When Swing was King at the Embassy

WASHINGTON — As the son of a globetrotting diplomat, Ahmet Münir Ertegün had learned a thing or two about poise and sophistication by the age of 16.

But as members of Duke Ellington’s band assembled on the third floor of the Edward Hamlin Everett House, just off Dupont Circle, the teenager couldn’t help but feel his joy mix with apprehension.

The elegant building at 1606 23rd St., NW, was then the Turkish embassy and beginning in June 1934, Ahmet’s father, Mehmet Münir Ertegün, was Turkey’s ambassador to the United States.

By the time they arrived in Washington, both Ahmet and his older brother Nesühi were smitten with jazz and they soon began amassing a huge, and it would turn out, very valuable record collection.

Nesühi’s interest in traditional, New Orleans style jazz also inspired him to visit Washington’s Howard Theatre, on T Street NW, which played host to most of the great Black musical artists of the early and mid-twentieth century.

Nesuhi, no musical snob, soon fell in love with the more modern sounds of jazz contemporary Black musicians were playing.

And that led to the idea of inviting musicians up to the embassy to get to know them better and perhaps to hear them play exclusively.

“It really was Nesühi who set it up,” Ertegün said nearly 50 years later. “Duke Ellington and his band were playing at the Howard Theater and Nesühi went in and simply asked them if they wanted to come over for lunch the following Sunday.

