Dwight Chapin, the ‘President’s Man,’ Talks Nixon, Ukraine and More

WASHINGTON — One of my late mother’s favorite stories of my childhood involved my first “vote” in a federal election.

It was the fall of 1968 and I was in kindergarten and our teacher, Mrs. Blumberger, decided that in addition to our stacking blocks and learning our upper- and lower-case letters, we would all participate in an in-class election.

Our “voting booth” was fashioned from a rectangular cardboard box with one side removed and on the inside of the other were two pictures, one of former Vice President Richard Nixon and the other, incumbent Vice President Hubert Humphrey.

Below each picture was the candidate’s last name.

History did not make note of the outcome of the 1968 presidential election in Mrs. Blumberger’s class at Northedge Elementary School in Bethpage, New York, but one has to assume it ended in a landslide for Humphrey.

I assume this because I was the only student whose parents were called to the class the next day to talk about what I’d done.

I’d voted for Nixon. And the powers that be in my young school life wanted to know why.

“Because he looked like a president,” I said, no doubt shrugging and in no way understanding what the hubbub was about.

My mother always laughed at that last line of the story. On the phone from his home in Riverside, Connecticut, recently, Dwight Chapin, the one-time appointments secretary and deputy assistant to President Nixon, did the same.

“Oh my God …” he said to the sounds of the kind of hearty laugh that suggests throwing one’s head back and letting it rip.

“And you were … in that much trouble at that age …” he said. “Oh, wow.”

This coming June 17 will mark the 50th anniversary of the break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate Office Building in Washington, D.C.

The bungled burglary shortly after 2 a.m. on June 17, 1972, an attempt by the Nixon re-election campaign to wiretap phones and steal documents — marked the start of the “Watergate scandal” that would drive Nixon from office two years later.

Four months before Nixon’s resignation from office on Aug. 9, 1974, Chapin became the first person to go on trial and be convicted, despite protesting his innocence, in the wake of the scandal.

After a trial before U.S. District Judge Gerhard Gesell, Chapin was convicted of deliberately lying twice to a federal grand jury about his connection to political saboteur Donald Segretti.

Specifically, he was found guilty of directing a political “dirty tricks” operation against the presidential primary campaign of Sen. Edmund Muskie, D-Maine, and knowing that Segretti distributed fake campaign literature.

The convictions landed him nine months in the minimum security lockup in Lompoc, California. Chapin was acquitted of a third charge of lying to a grand jury when he denied telling Segretti to avoid talking to the FBI about his activities.

A half century later, Chapin, now 81, bears Richard Nixon no ill will over Watergate or his incarceration.

In fact, if there’s one consistent theme that runs through Chapin’s new memoir, “The President’s Man,” it’s that we would all do well to remember Nixon not as a disgraced president, but rather as a patriot and a brilliant if flawed public servant who was often misunderstood in his time and continues to be today.

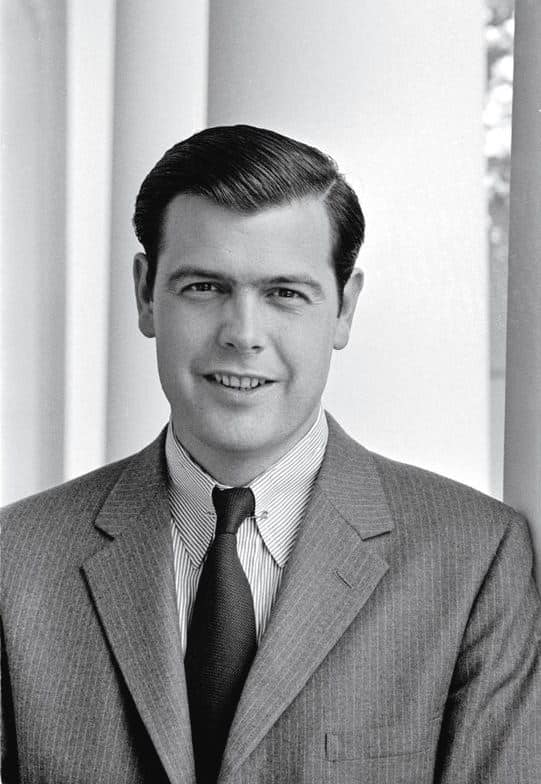

The interview that follows begins with Chapin, then a 21-year-old college student, meeting Nixon in 1962.

Nixon was just two years removed from his narrow defeat by President John F. Kennedy two years earlier, and was running for governor of California. Chapin was a field organizer for the campaign, but the two had never crossed paths.

Just six years later he’d be serving a far bigger role in Nixon’s successful bid for the presidency and ultimately serve as chief of protocol when, in February 1972, Nixon became the first U.S. president to visit communist China.

TWN: Tell me about the first time you stood face to face with Richard Nixon.

DC: Well, I had been hired to be a field man for the 1962 gubernatorial campaign. At this point, Nixon had lost to Jack Kennedy in the 1960 presidential campaign, and Nixon was running against Pat Brown for the governorship in California … just trying to keep his political life ticking.

