Can AM Radio Be Saved? Should It Be?

WASHINGTON — Nearly 60 years after an edict by the Federal Communications Commission inadvertently began the long, slow decline of AM radio, Congress suddenly appears to be besotted with a broadcast band many radio listeners left largely for dead decades ago.

In just the past month two bills, one in the House and one in the Senate, have been introduced to force automakers to maintain AM broadcast radio in new vehicles at no additional charge to consumers.

The bipartisan House bill, the AM for Every Vehicle Act, is sponsored by Reps. Josh Gottheimer, D-N.J., Tom Kean, Jr., R-N.J., Rob Menendez, D-N.J., Bruce Westerman, R-Ark., and Marie Gluesenkamp Perez, D-Wash.

A companion bill has been introduced in the Senate by Sens. Ed Markey, D-Mass., and Ted Cruz, R-Texas.

The bills come after eight of the world’s 20 leading vehicle manufacturers announced plans to remove AM radios from their cars and trucks as they transition from making fossil fuel-powered vehicles to new models powered only by electricity.

The proposed legislation — and the future of AM radio more generally — will be the subject of a House Communications and Technology Subcommittee hearing next Tuesday, June 6, in the Rayburn Office Building.

“What you’re seeing is a coming together of a bipartisan, bicameral coalition to save AM radio because AM radio is our source for news and for weather and sports and entertainment, and it is our emergency alert system,” Markey said during a recent Zoom call with reporters, seeking to explain the sudden surge in interest.

“It’s a crucial part of our diverse media ecosystem … and its benefits are obvious to the 47 million Americans who tune in every week,” he continued. “We cannot allow this resilient and popular communication tool to become a relic of the past.”

A Moment A Century in the Making

In contrast to newer and flashier technologies like satellite and HD radio, AM radio has its roots in the earliest days of the 20th Century.

Most trace its roots to 1906, when Dr. Lee de Forest, a cantankerous but brilliant inventor, fashioned the “Audion,” the vacuum tube that made radio, television and a host of subsequent technological innovations possible.

An obsessive whose myopic vision often blinded him to the effect he was having on others, de Forest was asked to leave Yale because his experiments were wreaking havoc on the campus and disturbing other students.

Later, he was turned away by the more established inventors Nikola Tesla and Guglielmo Marconi, who feared his jarring presence would disrupt activities in their labs.

They were likely right. Although he’d secured more than 180 patents during his lifetime, de Forest’s career was marked by tumult, frayed relationships and failed businesses. Near the end of his life he even boasted about the fact he had made — and later lost — several fortunes.

In the early 1900s, de Forest was seeking a way to turn a weak electric signal into a stronger one — a prerequisite to the growth of a nationwide telephone industry — when he made his breakthrough.

He was far from the only scientist working in this area, but in many respects he was among the most single-minded.

Hunkered down in a tiny laboratory on lower Park Avenue in New York City, he immediately recognized that his vacuum tubes were vastly superior to those that had come before, and held the potential to do far more than amplify telephone calls and ship-to-shore communications, another important consideration in the early 20th century.

He soon came up with a primitive system to send, receive and amplify very low frequency electromagnetic waves, and began modest, unpublicized experiments with the device. The first radio broadcast in history consisted of de Forest sending his voice from one side of his lab to the other.

Then, while taking a rare break from his work on a summer afternoon in 1907, he ran into Eugenia Farrar, a popular young opera singer of the era, and enlisted her help in carrying out a far more ambitious experiment.

As de Forest recalled during a dinner in his honor at the 1939-40 New York World’s Fair, he asked Farrar to sing into a horn attached to his device, assuring her that the sound of her voice would be heard at listening posts he had arranged for at the Brooklyn Navy Yard and on Staten Island.

“You mean to say, all I have to do is sing, and they will hear me all the way over in Brooklyn?” de Forest recalled the 34-year-old singer asking in disbelief. Sure enough, not long after her impromptu recital ended, listeners at both remote locations reported hearing her rendition of “I Love You Truly.”

De Forest had proved his concept, but also saw that refinements were necessary if his device were to have any practical use. It was another three years before he was ready to try again.