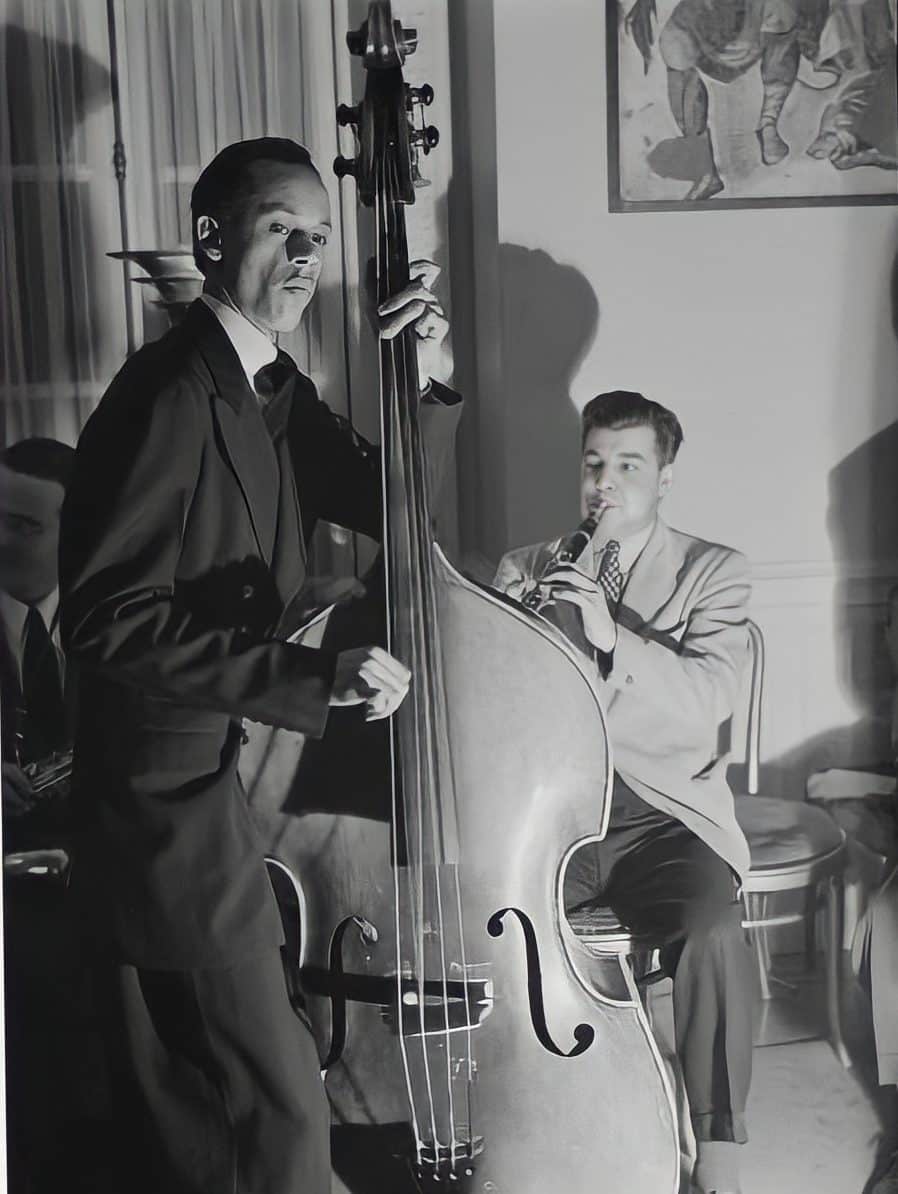

“At the same time, we had also struck up a friendship with Joseph Marsala, a terrific jazz clarinetist out of Chicago, and he was also in town with his band, so we invited them as well,” he continued. “That’s how the first terrific jam session at the embassy came to pass.”

Ertegün recounted all this in the early spring of 1988, just weeks before Atlantic Records, the legendary record label he founded, celebrated its 40th anniversary with a massive, 13-hour concert at Madison Square Garden in New York.

A Reporter’s Journey

A press ticket wasn’t difficult to procure, but landing interviews was another story. In the weeks leading up to the marathon concert, every music reporter in New York wanted a scoop — would the Rolling Stones be performing? (Answer: They did not.) And was it true the surviving members of Led Zeppelin would be reuniting for a one-off appearance? (This turned out to be true.)

Given the magnitude of the event, and the repetitive nature of the questions, it was largely decided that interviews and photo sessions and the like would be reserved for the “big” newspapers and magazines.

And yet, for one young reporter on Long Island — me — being left out was nothing short of galling.

While publications were giving me ample opportunity to write about contemporary recording artists, I had made it something of a personal specialty to search out musicians of the past and interview them.

In the days before the internet, I relied heavily on writing letters to local musician unions and time and again, I reached the person for whom I was looking, whether it was J.I. Allison, Buddy Holly’s drummer and co-writer of “That’ll Be The Day” and “Peggy Sue,” or blues great Willie Dixon, or the surviving members of Elvis Presley’s first band, Scotty Moore, D.J. Fontana and backing vocalists, the Jordanaires.

And only months before my pursuit of Ertegün I had secured an interview — over his initial reluctance — with Jerry Wexler, who had become a partner in Atlantic Records in the early 1950s and through his work with artists like Ray Charles, the Drifters, Aretha Franklin and others, helped to build it into a major force in the music industry.

Wexler was an “in,” I thought. But he proved to be a tenuous one in that I didn’t simply ask him to set me up. Instead, I brandished a copy of my Wexler interview, which had appeared in Goldmine magazine, as my calling card, and hoped for the best.

One afternoon, on my way home from an interview with an artist on another label, I stopped by Atlantic Records offices in midtown to plead my case.

Ertegün was in, I was told by an assistant, but he was with Mick Jagger at the time and couldn’t be disturbed.

“I can go grab some lunch and come back later,” I offered, but the assistant said no.

“I don’t know how long he’ll be,” she said. “Mick stopped by hoping to hear a song he’s interested in on the radio, but Scott Muni had played it just before he got here, so they’re waiting for Muni to feel enough time has gone by that he can play it again.”

“For Mick?” I smiled.

“Yeah, basically for Mick,” she laughed.

I left wondering how many people would ever suspect their favorite radio station was being programmed, at least for a few minutes, by the unseen hand of a Rolling Stone.

Still, I was no closer to getting even a few minutes with Ertegün. With the days ticking by, I wrote him a letter. After explaining who I was and what I wanted, I went on to say that a key element of most of my stories was how one got from “there to here.”

I was still just a kid, I said, trying to figure out the business and still felt stuck in a “here” that, to paraphrase Neil Young, everyone knew was nowhere.

The Ertegün Interview

It was the letter that did the trick, and just days later I was ushered into Ertegün’s office for a 15-minute interview that stretched on for nearly an hour.

Without much adieu, we were back in time, back at the Turkish Embassy.

Ertegün, an elegant man, explained he’d been born in Istanbul, Turkey, in July 1923, a few months before the founding of the Republic of Turkey. Mehmet Ertegün was initially named minister to Switzerland and Turkey’s representative at the League of Nations, and then quickly moved up the diplomatic ranks, being posted in Paris, London and finally, Washington, D.C.

