Looking Ahead to Hurricane Season …

Even if there’s only one named storm, if it hits your community, that’s a bad year

MIAMI — It happens every year, yet it never ceases to grab our attention, disrupt our sleep and on occasion even terrify.

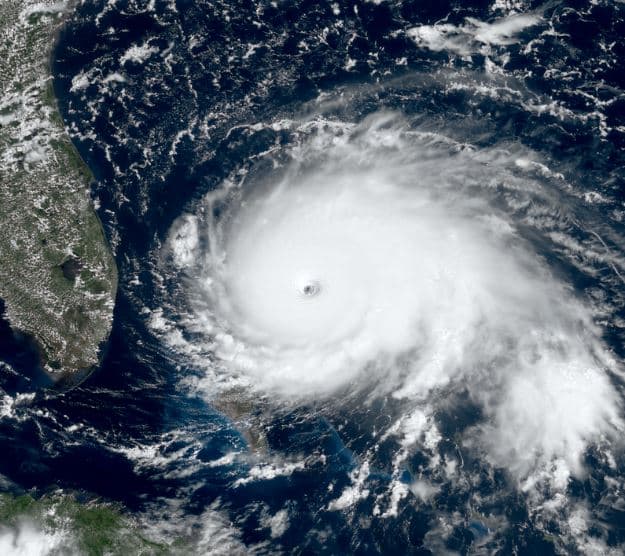

We’re talking, of course, about the Atlantic hurricane season, the period extending from June 1 to Nov. 30 when hurricanes are most likely to form in the Atlantic Ocean.

Though full-blown hurricanes are relatively rare in May and even June, it doesn’t take long for the number of hurricanes, tropical storms and tropical depressions that pose a threat to the U.S. mainland to increase considerably.

By mid-August each year, the Atlantic hurricane season has entered what might be called its prime time of activity, a period that, in climatological terms, peaks around Sept. 10, but can stretch well into October.

The National Hurricane Centers’ annual hurricane season forecast won’t be released until May 24, but on average, 10 named storms occur each season, with six, on average, becoming hurricanes and 2.5 becoming major hurricanes with winds of 111 mph or greater.

The most active season on record was 2020, during which 30 named tropical cyclones formed. Despite this, the 2005 season had more hurricanes, developing a record of 15 such storms.

The least active season on record was 1914, with only one known tropical cyclone developing during that year.

On Tuesday, The Well News caught up with National Hurricane Center Director Ken Graham while he attended the Governor’s Hurricane Conference in West Palm Beach, Florida.

This year’s installment of the annual event, considered the most comprehensive and largest hurricane conference in the nation, is the first to be held live and in-person since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic.

The weeklong conference includes more than 40 training sessions and 50 workshops for emergency management personnel, hurricane specialists and meteorologists.

Graham began his career with NOAA in 1994 as an intern forecaster at the National Weather Service in New Orleans, Louisiana. His career took him to agency’s Southern Region Headquarters in Fort Worth, Texas, as the marine and public program manager during National Weather Service

Modernization in the early 1990s.

He became the meteorologist-in-charge at NWS forecast offices in Corpus Christi, Texas, and Birmingham, Alabama, where the office was awarded the Department of Commerce medal each year (2001-2005) for innovative services, such as instant messaging with television stations during critical events such as the Veterans Day tornado outbreak in 2002.

He has also served as systems operations chief at Southern Region Headquarters where he won a Bronze Medal for leading a team to make critical repairs in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina.

Graham received the National Weather Museum’s Weather Hero Award for 2010. He was a finalist for the 2021 Service to America Award and, in 2022, was recognized by the Federal Alliance for Safe Homes as its Weather Person of the Year.

TWN: Director, thank you for giving us a little bit of your time during what I’m sure is a very busy event …

KG: Well, thank you for helping us get the word out.

TWN: Many years ago I spent some time down at the hurricane center with one of your predecessors as director, Max Mayfield, so this is kind of a long-awaited follow-up for me …

KG: [Laughs] Max is great. I still talk to Max on a frequent basis.

TWN: So let’s talk about the present. You’re now attending the Governor’s Hurricane Conference down in West Palm Beach, Florida. How is it going? And more importantly, what are you hearing? What’s been noteworthy, two days into the event?

KG: I think the biggest thing, so far, is that we’re back together. I think about 2,100 people registered for the conference, and if you think about this business that we’re in — dealing with disasters — the more you know and understand each other, the better your response is going to be during a disaster.

This is the first time we’ve gotten together since 2018, and the biggest thing I’ve been hearing is, ‘We’re happy to be back. We’re ready to learn. And we’re ready to get ready for the next hurricane season.‘

TWN: Now, you mentioned the pandemic. It obviously kept people apart, did it have any other impact, perhaps slowing the learning curve about the danger of hurricanes and hurricane preparation?

