He didn’t realize that I had decided: ‘This guy is just impossible. You can’t leave it in his hands. It’s too important and it’s too dangerous.’”

Once Ellsberg was on his way, Sheehan called his wife and asked her to join him in Massachusetts, bringing extra suitcases, envelopes and all the loose cash they had in their home.

They checked into separate hotels under fake names, and together they tackled the massive copying effort, first in the local real estate office of a friend, then later, in a suburban copy shop.

As the copying continued, they stashed piles of pages in a locker at the Boston bus terminal, and later, in a locker at Logan airport.

When they were done, the Sheehans bought an extra seat on their flight home and piled their suitcases onto it, buckling them in rather than letting them out of their sight.

“You had to do what I did,” Sheehan told Scott.

Years earlier, Ellsberg had recounted at least part of the same story. He said he had stashed the secret documents in the Cambridge apartment and given Sheehan a key in March of 1971.

He also confirmed he had told Sheehan he could take notes but not make his own copy of the papers “unless and until someone high up there had decided the newspaper was ready to publish, and to publish large quantities of them.”

As it happened, Ellsberg was blindsided by the initial publication of the papers. He and Sheehan wouldn’t speak for months, and never again as reporter and source.

Ellsberg, who recently turned 91, was unperturbed in January when he learned of the depth of Sheehan’s duplicity.

“Then and now, who better understands that there are very strong procedural, moral and ethical rules that have to be re-examined and in some circumstance violated?” he told reporters.

And regardless, he said, “it all came out all right in the end.”

(The story of the Pentagon Papers continues in Part Two with The New York Times fateful decision: “To Publish or Not to Publish.”)