“My mother was a very modern Turkish woman … who was interested in a lot of things and did a lot of things,” Ertegün said. “Her name was Hayrünnisa, and she liked to play cards and dance, and she was also an accomplished musician and a collector of popular records.

“And I believe she’s where our interest in music came from,” he said. “My father was a much more scholarly person and preferred to stay at home and read books, that kind of thing.”

By the early 1930s, Nesühi, who was six years older than Ahmet, already knew all about Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong.

In fact, before the family left London for the United States, Nesühi had seen both play at the city’s Palladium.

“Nesühi also subscribed to several French magazines that were full of these article about how wild and uninhibited this new Black American music was … and how jazz music was a new art form … so he was getting into that and, you know how you are at that age, you idolize your older brother and I became very involved in it as well.”

Because of their age difference, Nesühi did most of his concert attending on his own.

“He was allowed out at night,” Ahmet explained matter of factly. “But I did get to see and hear Cab Calloway and some others, right before I came to America.”

At the time, Mehmet Ertegün’s posting in the United States had temporarily fractured the family. He went ahead to Washington, while Ahmet and his mother followed a year later, and Nesühi, who was finishing school, came a year after that.

It’s likely that the few concerts he saw in London were a kind of solace. At the very least, the memories remained vivid decades later.

“I can’t explain how astounded I was to see these big beautiful big bands playing. You had these men in large formations …. These large bands with all these gleaming brass instruments. And they played the most powerful music that I ever imagined could exist.”

“Of course, I knew the songs from the records I’d hear, but to hear them in person for the first time, it was just an unbelievably exciting thing,” he said.

By the time Nesühi arrived in the states, Ahmet was actually attempting to compose his own songs and his mother had bought him a record-cutting machine so he could commit them to disc.

Once Nesühi arrived in Washington, he and Ahmet began making regular forays into the city’s Black district where they could see Ellington, Calloway, and others, including a very young Billie Holiday.

“It was the most natural thing in the world to go into a Black area in Washington, D.C., in those days, at least to us,” he said. “You have to understand, Turks had never been slaves and really hadn’t experienced the discrimination that Black people did in America.

“So there were things we didn’t see or understand right away. At the same time, Turks have long been regarded as enemies within Europe because of their Muslim beliefs, so we had some level of empathy,” Ahmet continued.

“So we never felt any hesitation about going any place in the city … and you know, I think you can go anywhere if you’re not looking for trouble yourself. You might have to swallow a few insults, here and there, but if you’re willing to take things with a grain of salt, you’re not going to have trouble.”

Collecting Treasures

More often than not, they prowled the city and the surrounding community in search of used records to buy, eventually assembling a collection of over 15,000 jazz and blues 78s.

“We went door-to-door, visiting the junkman and people like that … I don’t know what they thought of us, but they were certainly happy at the thought of there being somebody willing to pay for what they saw as some junk piling up in their basement,” Ertegün said.

“You know, these were old records by this point. Some hadn’t been played in years and years and never were going to be played again. And we’d pay them $4 or $5 dollars for 30 or more records,” he said.

Ertegün said his biggest find probably occurred in Annapolis, Maryland, when he got permission to explore the basement of a jukebox operator.

“I got down there and there were stacks of records everywhere, and amongst all this material I found an almost completely new Bessie Smith collection down there,” he said.

Suddenly Ertegün was in record collector mode, recalling how the original label looked on those records.

“As a collector you get interested in these kinds of things,” he said.

“But you know, that’s nonsense. It’s the music that is important. Still those original labels are eventually what made our collection very valuable,” he said.

Eventually, the war intervened and the government put out word that it needed shellac, the basis of records among other products, for the war effort.

“Who knows how many classic records were lost,” he said “Or how many wonderful collections? Suddenly, people were more concerned with selling their records by the pound.”

By this time, Nesühi and Ahmet Ertegün were old hands at hosting jam sessions at the Turkish embassy.

“I think the first one was in 1938 or 1939. And it was all very informal,” the younger Ertegün brother said. “We didn’t invite a bunch of people to come hear them. It was usually just my brother and I and my sister, maybe a cousin, and friends who would come to stay with us from Turkey or some of the other places we lived.

“And the invitation came with no strings attached. They were invited to come to the embassy to eat and drink and relax and occasionally they wouldn’t play a note, but that was very rare.