KG: Well, we did the best we could and we turned everything to virtual. So we still did our training classes, both domestically and internationally. It was just we did them virtually, and I think that worked out fine.

We even created a program to work specifically with teachers and students to get everybody ready as best we could. But like I said, there’s just something about being together. There’s something about knowing each other ahead of time. I mean, you can get training done remotely, but you can’t do a handshake virtually. And having that relationship and trust can never be underestimated in a disaster.

TWN: Has anything changed in terms of how people plan their emergency response since the onset of the pandemic?

KG: In terms of emergency response, those decisions, on evacuations and such, are made on the state and local level. But what we did was, we doubled down on the science. We doubled down on the information we could provide when it comes to storm surge forecasting and really trying to pinpoint exactly where those danger areas are.

You know, we always talk about evacuations, but we don’t have any conversations about the importance of not evacuating an area that doesn’t have to evacuate. Because evacuations are, in and of themselves, dangerous. People can lose their lives in an evacuation.

So we doubled down on really trying to pinpoint where the most dangerous areas were when it came to storm surges to ensure that we [were] recommending evacuations to only the most potentially affected areas.

Also, when you evacuate too broad an area, you increase the chances of people saying, “Well, nothing happened, so I may not go next time,” when they really need to.

So in terms of what I really wanted to speak to at this conference, it’s that we’ve really been working on the storm surge forecast science to make emergency management decisions more effective.

TWN: Now that’s a very interesting point to me because I can remember what happened when Hurricane Floyd was approaching the east coast of Florida in the early autumn of 1999. It was a monster storm, one that would eventually cause over $6.5 billion in damages. And it also, based on reporting since then, triggered the fourth largest evacuation in U.S. history. But Floyd ultimately turned away from Florida, and many of the evacuees, who’d high-tailed it to North Carolina, in particular, found themselves in the real path of the storm …

KG: Okay, so let’s go back to 1999. You mentioned Floyd. Back then, we didn’t have as much confidence in the forecast as we do today; our margin of error was just so much greater then. Now, our 24-hour error in the forecast track is about 30 miles.

We’ve made incredible improvements in the forecast track and also in the intensity as well. Look at the last three years. We’ve cut the intensity forecast error in half, so we’re making the forecast so much better. If you look at Floyd, in 1999, which caused one of the largest evacuations in U.S. history, and you compare that to Hurricane Dorian in 2019, where you had somewhere around 3 million people who did not have to evacuate, you can see how far we’ve come in forecast confidence.

Similarly huge storms followed similar paths, but when you can pinpoint specific areas on the coast where you’re going to see the storm surge or maybe where high winds are going to make a bridge impassable after a certain time, you can target your emergency response. And as a result, you warn the people who need to be warned and we don’t have to evacuate as many people. And that’s just good all the way around.

TWN: Okay, so how does this square with people who will say, “But I’ve heard that with climate change these storms are getting bigger and stronger. Wouldn’t it follow that we have to evacuate larger areas?”

KG: It’s still all about the impact. You can’t really go by the increasing number of storms that we’re seeing because the reality is, we’re naming more storms because we have better tools with which to recognize them. We’re seeing more satellite imagery, we’re getting more data from hurricane reconnaissance and hurricane hunters.

And you can’t go by the increased number of strong storms that we’re seeing, based on recent trends. In the end, in terms of the forecast and in terms of dealing with these storms, it’s still all about the impact.

It’s all about how much rain is going to fall in a specific area, what’s the wind going to be, how much storm surge are we going to get. Regardless of climate change, it’s still all about the impact. And it’s all about timelines. And if you look at the last 100 years, every storm that has hit this country with winds of 150 miles per hour or greater was a tropical storm or less three days out. So it’s about being prepared, because they don’t have the lead time that we’d like in advance of some of the greatest storms that hit this country.

TWN: Well, that was certainly the case with Hurricane Andrew, which devastated the Miami, Florida, area in 1992, and I can personally remember when Hurricane Katrina crossed over South Florida and moved into the Gulf, before raining destruction down on New Orleans, Louisiana, and the Gulf Coast. I mean, one person died in the Miami area when Katrina came through, but it was relatively tame by hurricane standards at that point.

But let me ask you this. People are always watching the cone of probability. When a storm is in the area, people turn on the local news or The Weather Channel and obsess over the cone. Are you saying that as a result of improvements in the forecast, that the cone is now going to be skinnier and skinnier?

KG: The better we do, the smaller the cone. Because actually, the cone is where we think the center of the storm is going to be two-thirds of the time. Anywhere in there. And that also means the center of the storm could be outside the cone as much as two-thirds of the time, because of error, and that does happen.