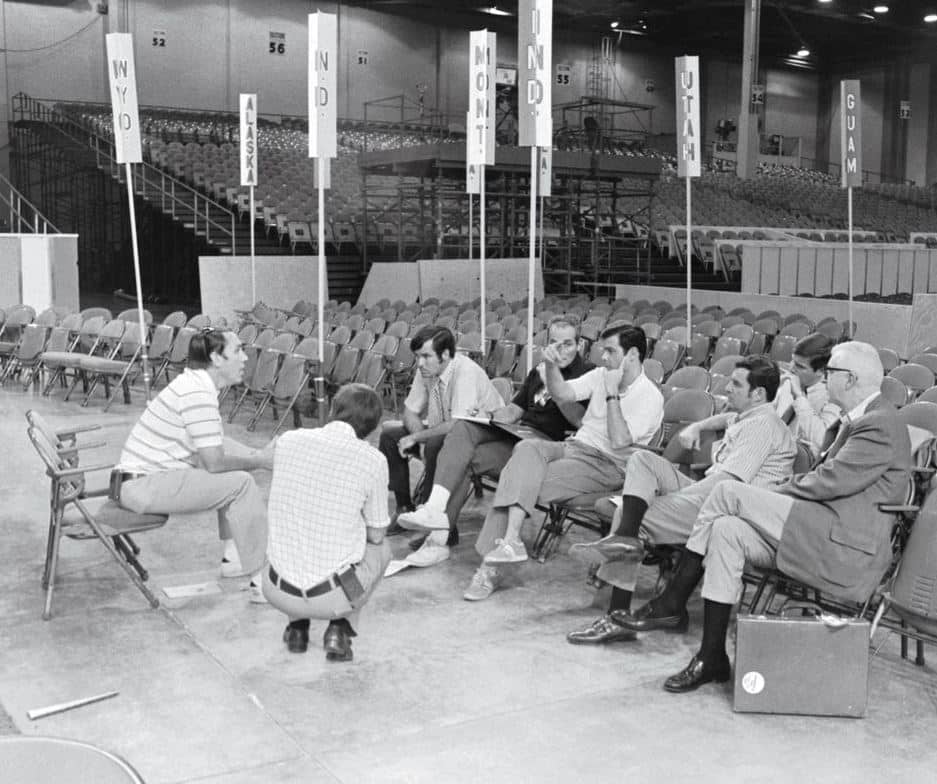

So they had sent a note to all of us who were field men to be in the headquarters on whatever the given date was because the candidate wanted to meet us and talk with us. Of course, we all showed up on the given date, there were probably eight of us, all pretty young. I was 21 and a student at the University of Southern California, but I was on Nixon’s paid staff.

So we’re all standing around and all of a sudden, in he comes. By then, of course, he’d been a congressman, a senator, vice president for eight years … so he had this mystique about him. I mean, you knew or felt that there was something very special about this man.

He went around, shook each of our hands. He asked where we were from in California, where we were going to school, what kinds of things we were interested in … and then, zip zap, 10 minutes later, he was gone. I mean, it was a very quick introduction.

TWN: We talk a lot these days about the state of the Republican party and about the influence of Donald Trump and so on. What was the Republican party like in those days, particularly in California?

DC: During the primary, Nixon was running against a conservative by the name of Joe Shell. He had been a successful independent oil man and everybody thought Joe Shell was going to be the candidate to run against Pat Brown.

That is, until Nixon stuck his nose in at the end of the campaign and took on Joe Shell. And that became a very dicey issue because Nixon was viewed as more of a middle-of-the-road, pragmatic Republican than Joe Shell was …. And sure enough, the minute Nixon entered the fray, Joe Shell moved further to the right.

Of course, Nixon beat Shell in the primary because he was both better known and had the stature of having been vice president, and that really upset the conservatives.

One of the interesting facts about Nixon’s career is that two years later, when [Arizona Sen.] Barry Goldwater got the [presidential] nomination, nobody worked harder for him than Nixon did. In fact, the joke at the time was that Nixon worked harder for Barry Goldwater than Barry Goldwater did.

What was behind it all was that Nixon had taken on Joe Shell in the earlier gubernatorial primary and was trying to repair fences with the more conservative wing of the party. That was going to be vital as he looked forward six years to the presidential race in 1968.

TWN: That raises an interesting question. People who remember or who have read about Nixon over the years know that in 1962, after his loss in the governor’s race, he pretty much lashed out at the media during a press conference at the Beverly Hilton Hotel, famously saying “You won’t have Nixon to kick around any more, because, gentlemen, this is my last press conference.”

So, my question is, did you know that morning that somewhere in the back of his mind he was already doing the calculus for a run for the White House? Did you know, in fact, that you had a future tied to such a run?

DC: No. Not at all. I was there that morning. I was standing probably 14 feet away from him when he made that famous speech … and at the time, I think everybody thought it was curtains.