“What we found is that they really liked to play under the right circumstances, which typically was before a very small group of people who weren’t making a big deal of what was going on … if there had been 50 people around, intently watching them … well, in that case they would’ve been performing for no pay … and there was no reason for them to do that.”

Ertegün said most of the informal jam sessions occurred on the third floor of the Beaux-Arts style Edward Hamlin Everett House.

“That’s where our bedrooms were, and we had our own sitting room, and it’s also where we had all of our records. Nesühi and I had a room where all of our records were kept. So if there were very few people, we’d stay up there,” he said.

“If more people showed up, we’d move down to the drawing room, which was on the second floor. There was a library on the second floor and a large hall with a lot of sofas. And the ballroom on the second floor had a ping pong table and piano.

“About the only room we didn’t use was the formal salon … because it was just too uncomfortable,” he said.

Not everyone in the neighborhood was happy with the sudden uptick in traffic going in and out of the embassy Sunday afternoons. One neighbor, a southern congressman, is said to have complained vociferously about the Black musicians entering through the embassy’s front door.

‘Jazz Was Our Weapon for Social Action’

Ahmet Ertegün was just 17 when he presented his first actual concert in Washington, D.C. The first concert featured the great Sidney Bechet on soprano saxophone, Sidney De Paris on trumpet, Manzie Johnson on drums and Wellman Braud, one of the first members of Duke Ellington’s first band, on bass.

Among the other musicians who played that night were former Cab Calloway sideman Vic Dickenson on trombone, and Meade Lux Lewis on piano.

“Willie Bryant, a disc jockey known as the ‘Mayor of Harlem’ was the MC and we did this show at the Jewish Community Center in downtown Washington because it was the only hall we could get that would allow Black people and White people to mix together either in the audience or on the stage. No one else would allow it,” Ertegün said.

“A couple of years later, we did another jazz concert at the National Press Club auditorium, because they were also allowing for racial mixing,” he said. “You see, it started getting better over time.

“The war had started and Washington was becoming more cosmopolitan and less Southern as a city,” he said. “The National Press Club allowed us to have mixed Black and White people, both in the audience and on the stage.

As National Press Club Historian Gil Klein has written, the club’s membership was segregated at the time of the show — and would be until 1955. But the Ertegün brothers worked on the Club’s leadership until it relented to allow them to hold concerts in the auditorium — what is now called the ballroom.

“You can’t imagine how segregated Washington was at that time,” Nesühi told The Washington Post in 1979. “Blacks and Whites couldn’t sit together in most places. So we put on concerts … Jazz was our weapon for social action.”

“And for that second concert, the one at the Press Club, we had Teddy Wilson on piano, Zooty Singleton on drums, Lester Young on saxophone … we had Joe Marsala on clarinet … and I think we even had Lead Belly … so it was a really interesting line up,” he said.

In fact, Lead Belly, the folk and blues singer and musician, known for his impressive lung power and virtuosity on the 12-string guitar, was presented as a solo act by the brothers at the club. So too was Billie Holiday, the great Black jazz vocalist.

The brothers presented two more integrated jazz shows in the city, one at Turner’s Arena, an old boxing and wrestling venue located at 1342 W Street, and the last at the Uline Arena, at 1132, 3rd Street, Northeast.

The latter venue, renamed the Washington Coliseum, was the site of The Beatles concert in 1964.

The End of an Era

In June 1944, Ahmet Ertegün graduated from St. John’s College in Annapolis. Five months later, his father, the ambassador, died.

At the time of his father’s death, Ertegün was taking graduate courses in Medieval philosophy at Georgetown University.

“A lot of the people I went to school with felt they were going to be very importantly involved in government. Their vision from the moment they entered college was that they were going to graduate and go on to shape the future of the world,” he said.

“I didn’t feel that. I definitely didn’t relish the thought of going back to Turkey and eventually going into the diplomatic service, which seemed the direction things were heading in. I had seen that live. I had lived in embassies. There’s nothing wrong with it. But it wasn’t for me.”

The Ertegüns stayed in the embassy for several months.

Then, in 1946 President Harry Truman ordered the battleship USS Missouri to return the ambassador’s body to Turkey as a demonstration of friendship between the two countries and to counter the Soviet Union’s potential political demands on the Turkish regime.