On Jan. 13, 1910, in a highly publicized test, he broadcast the Italian tenor Enrico Caruso from a new, larger laboratory located in the Highbridge section of the Bronx, and followed that, a month later, with a performance by Mariette Mazarin of the Manhattan Opera Company.

Still, de Forest’s ambitions continued to outstrip his invention. He dreamed of regular opera broadcasts, but didn’t achieve anything of the kind until late in 1916.

By then his contraption, which required earphones to listen, had caught the public’s fancy. It also caught the attention of the entrepreneurs and hustlers with whom de Forest would wage legal battles for decades.

Perhaps the most significant of these was David Sarnoff, who as a youth, entered a downtown office building to apply for a copy boy job at the New York Herald newspaper, but walked through the wrong door and wound up being hired as a low level “assistant” and wireless operator trainee by the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America.

Sarnoff himself would later spread the likely apocryphal tale that on the night of April 14, 1912, as he worked at a wireless station Marconi had installed atop the Wanamaker department store building on Ninth Street and Broadway, he was among the first to learn the Titanic crashed into an iceberg in the North Atlantic.

According to Sarnoff and others who repeated the story, he then spent the next three days interpreting Morse code messages from the Carpathia and other rescue ships converging on the scene.

It is beyond question, however, that Sarnoff did not lack ambition. In 1915, while still but a minor member of the staff, he penned a memo to his superiors boldly urging them to mass produce a home radio receiver.

“I have in mind a plan of development that would make radio a household utility in the same sense as a piano or phonograph. The idea is to bring music into the home by wireless,” he wrote.

Sarnoff’s bosses did not embrace the idea.

“They considered it a harebrained scheme,” he said later.

However, eventually worn down by Sarnoff’s persistence, they agreed to provide $2,000 (about $45,594 today) to produce his proposed “radio music box.” By 1924, the company was rebranded as the Radio Corporation of America, and the once-dismissed music box had earned it more than $83 million.

Two years later, RCA formed the National Broadcasting Company so it could feed programs to a number of interconnected radio stations. It was the first radio network in the country.

By the mid-1920s, the radio “craze” had become a fact of many people’s lives, with more than 46% of American homes having a receiver.

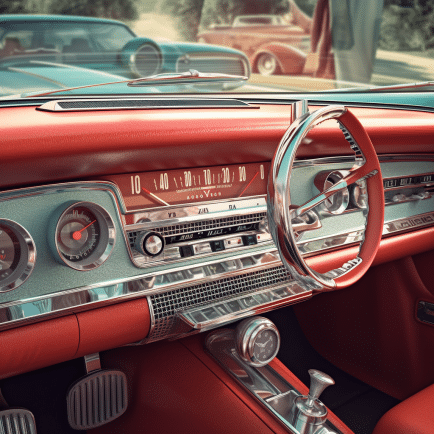

So avid were these listeners, that in 1930 Galvin Manufacturing Corporation created a whole new market by introducing the first successful car radio — the first product to bear the Motorola name, a combination of “Motor” and “Victrola” — Victrola being the brand of the first consumer phonograph.

Big Doings in Pittsburgh

Of course, New York City wasn’t the only setting for breakthroughs in early radio.

About 400 miles west of de Forest’s lab, a young man named Frank Conrad was working as an assistant chief engineer of the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Tall and lanky, the son of a railroad mechanic, Conrad’s restless mind had made him a poor student, and as soon as he was able, he abandoned his formal education for a job as a bench apprentice at a new research laboratory in the city.

Similar in intent to Thomas Edison’s lab in West Orange, New Jersey, the facility George Westinghouse established in Pittsburgh’s Garrison Alley hired both serious, academically-trained scientists, and a small number of eccentrics and mavericks.

In such an environment, Conrad prospered, quickly becoming one of the company’s most productive inventors.

But radio wasn’t among his daily pursuits. The story handed down through the decades is that he built his first wireless receiver in 1912 to win a $5 bet about the accuracy of his $12 watch.

To do this, he tuned in each day at noon to compare his watch’s time to the 12 o’clock signal issued from the master clock at the U.S. Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C.

His bet won, Conrad found himself with a dilemma.

He’d become increasingly interested in wireless communications, but was not adept at the Morse Code wireless operators used to “talk” to one another. To overcome this, he added a microphone to his homemade radio. His simple work around proved revolutionary.