Shortly thereafter, in December 1962, I was hired by Bob Haldeman, who was later to become chief of staff for Nixon, to work for him at the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency.

Once I got over there, Bob and I would have lunch or talk periodically, and I discovered fairly soon thereafter that Nixon was going to move back to New York and he was going to start plotting his course to become president.

Then Kennedy got assassinated and Nixon made the critical decision not to take on Lyndon Johnson in 1964. He decided, as I said, that he would campaign his tail off for Barry Goldwater in 1964, and he would wait until 1968.

So the political calculations really clicked in during 1963, when Nixon got back to New York and started figuring out how he was going to make a comeback.

TWN: Let’s talk a little bit about your political education. You started out being a field man for Nixon in California. What exactly does that mean?

DC: I was in charge of Ventura County, Santa Barbara County and the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles County. The San Fernando Valley is a huge area. Back in those days we would establish local campaign headquarters and staff them with women volunteers and they would work the precinct sheets.

Everything I was involved in was strictly grassroots. And I mean, it was very elementary and very grassroots. We would go through the precinct sheets and send people out to knock on doors, talking to people about voting. And then it entailed figuring out who our voters were and how to get them out on Election Day.

So at the outset, in that 1962 campaign, I was Mr. Grassroots.

TWN: OK, what are you doing, say, post-1964? Are you boning up on national politics or doing other things so that you’ll be ready for a campaign when he is ready to run?

DC: Well, what happened was, I was transferred from the Los Angeles office of J. Walter Thompson to the New York office, so that I could learn more about advertising and so forth.

And it was Bob Haldeman who suggested I call Rosemary Woods, Nixon’s secretary, and let them know that I was in New York and available for volunteer work or to help out however I could.

Well, they were happy to have me. And what happened was, I was working in midtown Manhattan during the day and then I would go down to Wall Street, to the offices of Nixon’s law firm, Nixon, Mudge, Rose, Guthrie & Alexander, after my regular work hours and put in three or four hours a night, answering his mail.

Now, at this point, Nixon’s is a very popular figure. He’s getting hundreds and hundreds of letters a week, and many people want him to run for president.

Now, the key thing here is the person teaching me how to answer all that mail was Mrs. Nixon herself. Mrs. Nixon is teaching me the ropes. And that led to her getting to know me and getting to know about my family — by this time I was married and had two little girls. And over time, she begins to trust me. Because, you know, when you’re working for a family in an “inside” type of situation like that, trust is everything.

So I’m sure what happened is, she mentioned me to the former vice president and told him how I was working my tail off, going down there in my free time to do these letters, and that led to my being invited to be his personal aide.

So to answer your questions, between 1965 and 1967, I’m just doing this volunteer work and helping out — I did some advance work, also — and then I joined the staff full time in 1967.

TWN: The following year, of course, is an election year. The election year, as far as Nixon is concerned. But it’s also a year of turmoil. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is killed in Memphis. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy is murdered in Los Angeles. Then there are the riots … and the mayhem outside the Democratic National Committee in Chicago. Your thoughts on that year?

DC: You thought the country was falling apart. And it was not unlike what we witnessed a couple of summers ago with all the riots after the death of George Floyd, where you had riots and demonstrations spread to several cities.

So we have the assassination of Martin Luther King, and the assassination of Bobby Kennedy, as we have Johnson deciding not to run, and we have fires and demonstrations in major cities — plus you still have the Vietnam War going on and all the heaviness associated with that. It was a really, really rough time.

And the answer to your question is, we were handling it all day by day. I mean, the landscape just kept shifting.

And the thing about President Nixon, or at that time, candidate Nixon was that he was very good strategically. He was very good at figuring out the lay of the land and how it affected his campaign if the cards got shuffled. He was brilliant — I’d say very brilliant in terms of strategy and the management of his campaign, in knowing what alterations or changes to make in terms of rapidly changing circumstances.

TWN: How would you compare the presidential campaign operation to the one you were involved in in California? Was the difference solely one of an order of magnitude?

DC: Well, our campaign manager was John Mitchell, who later became attorney general, and he had been a law partner of President Nixon’s.

One thing he did was go to all of the states that had Republican governors and put together an apparatus that utilized the organizations those governors had and gave them responsibilities for delivering those states.

We did have area managers, people who were looking after various geographical parts of the country, and many of those people had run similar operations during the Goldwater campaign. They had experience from being involved in the most recent presidential contest and Nixon brought them into the fold and used them again.