Soon afterward, the rest of the family returned to Turkey while Ahmet and Nesühi stayed in the United States.

While Nesühi moved to Los Angeles, Ahmet stayed in Washington and decided to get into the record business as a temporary measure to help him through college.

“I think we stayed in the embassy for about eight months, and right before we moved out I had come to the decision that I needed to get rid of my record collection,” Ertegün said.

“It was too large to move anywhere and I really didn’t want to put it in storage. In a way, I guess, I realized I’d come to the end of an era and it was time to set off on my own, without any encumbrances,” he said.

Nesühi by this time had met and married Marili Morden, the owner of the Jazz Man Record Shop in Hollywood, California, a concern that specialized in traditional New Orleans jazz.

As a sideline, he also served as editor of Record Changer magazine.

“Record Changer had very little content aside from a column every issue by my brother and a few small reviews. Mostly it was a vehicle for trading and selling records, and that’s how I sold the collection we’d accumulated,” Ertegün said.

Proudly, the chairman of Atlantic Records noted “We got quite a lot for it … especially considering we’d really paid pennies for our finds, over a period of years.”

“The thing is, we had kept them in very good condition. We cleaned them. We played them only with very good needles. Each record was carefully cataloged. And basically what happened was we had several auctions over a period of a year or two … and we must have gotten $15,000 to $20,000 for the entire collection over that time,” he said.

Forming Atlantic Records

After splitting the proceeds with his brother, Ertegün now had enough money to begin considering forming a record label, but, he said, he still wasn’t completely convinced the record business was going to be his life’s work.

“I really wasn’t thinking that at all,” he said. “I didn’t have the confidence to believe it would work out successfully. And I thought maybe I could do it in a very limited way, putting out just a few records a year.”

“Really, it was just a stop gap, something to do while I was in school in Georgetown … until I got my degree and went back to Turkey,” he said.

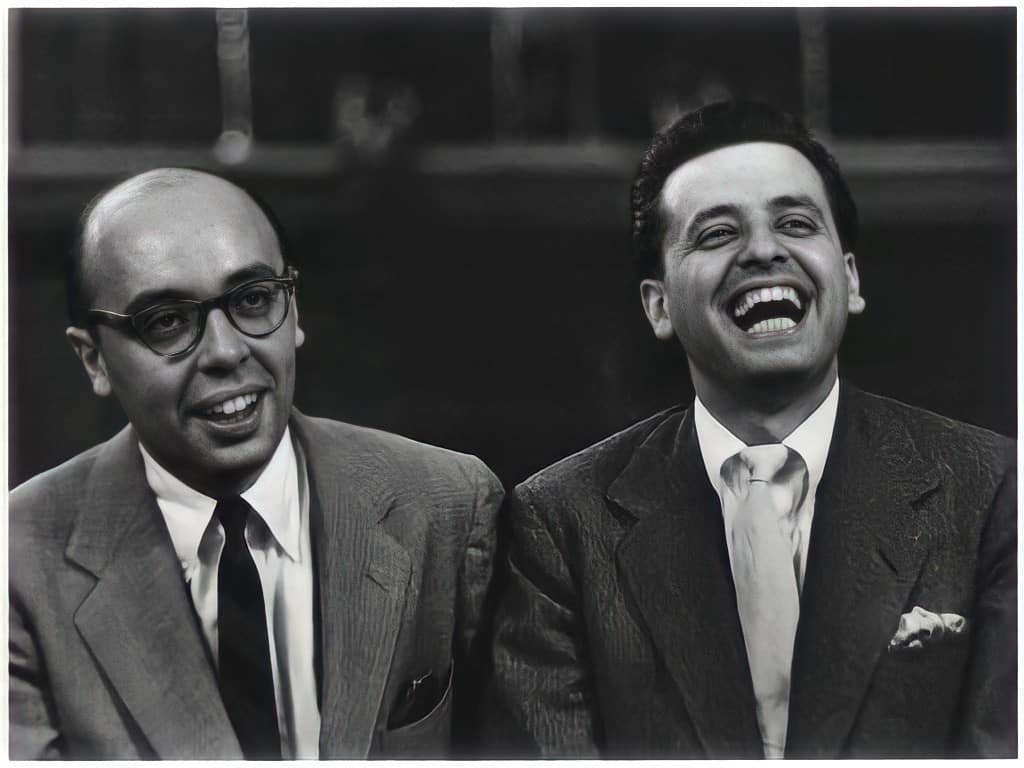

While Ertegün was mulling all this, he began to bounce ideas off a fellow student named Herb Abramson, a native New Yorker who was studying dentistry in Washington, D.C.