Until Conrad set up his microphone, radio was primarily a means of communicating with just one other wireless operator at a time. And then, you had to be able to type out the same dot-and-dash based language. With a microphone and a human voice, Conrad realized, you could talk to anyone who was listening.

Intrigued by the possibilities and encouraged by the enthusiastic response he received, Conrad built a 75-watt transmitter in his garage, and took out a license with the U.S. Department of Commerce. He began informal broadcasts of local news and weather — along with a smattering of selections from his personal record collection — in 1920.

When he ran out of records he borrowed some from a local music store, which stipulated he must tell his listeners where he got them — the first “sponsored broadcast.”

“It was a hobby I carried out at home,” Conrad said in an interview recorded upon his retirement from Westinghouse in 1940.

“It’s one of those things,” he continued. “As I got deeper and deeper into it, people would call me up at night and ask me to transmit, saying they had friends over who wanted to hear something come out of the air …”

Eventually, due to the frequency of such requests, Conrad began “transmitting” every Wednesday and Saturday night.

“That started the first regular broadcasting, and of course, I had no idea what it was going to turn into,” Conrad said.

After Conrad died in December 1941 following a heart attack, The New York Times wrote, “One day a department store advertised sets on which you could hear the Conrad programs. This advertisement gave the inventor an idea. He in turn gave the idea to the Westinghouse publicity department. Westinghouse got a license for Station KDKA from the federal radio authorities, a new station was built at East Pittsburgh and commercial radio was launched.”

KDKA’s first broadcast was Nov. 2, 1920, and consisted entirely of reporting presidential election night results in the race between the Republican and eventual victor, Warren G. Harding, and his fellow Ohioan, Democrat James M. Cox.

Listened to nearly a century later, the recording of that night reverberates with excitement. One senses the apprehension in the announcer’s voice as he strives to enunciate each syllable of every word. Adding to the sense of how novel and unpolished the whole affair was is the throat-clearing and other “mistakes” that were allowed to go out over the air.

A photograph of the event reveals that the four men announcing the outcome of the election all dressed in suits for the occasion. The returns came from the Pittsburgh Post and Sun newspaper, whose editors had been asked to relay the latest tally by telephone as soon as it came in.

“We’d appreciate it if anyone hearing this broadcast would communicate with us,” the announcer said before the vote count began rolling in. “We are very anxious to know how far the broadcast is reaching and how it is being received.”

No one can say with certainty how many people heard the broadcast, but the best estimates at the time suggest as many as 100 listeners in Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia tuned in.

Word of the broadcast created a sensation, and soon KDKA would increase its transmitter to 500 watts, a boost in power allowing it to be heard nearly everywhere in the U.S. east of the Mississippi River and in parts of Canada.

The Golden Age of Radio

From such humble beginnings, AM radio grew to be the dominant method of broadcasting and would remain so until television came fully on the scene in the early 1950s.

Suddenly, or so it must have seemed at the time, television began to siphon off all the kinds of programming — from soaps to comedy shows and musicals to news — that radio had pioneered.

By the time “Uncle Miltie” and “I Love Lucy” were entertaining millions of families from a little video box in their living room, hundreds of radio stations across the country were being forced to innovate in some fashion or die.

Critical to AM radio’s future was the development of the Top 40 format.

It was born, the story goes, after an aspiring radio magnate named Robert Todd Storz and his assistant, Bill Stewart, at KOWH in Omaha, Nebraska, decided to walk to the bar across the street from the station for a drink.

Up to this point, both Storz and Stewart, like many independent radio men across the country, were students of WNEW-AM in New York City. An independent station established in 1934, WNEW would be responsible for a number of innovations, not the least of which was employing the industry’s first notable disc jockeys and inaugurating overnight programming.

For Storz and Stewart, the main thing they pilfered from WNEW was its approach to block programming, an easy-to-follow formula of broadcasting carefully selected recordings in solid segments across-the-board.

But as they sat and talked on this particular night in the bar in Omaha, the two men were struck by the fact the same songs were repeatedly being played on the jukebox.

“Near closing time, a waitress walked over to the jukebox, took change from her pocket and played the same song three times in a row,” Storz remembered years later.