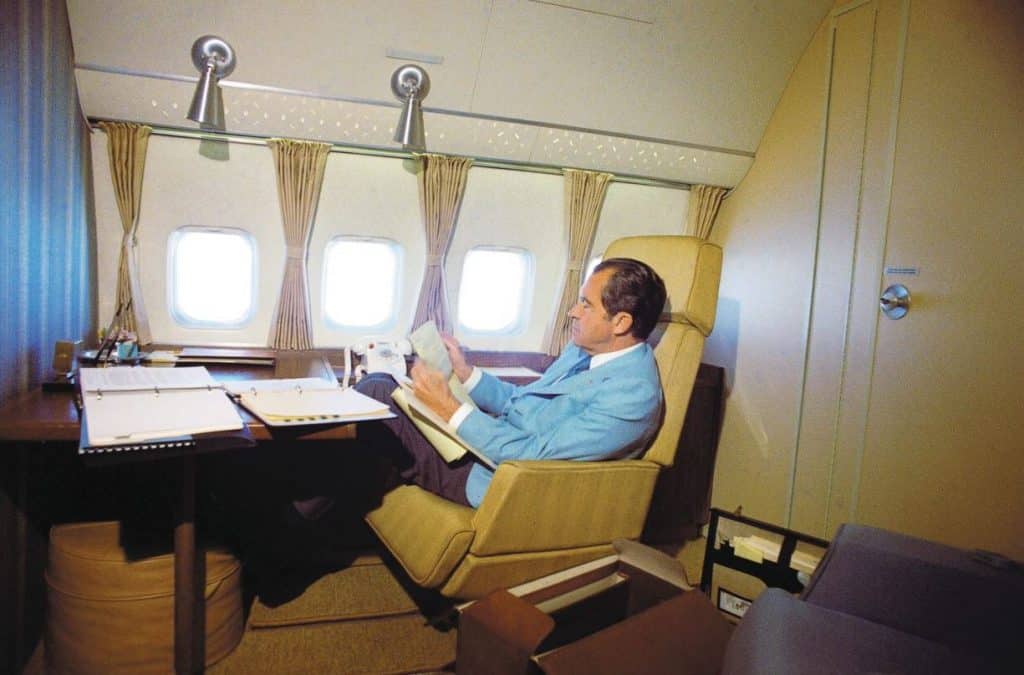

I can’t speak to the grassroots part of it because once the 1968 campaign got underway, I was on the airplane with him, traveling everywhere he went, and I was completely out of the grassroots business. I was watching this highly efficient machine from the perspective of being at his side.

TWN: Now, the impression we get of Nixon from books and movies is that he was kind of an awkward guy around people. And yet, he successfully ran for president twice. So how much of this alleged awkwardness is a myth?

DC: Well, some of it is a myth, though he was more of an introvert than an extrovert. And in that way I think he broke what we might consider the political norm.

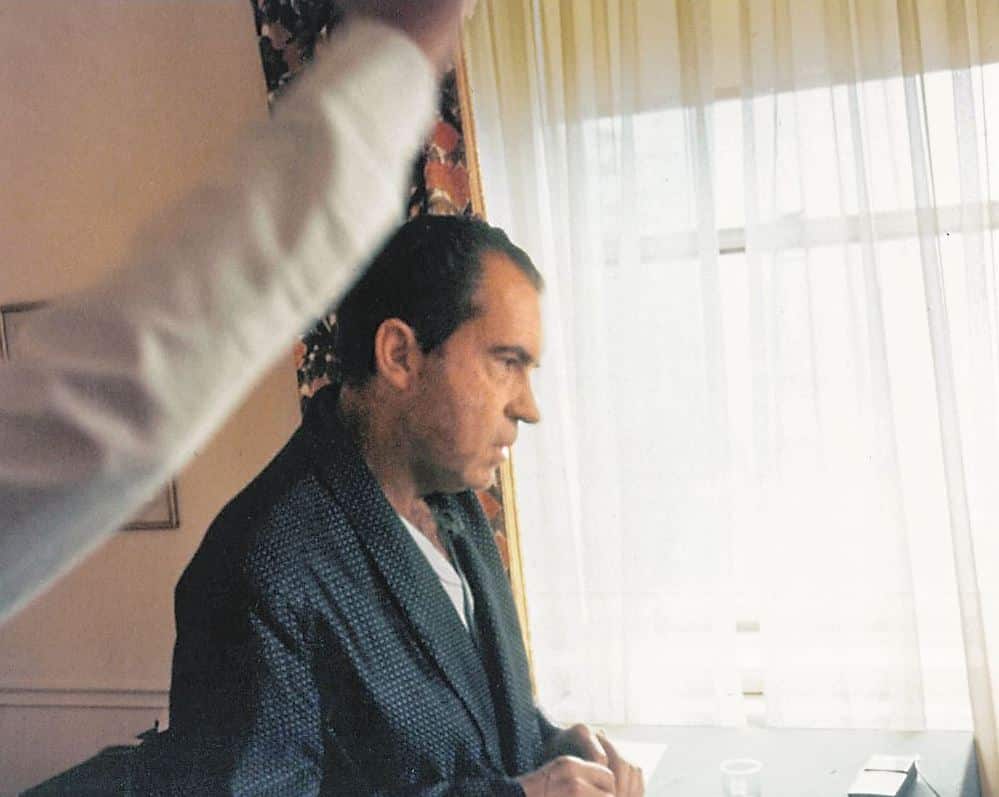

But after saying that I have to add that he delighted in writing and working on his speeches.