So, the better we do, the smaller the cone, which is a good thing. However, now we have to involve social science more because now you have more impact outside that cone. With a skinnier cone denoting the center of the storm, you can still see heavy rainfall 100 miles, 200 miles outside, in one of those rain bands outside that cone. You can see storm surge well outside the center. So now we have to communicate.

So it’s not just about the cone. It’s about the uncertainty. It’s about looking at a situation 24 hours out and thinking the center of this storm could be 30 miles, plus or minus from this area, forward or backward, to the left or to the right. All of that is a good forecast 24 hours out, but that distance of 30 miles really does alter the impact on the ground. Little wiggles in a hurricane’s path really do matter.

TWN: Let me ask you another question I’m basing on perception. We all saw the devastation Hurricane Sandy brought to the New York/New Jersey area in 2012. And it seems during the past few years that a growing number of storms are forecast to strike the Northeast and New England with a lot of punch. Is this a byproduct of climate change? Are these storms actually having more of an impact further up the Atlantic coast than they used to?

KG: You could go back in history and see some large storms that hit the Northeast, but I think if you look at the research what you’ll see is some heavier rainfall in some areas than you’ve seen in the past, and you’ll see that some of the events we’ve witnessed have been slower systems that simply had more time to cause more rainfall and push storm surge into certain areas.

But I think the factor that is really important to be mindful of is, the moisture from these storms has got to go somewhere. Even in the case of a Gulf storm. If you go back to Camille in 1969, there were actually more fatalities inland from Category 5 Camille that hit the Mississippi coast. There were fatalities in places like Virginia from the heavy rainfall and the mudslides. And if you look at Hurricane Ida in 2021, you see a very similar trend.

In the case of Ida, you had a strong Category 4 hurricane hit the Louisiana coast, but you had more direct fatalities in the Northeast from the storm than you had on the Gulf Coast.

So I think the thing to remember here is that the moisture had to go somewhere, that the wind is going to have a significant impact, even well after landfall — and this applies to inland as well as on the coast. So you’ve got to be prepared for these big systems.

TWN: That said, is the nature of preparing for a major hurricane different in the mid-Atlantic or Northeast, compared to a place like Florida? I mean, the soil is different. The trees are different. Even the building construction is different.

KG: Every place is different. Think about the storm surge in Louisiana versus the east coast of Florida. Louisiana is more similar in some ways to parts of the mid-Atlantic and parts of the Carolinas where you can get this storm surge that stretches inland for miles.

So the preparedness is a little different, the evacuations can be a little different. But in the end, if you are preparing for the impact of storm surge, the preparation is going to be about the same. It’s just the location changes.

But what we have to keep talking to people about is inland rain. Since 2017 we’ve had more fatalities associated with inland rain than we have from storm surge. Ninety percent of all fatalities associated with these storms are water-related. And yet when people close their eyes and imagine these storms, most envision the wind and the impact of the wind. So we have to have more conversations about the dangers of the water — a full 50% of inland fatalities associated with these storms come from water. Many of them occur as a direct result of people driving their automobiles into water during and after a storm. So we’ve got to keep talking about this and getting that messaging out. … And that’s why we’re so serious about involving social science in everything that we do.

TWN: Before I let you go. Everyone has heard of the National Hurricane Center, but few people will ever go there. Can you tell our readers a little bit about what it’s like, how many forecasters you employ, and so on?

KG: Well, I think the first thing that would surprise people is we’re not as big as people think. We have nine hurricane specialists, and a 10th, who works for the Navy. During the offseason we’re getting everybody prepared by doing exercises, we’re doing training, getting ourselves ready.

And then during the season, we’re basically on call, ready to go. And if there’s just one storm out there, it’s one thing, but if you’re dealing with four storms at the same time — which happens quite often — that’s all hands on deck.

But it’s not just the hurricane specialists. A part of the National Hurricane Center that most people don’t get to see is the whole team of forecasters we have in the tropical analysis forecast branch. Twenty-four hours a day, all year, they’re actually issuing marine forecasts for the Atlantic and the Pacific, a big chunk of those oceans, and also for the Gulf of Mexico, keeping ships safe and keeping everybody safe on the seas.

TWN: I know the center’s forecast for the upcoming hurricane season doesn’t come out until May 24, but do you have any last words of advice for people that want to get ready now for what’s ahead this summer and next fall?

KG: All indications are that the models are pointing to another La Nina season, which means it’s probably going to be another busy season.

My advice, independent of the seasonal forecast, is this: If there’s one severe storm on Earth and it hits you, it was a busy hurricane season. So you have to be ready, every single year, as if you’re going to be hit. Little wiggles in the forecast track matter. Just because it didn’t happen last time, doesn’t mean it won’t happen this time. So it’s all about knowing your risk and being ready.

Dan can be reached at [email protected] and @DanMcCue