The night turned out to be a revelation for the two men. Though KOWH sought to cater to its listeners’ tastes, they’d never realized how often people were willing to hear the same song if it appealed to them.

Their fellow patrons at the bar convinced Storz and Stewart that familiarity with the music was the key to getting listeners to continue to tune in. Returning to the station the next day, they began to hash out a new approach to programming the station.

As they brainstormed, the broad outlines of a format were born. They would reduce the number of records played on the station, and repeat listener favorites more often. At the same time the station itself would designate a “pick of the week” — typically the current number one hit across the country according to Billboard magazine — which would be played once an hour.

The Top 40 format was further refined during the 1950s by Texas pioneer Gordon McLendon, founder of the Liberty Radio Network, who introduced the idea that disc jockeys should be distinct, high-profile personalities in their own right and that the new Top 40 music shows should also incorporate brief newscasts.

Thanks to his elevation of the disc jockey to celebrity, McLendon’s KLIF in Dallas quickly became the city’s top-rated station. To further pump up its ratings, McLendon spent thousands on contests and promotions to continually stoke audience interest.

Within a decade, and with the not inconsiderable help of The Beatles and the 1960s pop and rock explosion, Top 40 would take the nation’s major metropolitan areas by storm, reviving AM radio’s fortunes … until the proverbial roof fell in.

FCC Edict Kick-Starts the FM Era

In July 1964, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson, the National League won the 35th annual Major League Baseball All-Star Game held at the new Shea Stadium in New York, and the Beatles triumphantly returned to their hometown of Liverpool on the heels of their first U.S. tour to attend the premiere of their first film, “A Hard Day’s Night.”

Amid all this, in a government board room on a warm and drizzling Washington, D.C., afternoon, the Federal Communications Commission decided it was time — after years of talk and deliberation — to shake up the radio industry like it had rarely been shaken before.

The vehicle was a new set of rules providing that jointly owned AM and FM outlets in cities of over 100,000 population must cut their program duplication to 50% or less of FM broadcast time.

As explained by the commission, the move was intended to stop the waste of channels on the FM band and to give rise to greater programming diversity.

At the time of their issuance, the rules affected more than 330 AM and FM station pairs serving metropolitan areas across the United States.

The initial date for compliance was Aug. 13, 1965; a deadline later put off until Jan. 1, 1967.

Whenever the rule went into effect, industry observers nevertheless saw it as a sea-change in the attitude of the commission, which previously had been seen as forsaking FM for the benefit of the politically-connected AM station owners.

Finally, some 30 years after its invention, FM would be given a chance to come into its own as a broadcast service.

That was the insider’s view; for anyone outside of radio, word that a Washington regulator had decided an abstract something was hardly gripping news.

Billboard, which ran an extensive piece of the FCC’s action on Aug. 8, 1964, framed the story two ways: as a long overdue reshuffling of the radio market, particularly in major cities, and as a likely boost to the already-rising sales of FM radios.

The non-duplication rule also redressed a grievance that extended almost all the way back to Edwin Armstrong’s invention of “frequency modulated radio” or FM, in 1933.

Armstrong, who had already experienced the heady highs and gut-wrenching lows of the inventor’s life by the time he made his breakthrough in the basement of Philosophy Hall at Columbia University, was destined to spend the remainder of his life engaged in litigation over one rival inventor’s claim or another.

FM radio, he thought, would be different. All anyone had to do was experience spectrum’s superior quality in comparison to AM, and the technology was sure to flourish, he believed.

But when he unveiled his invention at a 1935 meeting of the Institute of Radio Engineers at Columbia, he got perhaps the rudest shock of his life — vehement opposition by his then-friend the aforementioned David Sarnoff, who was then the president of the Radio Corporation of America.

What Sarnoff wanted to see at the demonstration were advances in AM technology that would enhance the substantial investments his company had already made; if FM came to the fore, Sarnoff believed his many thousand AM transmitters would be obsolete and his broadcast network would have to be rebuilt from scratch.

He then set about squashing the new technology, seeking to bury it in a flurry of publicity about another breakthrough, television.

Armstrong’s response was to request a license for an experimental FM station he planned to establish in Alpine, New Jersey. That request was denied until he threatened to take his technology to another country, but even when he got his license, his problems with Sarnoff — by now his full-blooded nemesis — were not over.