“We actually met when Nesühi and I were doing concerts. He was a fellow record collector and because he was living in New York at least part of the time, he would gather musicians for us up there, get them on the train and make sure they came down. He was our liaison man, so to speak.

“Later, while I’m thinking through what I want to do with the rest of my life, he leaves Washington and heads to New York where he enrolls in New York University and gets a job working for a company called National Records, as its A&R man.”

Abramson was lucky. Almost immediately, he found success making recordings with Billie Eckstein, a jazz and pop singer with a rich bass-baritone voice.

Soon, he was encouraging Ertegün to move to New York and try his hand at the business.

“In a word, I floundered,” Ertegün admitted.

“I knew something about the music part of it, but I didn’t really know anything about any other part of the record business,” he said.

Ertegün agreed to stay in New York, but only if Abramson, who had the experience and knew “how to get a record pressed and where to get a record pressed,” agreed to start a new label with him to record jazz, R&B and even some gospel music.

For financing, Ertegün turned to an old friend of the family in Washington, “My dentist, Dr. Vahdi Sabit.” With that, in September 1947, Atlantic Records was formed in New York City and the Washington chapter of Ertegün’s story was over.

The label released 22 unsuccessful records in a row, before it had its first major hit with Stick McGhee’s “Drinkin’ Wine Spo-Dee-O-Dee”.

With Jerry Wexler and later Nesühi Ertegün joining the label, Atlantic Records went on to be one of the major record industry successes of the 20th century.

Among its top-selling acts over the years were Ruth Brown, LaVern Baker, Big Joe Turner, The Clovers, The Drifters, The Coasters, Ray Charles, The Rascals, Vanilla Fudge, Crosby, Stills and Nash, Led Zeppelin, and through its 1960s era affiliation with Stax Records in Memphis, Ben E. King, Solomon Burke, Otis Redding, Sam and Dave, Percy Sledge, Aretha Franklin and Wilson Pickett.

An Editor’s Oversight

The irony of working so hard to secure the interview with Ertegün was much of it, including all of the above, never made it to print.

The editor with whom I was working asked only one question when I returned.

“Is Led Zeppelin getting back together?”

And when I said I didn’t even ask, he shrugged. “Well, at least you’ve got a ticket for a good show.”

The next and last time I saw Ertegün it was from a distance as he stood on the Madison Square Garden stage and explained that Atlantic Records was “all about making it all right for White kids to listen to Black music.”

Much of the crowd the night of the concert was indeed White, most were in their mid-20s or so, and as quickly became evidence, they’d coughed up a king’s ransom to yell their lungs out for bands like Yes, Genesis and yes, the newly reconstituted and sadly sloppy Led Zeppelin.

Throughout the long night, one historic performer after another took the stage, as did a number of newcomers.

For every Roberta Flack or Rufus Thomas or LaVern Baker, there was a very young Debbie Gibson or a Timbuk 3, all of them backed by an all-star outfit mainly comprised of the Blues Brothers Band under the direction of The David Letterman Show’s Paul Shaffer.

Iron Butterfly played an appropriately overly long “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida,” while Vanilla Fudge plodded out their set and the Young Rascals, Wilson Picket, and a stunning post-Disco Bee Gee’s stealing the show with a set comprised of some of their early pre-disco hits.

By the end of the night, the show had raised more than $10 million that was distributed to various charities including the Rhythm and Blues Foundation.

On Oct. 29, 2006, Ertegün tripped, striking his head on a concrete floor, at a Rolling Stones concert at the Beacon Theater in New York. He was immediately taken to hospital but fell into a coma and died on Dec. 14, 2006, at New York–Presbyterian Hospital-Weill Cornell Medical Center.

He was buried Dec. 18 in the Garden of Sufi Tekke, Özbekler Tekkesi in Sultantepe, Üsküdar, İstanbul, next to his brother, his father, and his sheik great-grandfather Şeyh İbrahim Edhem Efendi.

Dan can be reached at [email protected] and at https://twitter.com/DanMcCue