He would use a yellow pad, he’d sit in a hotel room or the back of the car, wherever we were and he’d go through them.

So even though he might simply be delivering a stump speech, he always had pieces of new material that he had written or that his speech writers had given him and he had edited, that he would add.

He enjoyed the process of working with the words and then communicating those words to an audience to see what worked and what didn’t work. He was very good at the oratorical skill of campaigning. If you ever listen to some of his campaign speeches, you’ll find that they were excellent. They were in their own way works of art. People remember JFK for “Ask not what your country can do for you …” but people really never focused on how good Nixon really was as an orator. He had been a debater in college. And he understood the art form of moving an audience with his words.

TWN: Why do you think Nixon is underappreciated in this way? Why is Kennedy rated so highly, but Nixon not?

DC: Well, not to be blunt about it, but Kennedy got shot and killed. He was assassinated. And then the Camelot myth grew up around him disproportionately to anything else we had witnessed in the political realm.

I mean, looking back at that period of time, late 1963, Kennedy was in serious political trouble. That’s one of the reasons he went to Dallas. But of course, once the assassination happened, all that disappeared. And Nixon, I think, suffers from being caught in contrast to the image-making that followed the assassination, because Nixon was the opposition. And, frankly, he was viewed in a secondary role until he made his political comeback.

TWN: Okay, so Nixon is elected president. He’s in office, the war in Vietnam is still raging, protests continue, including the massive Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam demonstrations in the fall of 1969, yet at the same time, the Nixon administration is firing on all cylinders. He signs a nuclear missile treaty with Russia, he eventually visits communist China, he creates the EPA and signs the Clean War Act into law and so on. What was it like to be in the White House during those times?

DC: It was amazing to be there. And I give tremendous credit in my book, “The President’s Man,” to Bob Haldeman, who put together a system, a staff secretary system, as a way of managing the White House and also managing the president.

I’ve spoken to seven White House chiefs of staff since then, in succeeding administrations, and they all complement the Nixon administration and particularly Bob Haldeman on how he got the organization in place and how it functioned.

On a day to day basis, we were all working our tails off, the president being probably the hardest worker of all, and we were so busy, so entwined in the work of government and working on these policy issues that he wanted to pursue, that we never really had time to ask ourselves, ‘Is this fun or not?’ It was also just … unfolding.

TWN: What was the thing that surprised you the most about Richard Nixon?

DC: Well, of course, in terms of a historical event, the biggest surprise was his decision to go to the People’s Republic of China in February 1972. And we know that from the reaction at the time. Most of the nation was startled by this move.

But it is interesting you mention surprises because I would, as someone who was a personal aide to Nixon, if someone came to me and said, what’s the most important thing to put in a manual on how to work with Richard Nixon, I’d say, “eliminate all surprises.”

He liked consistency and doing whatever it took to maintain a stable environment. We were talking a moment ago about campaigning. Well, he liked to keep the campaign working in a very well organized, methodical way. I mean, we weren’t big on letting him run three or four hours behind schedule, like some candidates do; we were known for being more like a Swiss watch.

Our operation functioned in a very methodical, organized way. That was one of the keys to our successes. And it definitely was one of the keys to the management of Richard Nixon.

The other point I want to make is people forget that Nixon had a Democratic Senate and a Democratic House that he had to deal with. The other day I was looking at the films from the China trip and one shows Nixon, on the South Lawn of the White House, getting ready to leave for China.

And he steps up to the microphone and the first thing he says is, “I want to thank Majority Leader Mike Mansfield, D-Mont., and Speaker Carl Albert, D-Okla., for being here today with the other leaders of the bipartisan Congress.” And he gives credit right there.

And I thought to myself, I was in charge of the schedule and I can tell you that every week the bipartisan leaders of Congress came down to the White House and met with Richard Nixon in the White House and they talked about policy and legislation.

In today’s world, if members of the political opposition come to the White House and meet with the president, it’s national news. Back then, it was a weekly event. And that’s why so much got done.

TWN: Why was bipartisanship important to Richard Nixon?

DC: I think because Richard Nixon had come out of Congress himself, because he’d been in both the House and the Senate, and because he’d worked with Congress through the whole time that he was vice president, he understood that if he was going to get any of his legislation through, it was going to be with the support of the Democratic House and the Senate.

The other thing is, because of the experience I just mentioned, he knew many of the senators and representatives personally — even members of what you might call the opposition. They were friends and they would come over and have cocktails at 5 o’clock in the evening and they’d communicate with one another.

Now, there were times when they didn’t all come, when it was Nixon and some of his select friends, but he knew he had to get along with these people. And that you had to be willing to compromise on legislation so that they could get it through through the Congress.

TWN: Did he get any blowback on this from diehard Republicans?

DC: No he didn’t. He would meet with the bipartisan leaders, so you had the top two Democrats and the top two Republicans from the House, and the same went for the Senate. They’d meet once a week.