After Armstrong rejected an offer from RCA to buy his license, Sarnoff directed his engineers to develop their own FM radio technology and radios, prompting Armstrong to file a series of patent infringement lawsuits.

And it wasn’t the only front on which he was fighting.

When commercial FM radio started rolling at the end of World War II, the FCC, after a bitter fight, agreed to permit the duplication of AM broadcasting on FM stations.

For the AM stations, the decision meant a reduced number of potential competitors and also gave them a bone to toss potential advertisers, time on their FM affiliates, as a bonus for buying time on AM.

Put simply, FM got caught in a bind.

While the sound of FM was undeniably “better” than that on the AM band, having no static and a higher fidelity; FM receivers were far more expensive than AM radios, and in the simulcasting environment, this left consumers with the impression they would effectively be choosing to pay more to listen to the same programming.

As Billboard’s David Lachenbruch wrote, “What kept FM radio from becoming a mass-market item was that it offered very little that was new and different.”

True, there were some independently-minded FM station owners who made a go of it with specialized programming — mainly classical, jazz, folk and some talk — but they were forever waiting for a shift in public tastes they could do little to foster on their own.

In one fell swoop then, the FCC had changed everything.

“To get an idea of what will happen when independent AM and FM programming goes into effect, look at the New York market,” Lachenbruch wrote.

By his reckoning, the city was home to 35 stations, seven exclusively on AM, eight exclusively on FM, and 10 that simulcast on both.

“The FM band in New York will get, for all practical purposes, nine new stations,” he continued, noting that one AM station with an FM affiliate already featured distinct programming at night.

“The new ruling means the end of FM’s stepchild status as an appendage to AM …” he declared. “The FCC rule means the beginning of a new role for FM — a complete and distinctive broadcast medium.”

Sarnoff, who died in New York at the age of 80 in 1971, lived to see — and profit from — the revolution Armstrong had wrought; the inventor didn’t come close.

Tired after years of litigating against Sarnoff and others, by the early 1950s Armstrong began to exhibit increasingly erratic behavior. On one occasion, he insisted health problems he was experiencing were due to someone poisoning his food, and in what proved to be a final decisive event, he lashed out and struck his wife with a fireplace poker, an attack that forced her to leave him and stay with relatives in Connecticut.

Despondent over what he had done, on Jan. 31, 1954, Armstrong sat down and penned a two-page letter to his wife, saying he was heartbroken telling her he would forever be sorry.

He then dressed, put on a hat, overcoat and gloves, and after removing the air conditioner from an apartment window 13 floors above East 52nd Street, jumped to his death.

A maintenance worker found his body the next morning on a third-floor balcony.

In the wake of his death, his widow was finally able to prevail in court, successfully establishing Armstrong as inventor of at least five of the FM-related patents under dispute at the time of his death.

By 1964, FM was clearly on the rise. According to the annual report issued by the FCC that year, the agency had authorized FM stations in every state and sales of FM receivers had risen dramatically over the previous several years.

Trade figures cited in the report put the total number of FM receivers manufactured in 1958 at 764,000. By 1963, the last year for which statistics were available at the time, the number had climbed to 2.8 million.

The non-duplication rule “[o]bviously … means FM’s biggest growth period is still ahead,” Lachenbruch opined in the pages of Billboard.

Never again would FM have to be promoted on the basis of its superior sound and lack of static; “The big deal now is more programs, better choice,” Lachenbruch wrote.

AM radio almost didn’t know what hit it.

Speaking to broadcasters at an industry gathering in Washington, D.C., six weeks after the deadline for compliance, FCC Commissioner Robert Lee said the non-duplication rule and advances in technology had freed FM from the dominance of AM broadcasting.

“For far too long AM radio has been leading FM radio around by the nose,” he said, adding he believed the situation had stymied the development of stereo technology — a nonstarter for AM — as well as the creation of quality programming by media companies that were more interested in the profits that came with “banging away at the teenage audience.”

Lee predicted the non-duplication rule would result in “a shot in the arm” for the audio industry and result in advances that would allow FM to “run AM ragged if not out of business.”

Realizing the harsh sound of his words to many in the room, Lee allowed that he didn’t hate AM or its proponents. “But I am disgusted with its past dominance over the far superior medium of FM.”

He added, perhaps for the benefit of the journalists in the room, that he’d emphasized the phrase “past dominance,” as he was confident “That it’s all over now.”

Talk Talk

Indicative of what happened next is the story of WABC-AM in New York. The station embraced the Top 40 format and began playing pop music for mostly young ears in late 1960, and within five years, it dominated the market.

Year after year its share of the New York radio audience often topped 30% — numbers unheard of for a terrestrial radio station in the decades since.

But in opening up FM, the FCC’s non-duplication rule had a wholly unintended consequence — it effectively set the stage for FM album-rock radio, and with its arrival, WABC-AM’s audience steadily began to drift away.

The same thing happened to former AM radio powerhouses all across the country, and by 1979, FM radio had actually achieved parity, in terms of profitability, with its AM counterpart.

WABC and all big city AM radio was in free-fall.

On Monday, May 10, 1982, WABC-AM stopped playing music altogether.

To say goodbye, the station had two of its most popular disc jockeys from its glory days, Dan Ingram and Ron Lundy, host a three-hour farewell show.

The last song they played before the format change that noon was “Imagine” by John Lennon, followed by the sound of one of the “Chime Time” jingles the station had played constantly in the 1960s.

After a few seconds of silence, the station’s new “all-talk” format was on the air.

What’s interesting about that moment and others like it across the AM dial, is that at the time, no one had any idea what “talk radio” should be.

In WABC’s case, it was initially a mixture of personal finance, advice and public affairs shows, mixed with a smattering of political talk shows.

Lynn Samuels soon became the voice of progressive New York, while Bob Grant became the city’s conservative angry white man, spewing invective and hanging up on callers who disagreed with him.

Then, Rush Limbaugh came to town.

He had been a failure. Born in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, Limbaugh bounced from radio station to radio station in the Midwest, being fired within weeks or months from each one.

At one point things got so bad for Limbaugh — then an aspiring “shock jock” à la Don Imus or Howard Stern — that the general manager of one of his employers, KQV in Pittsburgh, suggested he chuck his on-air ambitions and became an advertising sales rep instead.

Finally landing in Kansas City in the mid-1970s, Limbaugh was handed a weekend public affairs program that aired on Top 40 station KUDL. The job didn’t last long, but it marked the emergence of Limbaugh’s conservative and sometimes controversial style.

After a stint in group sales for the Kansas City Royals, and more firings from radio stations, Limbaugh landed at KFBK in Sacramento, California, where “The Rush Limbaugh Show” was born.

His timing — the show launched in October 1984 — was perfect.

Less than three years later, the FCC repealed the fairness doctrine, which had required that stations provide free air time for responses and opposing views to any controversial opinions that were broadcast.

The decision was vehemently opposed by many members of Congress, who thought the agency was pre-empting their authority.

In short order, Congress passed the Fairness in Broadcasting Act of 1987, but the legislation was vetoed by President Ronald Reagan, and lawmakers on Capitol Hill were unable to muster enough votes to overturn it.

Limbaugh thrived in the new, politically-unencumbered environment and made his debut in New York on July 4, 1988.

A month later, his revamped “national” show debuted on 50 stations. Three months after that, his conservative political banter was heard on 50 more. In Rush’s wake, a new conservative talk format flourished, and he was soon joined by fellow travelers and imitators including Sean Hannity, Bill O’Reilly and Glenn Beck.

But as had happened time and again in its history, success on AM eventually led program hosts to seek greener pastures and ever more profits.

It didn’t take long for the new conservative talk to move to FM, satellite radio, streaming services and podcasting.

A Rural Stronghold

The one place AM radio still has a strong toe-hold in the media landscape is rural America.

A big reason for this is its longer transmission range, especially at night, added to the fact it is less impacted by physical barriers like structures or mountains.

As long ago as the late 1920s, it was this factor alone that made Nashville’s WSM radio a powerhouse and its “Grand Ole Opry,” a staple for a national audience, helping to popularize country music outside of the Deep South.

Today that reach is challenged by satellite radio, but AM radio continues to have a very distinct advantage in America’s heartland — it is hyper-local, where satellite radio is not.