And then the president had a separate meeting, also once a week, with the Republican leaders. Sen. Everett Dirksen, R-Ill., was in charge of the Senate Republicans at that time, and Rep. Jerry Ford, R-Mich., was in charge of the House Republicans, and they both kept their members in line.

And there was a degree of loyalty back then, that you don’t get in our modern Congress. That’s because members can utilize television and go home every weekend and there is an entirely different discipline structure than there was back in the Nixon era.

TWN: Can we get back to that?

DC: The answer is leadership. And, having a president and leaders in Congress who decide that it is more productive to work with one another, and that that’s what the public wants. Ultimately it’s the public that would be making the demands, because the politicians are going to listen to what their constituents tell them they want.

TWN: Okay, so what was it about the way the Nixon White House worked that people are so drawn to?

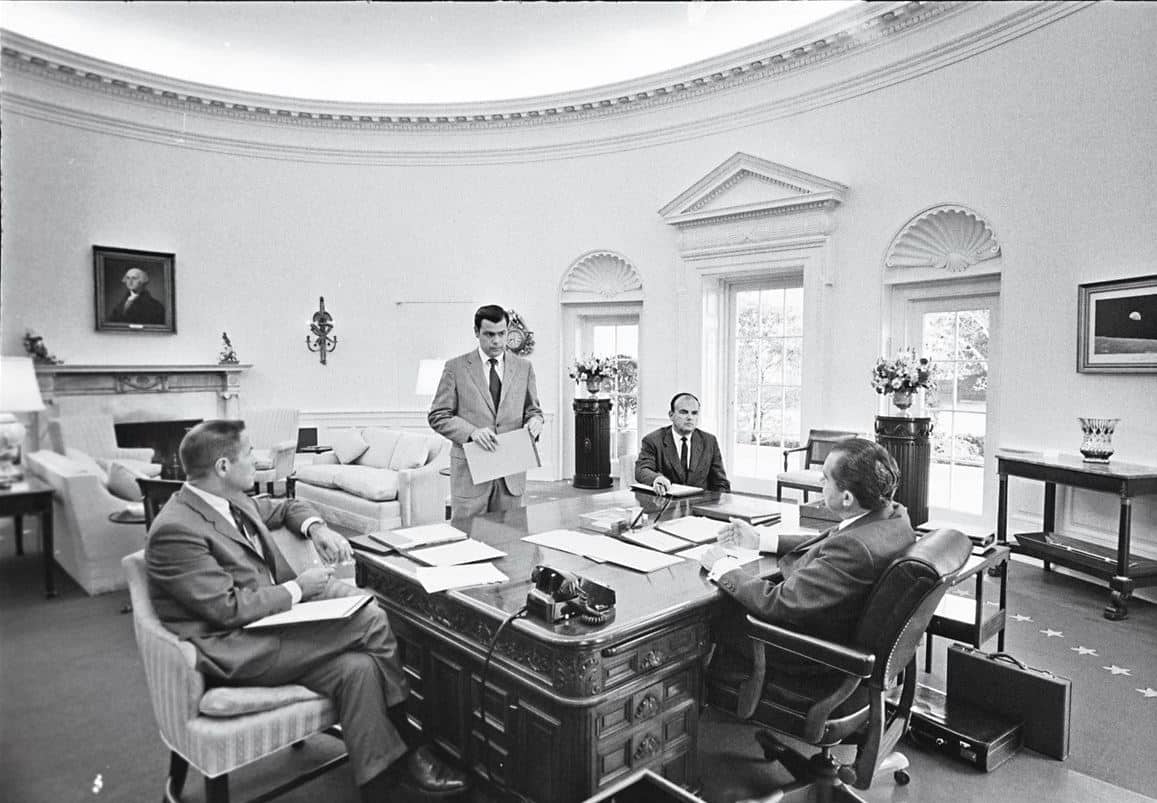

DC: What was put in place was a way of taking and processing a request or a policy change through the White House advisors and various departments. It was called a staff secretary system, and I guess the best way to explain it is to give you an example.

In most situations, you would think that the secretary of Transportation would be requesting a meeting with the president. Under the Haldeman system, the secretary of Transportation would request a meeting and we’d say, “Okay, give us a document that spells out what the meeting is about, what the president is going to be asked, and whatever options you want him to have.”

So now the secretary of Transportation has to think all of that through, then he gives the document to the White House staff secretary system.

I was in charge of meetings, but I couldn’t set a meeting until that document was staffed out to all the domestic council people with the departments that would either implement the proposal or have to deal with whatever decision was being made.

The result is, by the time you have a meeting with the president, you have the views of everybody — in addition to the secretary of Transportation — who also has views on the matter. It could be the secretary of the Treasury, or, if it’s a State Department or Defense issue, they would be asked to offer input.

In short, whoever is affected by what is going to happen, their views are solicited and given to the president, all at the same time, so that there’s no back and forth and no jockeying or trying to lobby the president.

Then the president would look at the document and read all of our opinions and if he felt the meeting was warranted, the meeting would happen.