In fact in many communities, small local AM stations have taken the place of local newspapers, providing loyal listeners with reliable access to local emergency information, weather alerts, agricultural news, and high school and regional college sports broadcasts.

Nearly 46 million people live in rural America, and recent studies, including a new one by Edison Research — which monitors Americans’ listening habits — suggest they do as much as half of the radio listening in their cars, trucks or other vehicles.

Which is why so many have been up-in-arms over recent decisions to remove AM radios from new electric vehicles.

To date, eight of the world’s top 20 automakers — including VW, BMW, Volvo, Mazda and Tesla — have already removed AM radio from their EVs because the new engines can interfere with the radio signal.

However one of the eight — the Ford Motor Company — has reversed course, with CEO Jim Farley announcing via social media that the company will keep AM radio on all 2024 Ford and Lincoln vehicles and it will use an online software update to restore it on two 2023 electric vehicles.

Farley’s move came on the heels of the introduction of the bipartisan AM for Every Vehicle Act.

The bill would:

- Direct the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration to issue a rule that requires automakers to maintain AM broadcast radio in their vehicles without a separate or additional payment, fee, or surcharge.

- Require any automaker that sells vehicles without access to AM broadcast radio before the effective date of the NHTSA rule to clearly disclose to consumers that the vehicle lacks access to AM broadcast radio.

- Direct the Government Accountability Office to study whether alternative communication systems could fully replicate the reach and effectiveness of AM broadcast radio for alerting the public to emergencies.

Proponents of the bill back it for a variety of reasons. Much of the support from Democrats appears to be based on public safety concerns; Republicans, meanwhile, also fear the demise of AM radio will spell the demise of conservative talk radio.

Since the bill was introduced, several former Federal Emergency Management Agency leaders joined in a letter calling on Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg to intervene on the grounds that eliminating AM radio receivers from vehicles poses “a grave threat” to disaster response relief efforts.

“The bottom line is AM radio is the backbone of America’s national public warning system,” said Gottheimer during a Zoom call with reporters.

“It’s how FEMA gets emergency alerts out to the public during natural disasters, extreme weather, health emergencies, and, of course, domestic terror threats,” he said. “Why? Because AM radio has already proven itself resilient in a number of different circumstances.

“Unfortunately, despite the clear public safety issues involved, many electric vehicle manufacturers apparently do not care,” Gottheimer continued. “They claim that the electromagnetic noise from their electric cars can disrupt the reception of AM signals. But that’s ridiculous because we know that the early Tesla’s had well-functioning AM radios.

“What’s really happening here is manufacturers are discontinuing AM radio in their vehicles because it costs a few bucks to add an adapter and make it work,” the congressman said. “Well, as I’ve said before, if Elon Musk has enough money to buy Twitter and send rockets into space, he can certainly afford to include an AM radio in a Tesla.”

Gottheimer said the other thing electric vehicle manufacturers have claimed is that AM radio “just isn’t relevant anymore.”

“That’s the furthest thing from the truth,” he said.

“The current data suggests that 47 million people are listening to AM radio every day, and you can imagine the huge economic impact that would occur if the automakers pulled the plug on that … it would have a seismic impact on the AM radio stations themselves, and also on their advertisers,” he continued.

Though he didn’t name his source, Gottheimer said there is also data that shows AM radio listenership is actually growing.

“So these decisions aren’t being driven by what consumers want,” he said. “It’s a question of these automakers trying to save a nickel, ignoring what the public wants and risking the security, frankly, of our country and our families.”

Picking up on the theme of AM radio’s continued relevance, Sen. Markey noted that many AM stations now cater to the nation’s immigrant communities, including 700 stations that broadcast in Spanish.

“This enables them to receive important information in their native languages, which again is critical to public safety and our economy,” he said.

Markey then turned philosophical.

“You know, radio has been under threat before,” he said. “Over 40 years ago there was a pop group called the Buggles who released a classic song called “Video Killed the Radio Star.” That song became iconic back in the days when MTV was supposed to spell the end of radio.

“Well, radio didn’t die 40 years ago, 30 years ago or 20 years ago. Like video before them, these automakers must and will fail in their effort to get rid of AM radio. That’s what’s going to happen when we get this legislation passed,” he said.

Dan can be reached at [email protected] and at https://twitter.com/DanMcCue