TWN: It sounds efficient on one hand. On the other, it sounds like it made for very short meetings.

DC: It did. And first of all, Nixon hated meetings. And he said, “I’m just not going to have meetings all day.” And of course, all of the cabinet officers thought that, you know, they ought to be able to go in and have a meeting with the president whenever they wanted to discuss X, Y and Z.

Well, there are not enough hours in the day. There’s just not enough time. So you have to come up with something that says, “Okay, if George Romney, who was secretary of Housing and Urban Development, if he wants to come in, what does he want to talk about? What is he trying to get the president to decide?” And then, “What other people at what other agencies and so forth would be affected by that decision?”

Now, this system takes a lot of work from people around the president. I mean, it took a very strong Domestic Council under John Ehrlichman to be able to pull that together, just like we had a strong National Security Council under Henry Kissinger to pull together the same kind of information whenever an ambassador came in with something from another country.

There’s the request. We want to know, “What is that ambassador coming in for? What is he going to ask of us?” And, “What is the opinion of the State Department, the secretary of Defense … ?” And in a case where the request was monetary, we would want to know what the Treasury secretary thought. And so our system, what Bob put in place, solicited all that information and got it in front of the president. Then he either could decide to make the decision without holding a meeting or he could say, “Okay, now I want to have a meeting, bring them all in and we’ll iron it [out],” particularly if there was something of contention.

It didn’t eliminate the need ever to have a meeting, but many times it prevented a meeting that was largely unnecessary.

TWN: In “The President’s Man” you lay out a very detailed chronology of the Watergate scandal, so I’ll leave it to your readers to experience your blow-by-blow account. I do wonder, however, what it felt like the moment you learned something had happened at the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee, assuming you didn’t know in advance.

DC: I did not. The first I had learned of the break-in itself was later in the morning of June 17, [1972]. The actual break-in had occurred in the early morning hours the same day and I was away at the time on the eastern shore of Maryland.

I got a call from Bob Haldeman, who was in Key Biscayne at the time, asking me if I knew anything about any kind of plan to break into Democratic headquarters. I told him I did not, and at that moment I realized he didn’t know about it either because he found out from a wire service report.

So that was the first clue something had happened, but it still took several weeks before the news stories and everything started building up … and it was October, right before the 1972 election, when my name first surfaced because I had hired a person named Don Segretti to do what we called Dick Tuck-type pranksterism and tricks on the Democratic contenders. [Editor’s note: Dick Tuck, who died in May 2018 at the age of 94, was a Democratic National Committee consultant, strategist and advance man who became legendary as the party’s “prankster-at-large.” Starting in the 1930s, he bedeviled and needled Republican candidates for decades. Nixon, one of the most frequent targets of Tuck’s dirty tricks, was also an ardent admirer. On one White House tape, Nixon can be heard going so far as calling Tuck “a master.”]

Don’s name was in an address book that belonged to E. Howard Hunt, who was one of the main Watergate figures. It was Hunt who organized the break in and he was arrested, along with G. Gordon Liddy and the five burglars at the Watergate.

The address book had been in E. Howard Hunt’s safe and once the FBI found it, they found the name Don Segretti and through him found me. But like you said, I’ve laid this out in the book and one of the nice compliments I’ve received for it is I offer one the simplest explanations and chronology of how Watergate unfolded.

TWN: Well, we’ll leave it then to the interested reader to pick up a copy at their local bookseller. That said, you did do some jail time related to all this, but from what I’ve heard, you’re really very philosophical about it.

DC: What I say is I wish all the amazing experiences I had hadn’t come with a price tag called Watergate. But you know, in a sense I was lucky because my incarceration occurred when I was a young man, it happened early in my life.

I’ve always felt sorry for the men who were older and this [disgrace] was kind of the capstone of their career in public service, and it wound up screwing up the end part of their lives. For me, it gave me knowledge and a breadth of experience that few young men would ever have.

I regret the mistake I did make, but I have a huge, huge amount of gratitude for the gift Nixon gave me, letting me serve him and his administration.

TWN: What do you say to people who say, “You know, if Nixon had only told the truth earlier … things would have been different? If he didn’t engage in the coverup, he would have served out his term.”

DC: What-if is a path that’s hard to follow. I have not tried to live the what-if game. I am much more of a realist. And Nixon himself was a pragmatist.

What happened, happened. Let’s accept what happened. Let’s say that we were wrong, and then let’s reconstruct our lives and move ahead. That is exactly what he did.

I mean that man was taken down, devastated, and actually got incredibly sick for a time, as you may recall. And then what does he do? He starts building himself back up. He goes on national television with David Frost and he apologizes to the American people. He then goes on to write nine books and begins to act as an advisor to other presidents.

And he starts holding dinners at his home in Saddle River, New Jersey, and the elitists and the members of the liberal media who beat his brains out, stand in line hoping to get an invitation because they know the guy is so smart and they want to go listen. I mean, it’s an unbelievable story, the way it all ended up.

TWN: Did you see him after that? Did you attend those dinners?

DC: I did. I saw him many times, and there would also be various reunions or special occasions where we would all be. So I saw him many, many times over the years.

And he was good. He’d made peace with himself. And he loved to have six or eight people over — and always the most interesting people. He had the president of The New York Times over, he had Rupert Murdoch and God knows who else … and they would sit around and talk about issues. And people wanted to be at those events. It was kind of ironic.

TWN: Before I let you go I want to ask you about the situation in Ukraine. Nixon obviously negotiated a test ban treaty with Russia. How do you think he’d handle this crisis today?

DC: Well, I think the first thing Nixon would say is you’ve got to understand the history of the Soviet Union and of Russia, and the imperialistic nature of their thinking. And you also think, okay, if I have to give them an inch, or a mile, at what point can I hold them from thinking they can acquire land and move around the way that they do.

I think right now you have to be asking, what is the strategy with NATO? What is the strategy for all of our allies? What are the pressure points? Are they being applied in a way that’s not a band aid or simply some superficial way to try to head off a spanking. How can we put some steel in it? How is the impact of our restrictions and actions and sanctions going to be verified, so that we know that they work.

And I think the president would summon the top experts on Russia and would consult them and he would be putting a strategy in place … and he would probably do it with an incredible amount of privacy, not trying to orchestrate it through media channels, alerting everybody to what he was thinking. He would be getting it thought through and moving it into action without going with all of the publicity about what we’re trying to accomplish.

TWN: We’re talking just as the U.S. and allies are dramatically ratcheting up sanctions against Russia. Do you think the sanctions are going to work?

DC: If the sanctions have real teeth. I mean the classic example of a blunder in this regard was when President Obama drew a “red line” on what it would take to lead him to use military force in Syria.

He said, “the Assad regime using chemical weapons.” And then all of a sudden there was no red line? Remember that one? What Nixon would have said in an instance like that is, first of all, there’s a question of whether you should ever say what you are going to do publicly. You do it through back channels. You call in the Russian ambassador and ask him to tell Putin whatever it is that you are going to do. And then you make God damn sure you’re going to do what you’ve told the ambassador you’re going to do. You know what I mean?

So on the sanctions, the scuttlebutt and the hype and the back and forth in the media on the sanctions may, in some ways, be undermining the sanctions. I’m not quite saying that the right way, but I imagine you get what I mean.

You have to mean what you say in foreign policy. And that doesn’t mean you’re not flexible … because if you are doing it back channel, you’ve got maneuvering room. The more that you push it out front, the more it will be interpreted as a success or a failure and it will be interpreted instantaneously. That’s just the way the modern media works.

But this has always been a challenge. Remember Nightline and Ted Koppel? Well back, and this is in the Carter years, the Iranians take the hostages at the embassy and Carter is negotiating and suddenly there’s this new show Nightline, built around coverage of the negotiations.

Up to this point, no one knew what was going on in terms of the negotiations, and then all of sudden, you’d see the president or other highly placed staff walking out of the West Wing announcing the latest thing that had been done behind closed doors. Then the Iranians saw that and responded to it and all of a sudden, everything was being done via Nightline and once that happened, it made it much, much harder to do any of the serious kinds of negotiations that would have led to an earlier release of the hostages.

TWN: One could only imagine the impact of a Twitter type platform back then …

DC: You know, I was talking about that the other day. As you know, President Trump really embraced Twitter and it was probably the thing that kept him alive during the first three years of his presidency. He was very successful in getting his message out.

Nixon, of course, didn’t have Twitter, but he used television just as successfully. Back in those days, if the president of the United States said that he needed air time — this was before cable — all of the major networks, very patriotically, would give it to him.

So what you had during Nixon’s presidency was the president going on television seven or eight times, with charts, explaining whatever subject he was talking about. Several of these addresses were about Vietnam, and we went right over the media. He knew that in order to have the support of the American people … he needed to address them directly.

So Nixon used the medium he had, the Oval Office address, very effectively.

Today, the major networks are all about entertainment, and if there’s news, a presidential appearance, they push that stuff to cable. So you only have a fraction of people watching and that makes it much harder to lead in my opinion.

TWN: Back to the Ukraine crisis for a moment. Do you think this can all end with Vladimir Putin still in power?

DC: I do not know.

TWN: One last question, also about power. There’s a feeling, among some, that Republicans are going to have a very good year in the midterms. If they do, which version of the Republican party do you think we’re doing to see. Will we see a return of the more traditional Republican on Capitol Hill or more followers of former Trump? Traditionalists or Trumpies?

DC: I am as anxious as you are to see what unfolds. I have no idea. But Nixon was a party person. And, you know, the party goes through all kinds of ups and downs. It’s the nature of the beast. And somehow, with scotch tape and bailing wire and everything else, they put it together. So we’re just going to have to wait and see.

Dan can be reached at [email protected] and at https://twitter.com/DanMcCue